Defining 'data' for cultural organisation: data horizons 24 Dec 2024 3:04 AM (3 months ago)

In the past couple of weeks, I’ve read and listened to a couple of good things about ‘data’ in the cultural sector – the challenges, opportunities, and what to do about it all.

In doing so, it occurred to me that a term as broad as ‘data’ is only a useful shorthand up to a certain point. You can only get so far before you have to put the brakes on and say ‘wait, what do you mean by that?’

That’s because we use it to cover a huge list of sources, uses, and processes that each have very different considerations. And as soon as you start using absolute terms in reference to abstract nouns it's hard not to think of all the exceptions.

And if that opening sounds familiar then that's because I said the same thing six years ago when talking about 'digital' and I applaud your memory.

What were you reading / listening to, Chris?

I enjoyed David Reece's recent series of articles for Arts Professionals. The first one, What do we mean by being data-driven? contained this quote:

Being truly data-driven requires acknowledging the limitations of data. It’s in these gaps that innovation often occurs. Bold decisions go beyond anything the data can tell us.

I also listened to episode 2 of the Digital Culture Network podcast where James Akers interviewed Ollie Couling, who said:

I think data is the enabler to something. It's not the answer to something. Exploring that idea a little bit, we have all this historic data. It's great. It helps us make decisions. But it shouldn't be the thing that makes the decision. It should be the thing that starts the conversation or creates a hypothesis or that you use to make some assumptions. The assumption making - that kind of hypothesis making - that's the strategy bit.

The data is there to help you shape your decisions and not to tell you what to do. Because, if you think about that logically, if you're only working on data from the past, that's creating its own kind of feedback loop in itself. You need to go out there. You need to think of new things and explore.

(Lightly edited to remove conversational bits. Full transcript on the link above).

None of which is particularly wrong. It's just that the use of 'data' here is way too broad to be able to talk in specifics and I thought I might be able to add some specificity.

Data horizons

So how about this? A simple categorisation that can be applied to different types of data which, looked at over different time periods, lend themselves to different uses.

I've jotted down a few use cases that are specific to the arts and culture sector, but I'm sure you can think of more.

| Horizon | Description | Purpose | Data Velocity | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate | Real-time views and automations | Instant action | High | Personalised website content and timely comms |

| Short | Reactive analytics | Rapid response | High | Monitoring and automatic optimisation of live campaigns |

| Medium | Operational optimisation | Process improvement | Medium | Post-campaign reviews, content planning, audience segmentation |

| Mid-to-long | Predictive analytics | Anticipate trends | Low-Medium | Forecasting attendance and allocating marketing resources |

| Long | Strategic insights | Guiding longer-term strategies | Low | Multi-year audience engagement/programming strategy |

| Furthest | Historical analysis | Context and evaluation | Static | Evaluation of arts programs |

(Apologies if that table doesn't work too well for you on a mobile device).

In case you're thinking about it, I did consider putting examples of data sources against each horizon but realised that's not feasible. The same data can be viewed differently on different timescales and combined in various ways for various outcomes.

Applying the data horizons

With everything laid out, perhaps you can see why I'm uncomfortable with absolute statements to the effect that 'data shouldn't make decisions for you'.

Sometimes it can and should. Sometimes it can't and shouldn't. Some types of data lend themselves to that kind of use and some don't.

There's a spectrum that runs through various points including:

- automated by data

- data-driven

- data-informed

- sod the data, we're doing it anyway

To take a very specific example, at the 'Immediate' horizon, you would want to set up proper data collection (of page views and conversions) so that it can drive the automatic optimisation of your Meta Ads campaigns.

Other data might automate whether you try to upsell a ticket buyer to a membership or send someone a post-show email.

Because there are specific use cases, this is where you'll find off-the-shelf tools to do the job for you. As the horizons get more distant data can become less specifically actionable and is more likely to be one of many inputs needed to make decision or form a hypothesis.

In this context, the points made by David and Ollie make the most sense when looked at through the lens of the 'Long' horizon where the aim is to identify strategic insights.

Even then, I'd stick up for data somewhat. Dismissing data as secondary risks reducing strategy to guesswork disguised as creativity.

Data (in the form of market trends, performance metrics, benchmarking, and customer preferences) can be just as valuable an input to a strategic vision as organisational capabilities, macro-environmental factors, competitive intelligence, and gut feel. Data vs creativity is a false binary.

One last thing for now. I like Ollie's point that:

if you're only working on data from the past, that's creating its own kind of feedback loop in itself.

…and I've certainly seen 'strategies' that amount to little more than post-rationalising existing activity, with targets that are barely incremental rather than (as you'd usually hope) potentially transformational.

However, at other data horizons, feedback loops are brilliant and necessary. When you're getting into the execution of a strategy, that sort of iterative learning is needed so that the approach, and the strategy itself, can be refined over time.

I think there's more to say on this topic, and maybe spelling out the various types of data would be a useful companion piece to this. But I've not been writing much on this blog recently so one step at a time.

Obstacles to developing digital-centric business models in the arts 16 Sep 2020 2:56 PM (4 years ago)

The other day I was asked how the coronavirus pandemic has impacted the business models of UK performing arts organisations.

More specifically (because obvious answer is obvious), has there been an increase in the number of digital initiatives, or have there been other important implications?

I sent back the answer below. It’s not a complete answer, and I was possibly being a bit pessimistic. Still, I thought I may as well put it here.

Here’s what I said…

There’s certainly been an increase in digital initiatives, some better thought through than others, but this comes with all sorts of caveats.

a) A lot of digital activity has been driven by an idea of public service, rather than as a way to generate income. There are some exceptions – but I don’t think any venue-based organisations are succeeding online to such a degree that they’ll want to go 100% digital from this point on. I also think there’s some evidence that the public-serving missions of arts organisations can be an obstacle to fully exploiting revenue-raising possibilities (and whether this is a good or bad thing will be a question of degree and individual philosophy).

b) Performing arts organisations have furloughed, reduced working hours, or made redundant large swathes of staff, meaning that in many cases i) there are fewer people around to work on new solutions proactively, and ii) those remaining are over-worked just trying to maintain buildings and a small level of activity, with little scope for exploiting new avenues.

c) There’s a well-documented lack of digital skills within many organisations, which may mean that opportunities aren’t executed as well as they could be, or aren’t grasped by executive teams and boards in the first place. Add to this that there’s not a lot of funding about for R&D and solutions are needed now – not 12 months down the line.

d) With the financial outlook looking bleak for some time yet, few organisations are looking to place bets on new strands of activity that might not pay off. I know of several who aren’t able to sign off on work by agencies unless there will very definitely be a positive financial return.

e) I think (too?) many organisations are thinking about how they generate activity for their existing audiences (with the aim of keeping top of mind until they can welcome them back into venues), and are failing to think about how they could/should be collaborating with others and developing cross-organisational platforms for presenting work. We’re starting to see some interesting exceptions, but not many. And compare this to companies in the commercial sector who have had to pivot a lot more urgently to stay in business.

(Photo by Masaaki Komori on Unsplash)

Actually yes, people do want virtual museum tours 7 May 2020 12:27 AM (4 years ago)

UPDATE: this was written in July 2020. As of December 2024, people aren't searching for this stuff anywhere near as much.

Short version: Contrary to what you might have been told, lots of people are still searching online for virtual museums.

Also, be careful with Google Trends data, don’t believe every smartly written headline you see, and be aware of confirmation bias.

The longer version is that an article has been doing the rounds since 30 April titled People Don’t Want Virtual Museum Tours; Do This Instead.

It’s very forthright, has a grabby title, and has been shared and commented on uncritically by a lot of people (certainly more than are going to share this one).

When I first started reading it I was really interested – there’s a lot of learning to be done right now about what people are looking for online, and this sort of thing is right up my street. But as I read on, well…

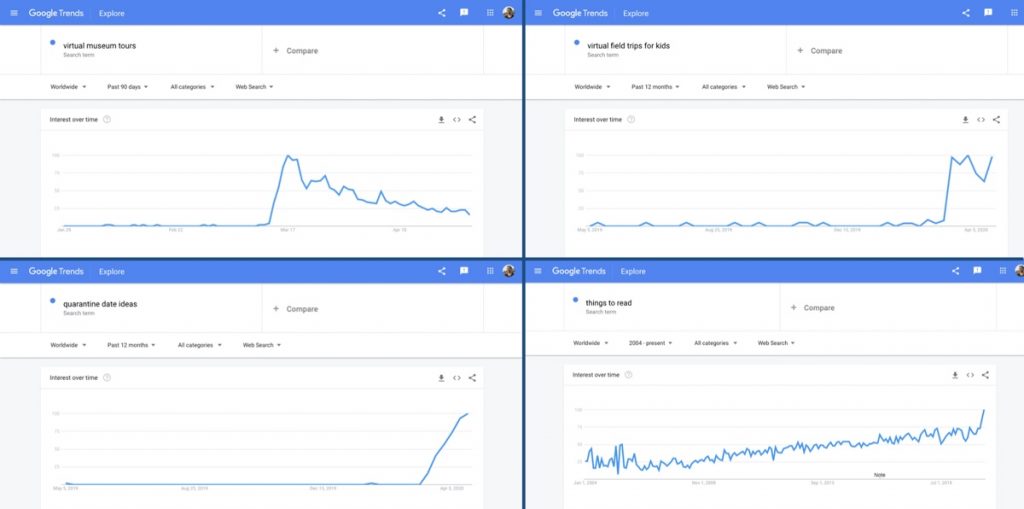

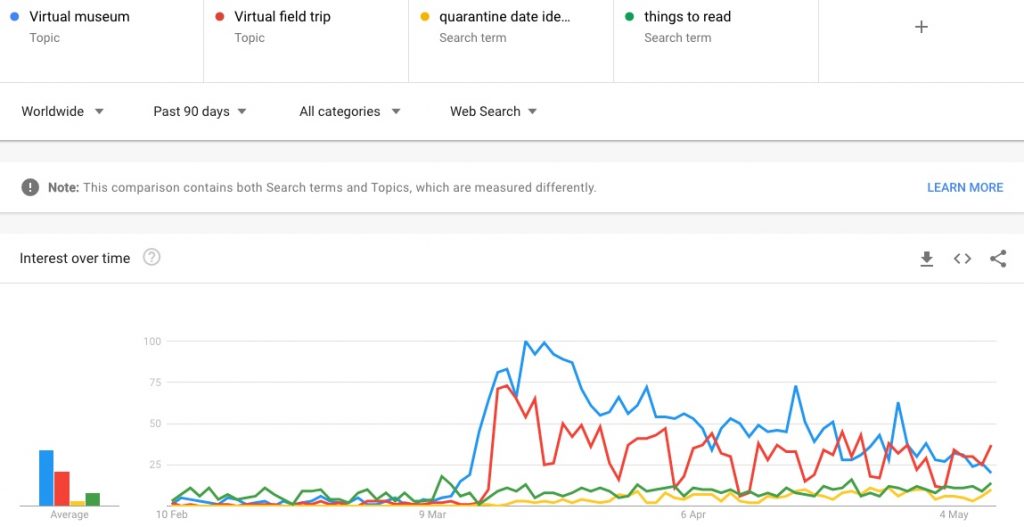

Here’s the gist of what it’s saying. While there was a big uptick in searches for virtual museum tours a few weeks back, that interest has peaked, is sharply declining, and instead the following searches are now ‘surging’:

- virtual field trips for kids

- quarantine date ideas

- things to read

The article evidences this with charts from Google Trends showing that those search terms are now more popular than they’ve ever been.

Here they are. If you were picking a winner, which would you absolutely not pick?

Exactly, you’d tell everyone to steer clear of the one in the top left.

But those charts would also give you entirely the wrong idea about what’s happening.

All they’re doing is showing you when those terms were at their most popular over the past year. Not how popular they are overall, or in comparison to each other.

Comparing the search terms

Google Trends is only useful for relative comparisons – comparing search terms to their own past performance, and against the performance of other terms. Frustratingly, the article actually explains this critical point and then ignores it.

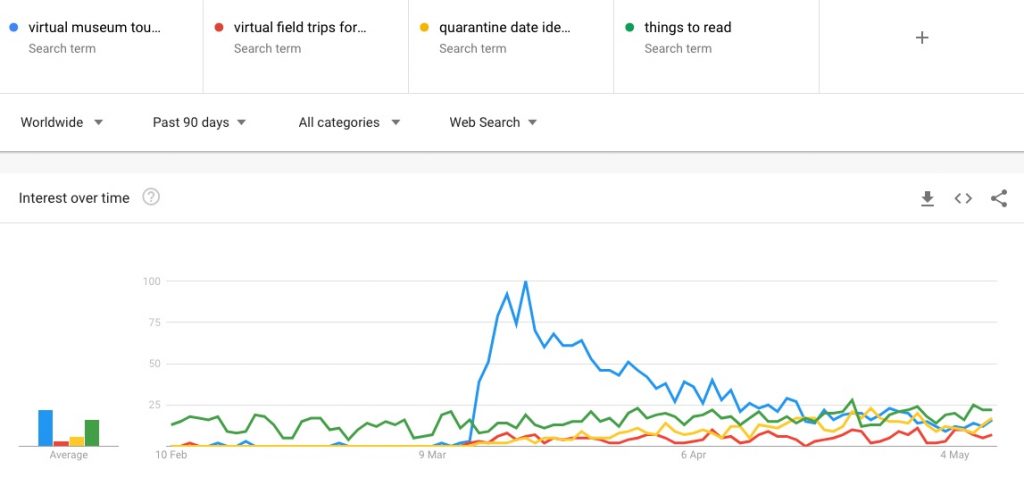

Let’s see what happens when we get Google Trends to overlay the four charts…

That’s a very different picture (sidenote: all my screenshots are as at 8 May – click the images for the latest data).

Sure, interest in ‘virtual museum tours’ exploded early on and has tailed off since, but it’s still way up from what it was, and only the incredibly generic ‘things to read’ is beating it. That may change at some point, but I wouldn’t say those other terms are exactly ‘surging’ right now.

That’s not the whole story though.

Better terms and even better topics

The next thing to fix is the choice of search terms. We nearly miss out on some very interesting insights with the ones we’re currently labouring with.

In the four original charts, Google Trends is being asked to show ‘search terms’. That means it’ll return the relative popularity of those exact words.

In which case:

- Why specify virtual museum tours? Isn’t ‘virtual museum’ specific enough?

- Who searches for virtual field trips for kids? Aren’t they all for kids?

We’re looking for broad trends here. If we focus on search terms that are too specific then we risk missing out on higher volume searches and the bigger picture.

Again, frustratingly, the article points out that “to a degree you still need to pinpoint an accurate search” but does nothing to solve for it.

If we tweak those two search terms the chart changes in a really interesting way.

We can immediately see that ‘virtual field trips’ is a much more popular term and has a very different pattern to it. It’s gone from trailing along the bottom of the chart to almost (but not quite) reaching ‘virtual museum’ levels of interest.

We can also see that it spiked early on and has been declining week on week ever since. Just like ‘virtual museum’.

But overall, we see that ‘virtual museum’ has been, and still is, a more popular term than any of the others (save for a brief moment on 7 May).

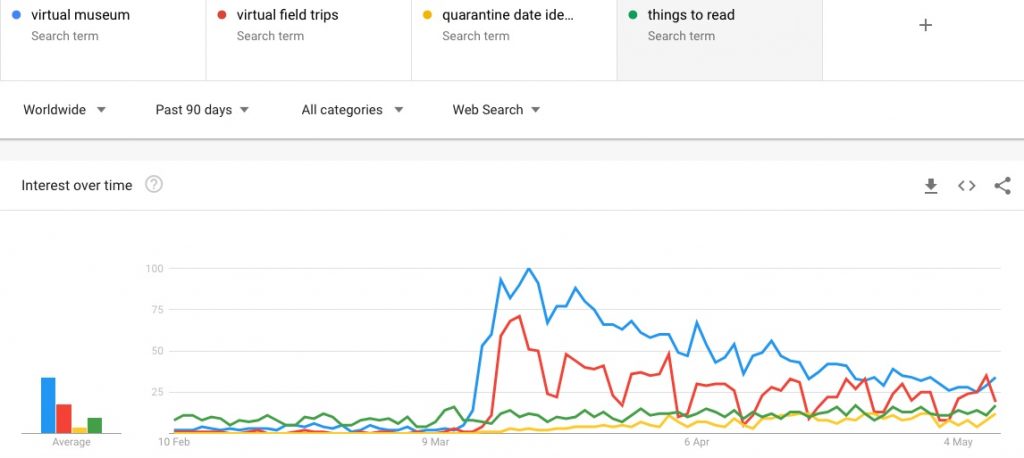

There’s another improvement we can make.

Picking the right search terms in Google Trends can be a pain. Sometimes there isn’t a single term that’s applicable and we want to group together different variations – singular, plural, and modifiers like ‘near me’ or ‘for kids’.

Language is an issue too. These charts have the location set to ‘worldwide’. I’m guessing not many people in Spain or India are likely to type ‘virtual museum tours’ in English (in fact, why guess?).

Happily, we can use ‘topics’ in Google Trends to group together terms that share the same concept in any language. So let’s do that (sadly there aren’t topics for ‘quarantine date ideas’ or ‘things to read’).

There we go. We can see that ‘virtual museum’ and ‘virtual field trip’ both surged in popularity and have both declined, while still being relatively much more popular than they were before mid-March.

Would we conclude from this data that people aren’t interested in virtual museums? Or virtual field trips? Of course not.

Do people want virtual museum tours?

Yes. They’re still showing interest in the concept. For now.

Is interest growing in other terms like virtual field trips for kids, quarantine date ideas, and things to read? Not really. That doesn’t mean there’s not some interest there, but I wouldn’t bet the viability of my organisation on those particular terms.

Does everyone want to visit virtual museums? Of course not. Are they the only things people want? Don’t be daft. Why are people in the museum sector so keen on giving the concept of virtual museums a kicking? Don’t get me started.

To be absolutely fair, Museum Hack posted something of a clarification/row back…

also, maybe worth noting that "virtual museum tours" still has meaningful search volume that may extend to end of pandemic and beyond, its just on strong downward trend. thanks for including us ☀️

— Museum Hack (@MuseumHack) May 4, 2020

But nuance doesn’t get your article shared by hundreds of people who don’t think for themselves. Actually, that’s unfair – neither of us has a particular interest in torturing this data until it tells us what we want.

I should also mention that I quite like what Museum Hack are doing generally and, as much as the article irked me, I’ve only really written this because of the reaction to it.

Why not both?

Of course, contrary to the title of the original article, none of these things are mutually exclusive. With time and resource, there’s no reason you couldn’t do all of these:

- Create some form of virtual museum tour

- Package up experiences as virtual field trips for schools. Bear in mind that ‘field trips’ is a more generic term and that’ll mean more competition

- Write a blog post on quarantine date ideas that use your museum, objects, or subject matter as inspiration, AND

- Publish a list of top things to read, linking back to your old posts, cross-linking to other institutions/publications, and highlighting books in your shop

Some of these things are going to be more in keeping with what a museum’s audience might expect from them. Some might be more suited to being offered by a tour company.

Although, if you didn’t have the assets and processes ready to go pre-lockdown, then items 1 and 2 might be tricky. Perhaps 3 and 4 are more easily doable.

Sidenote: it’s no huge surprise that the organisations that’ve been taking digital activity seriously over the past few years are the ones who’ve been better able to adapt to the current situation.

I would also drop in a couple of caveats…

You should be informed by this data, not driven by it. Let’s not forget that the data we’re looking at here is what the worldwide population are typing in to Google:

- Just because people aren’t actively searching for something, doesn’t mean that they won’t want it (search isn’t a channel for discovering new things)

- If people are searching for these things then unless your content is showing up near the top of Google’s search results you won’t get much of a bump in your website traffic, and

- To the extent that the data shows what people are interested in generally (and that you can present to them through channels other than search engines), bear in mind that your audiences may not reflect the worldwide population

What else do people want?

Right now, who really knows? But I’m guessing it’s the same things they’ve always sought out. Expertise, distraction, connection, things to do, familiar things, new discoveries, a nice setting for some other activity, something to show off…

Some of those might be solved by a virtual tour of a museum, or some inventive homebound date ideas, but some won’t.

I suspect lots of people would actually quite like to visit museums but are settling for the next best thing.

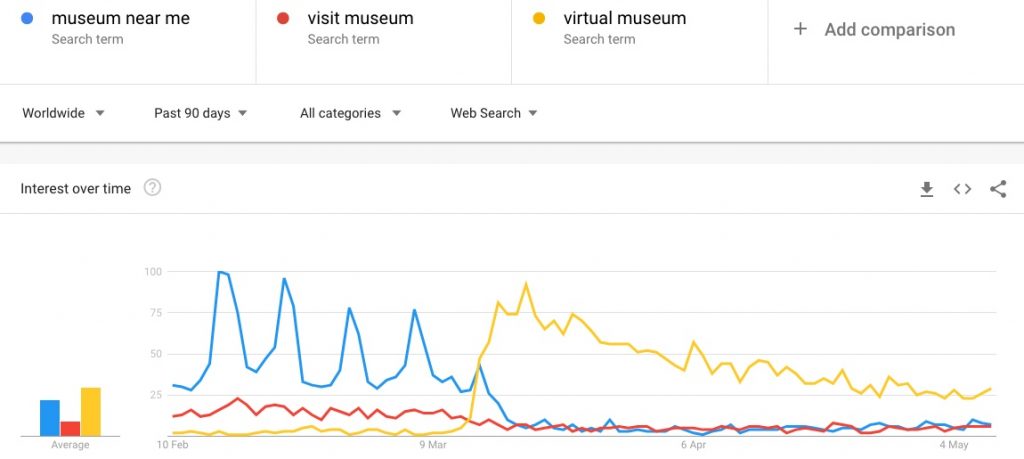

I’ll end with one last chart.

One interpretation (and we do have to be careful with this type of data) would be that people with some sort of propensity for visiting virtual museums are as interested in visiting virtual ones as they were in visiting actual ones.

In which case, rather than dismiss that interest, we should think about how best to respond to that interest, welcome people in, and make them want to tell others about their great experience.

(Photo by Andrea Ang on Unsplash)

Questions about the cultural sector's pivot to digital 19 Apr 2020 8:46 AM (4 years ago)

I’ve been wanting to write something about the digital aspects of how cultural organisations have reacted to the shutdown, but…

Well, firstly, there’s just too much going on. Every ‘what if…’ thought experiment from the past twenty years is currently playing out allatonce. There’s been a flood of helpful and not so helpful prognostications (sometimes they’re one and the same think piece), and I’m wary of adding to the wrong side of that pile.

Plus I have got a toddler, a business, and a personal life to keep up with.

And anyway, in complicated situations you want to be sure that you’re asking the right questions. So here are some that have been pinging around my brain the past few weeks. Answers to some of them are forming, but I’ll try to keep those out of this for now.

Here we go…

1. With furloughs, layoffs and restricted activity kicking in at cultural orgs, what constitutes an effective skeleton crew when visitors/audiences can (temporarily?) only access them digitally? Or is the cash from the job retention scheme more important than all of that in the very short term?

2. When will more cultural organisations start collaborating (with each other, their communities, or across other sectors) whether formally or informally, rather than competing for attention in an increasingly flooded market? Interesting to see that Manchester and Bristol are ahead of the pack on this.

3. Despite early hopes for the internet being a federated or distributed system, people have tended to congregate around a few key platforms and providers. Will consolidation happen and, if so, in what areas? For instance, there might be room for an orchestra in every city, but when geography is less of an issue, then what happens? What does that mean for smaller orgs?

4. Unbundling has been another key element (think of the revenue-earning bits of local news being picked off by property websites, online classifieds, dating apps, etc). How’s that going to come into it? I’ve never thought it made much sense for hundreds of cultural organisations to toil away on their own rarely-visited educational resources.

5. Is the rush to release free content going to turn out to be a bad idea? After all, it’s generally accepted that discounting tickets should only ever be done with a very specific aim in mind. For what it’s worth, this is the one that I have the most opinions on. The answer is obviously ’it depends’ but within some reasonably knowable criteria.

6. To date, very little digital programming by cultural orgs has been expected to contribute directly to earned revenue (it usually gets a pass as innovation, marketing, or is funded in some way). I’ve long suspected this is why it’s not taken particularly seriously and tends to be a bit flabby. With a lack of business model, is a rush to do more of this stuff going to be a drain on organisations that can no longer subsidise it through other activity?

7. Is the requirement to have an easily deployable ‘shutdown mode’ going to become a standard feature of website briefs?

8. What are the new (or existing but underserved) attention patterns that organisations can/should adapt to? Fewer people are commuting, and nobody has to rush for the last train home. So for live events, what are the good times for communal activities?

9. Similarly, you can play/take liberties with an audience’s attention when they’ve paid money, come to your building, are sat in a dark room, and social pressure is preventing them from getting their phone out. When they’re sat at home on their laptop or mobiles with work, children, or Candy Crush vying for their time, how’s that 4.5 hour performance looking then?

10. Art has often/always been shaped by its canvas (or played against it). What are the emerging formats? Which existing ones translate well digitally, and which don’t? Put another way, if people can’t come to an exhibition, would it still make sense to put paintings on the walls of a gallery and then walk around filming them? What achieves the ‘point’ of an exhibition (insert other analogue presentational format) but uses the affordances of digital media?

11. People complain about live performance not translating to digital (ie screen) media very well. But why is that usually framed as being the fault of digital media, rather than the inability of the thing to adapt from one space to another? I’ll answer this one quickly, because it’s not a particularly new question. The only real faults here are in the facile criticism, and a lack of imagination used when translating something from one setting to another.

12. Again, not a new question, but have some artforms become over-specialised to the extent that they can only thrive in certain conditions (high capacity venues, corporate support, and tonnes of public funding)? Have they been encouraged to become giant pandas (which, don’t get me wrong, I’m a fan of) when it’s the foxes that’ll thrive right now?

13. For a simple rule of thumb to use as a guide to which organisations are likely to thrive and which are more struggle, how about seeing how many people in positions of influence are aware and open to digital possibilities, versus those who complain that it’s not the same as the ‘real’ thing?

14. More of a comment than a question (ugh), but this could’ve been consumer VR’s moment.

And the ones that I’m really interested in…

15. Which cultural organisations are going to come out of this situation well? What are their characteristics? What have they been doing over the past few years? What are they doing now? Who are the people responsible for leading and executing on their plans? Were they hired in or trained up?

16. If/when things return to ’normal’ how many organisations will carry on with some/all of what they’ve been doing over the past few weeks?

17. Will that happen before organisations are really forced to consider longer term changes in order to stay operational? And what does ‘operational’ look like then?

Maybe one day I’ll get the time to write some thoughts down on some of these.

(Photo by Clint Patterson on Unsplash)

Update: I had a chat with Ash Mann on the Digital Works podcast about some of the questions above.

The what, why and how of Cultural Digital: Streams 2 Apr 2020 1:33 AM (4 years ago)

I’ve put together a simple website at streams.culturaldigital.com to list lots of the performances, classes, and more that are being put online by cultural organisations while they’re closed.

Here’s a bit of info about the what it is, why I put it together, and how.

What

By 25 March, many cultural organisations had been closed a week or so and an increasing number of them had started to release recordings of performances online.

I gave up a lunch hour to put together a Google Sheet with links to lots of these streams.

I already use the name Cultural Digital for a couple of disparate projects – the email newsletter, The Library – so that seemed like a good home for this thing.

So I created a page at culturaldigital.com/streams and added a Google Form for people to submit anything they’d seen. Then I tweeted about it.

It's brilliant that arts and culture organisations are making so much available digitally, but it's getting overwhelming so I've started putting this together: https://t.co/dMnSXCbvZ7

— Chris Unitt (@ChrisUnitt) March 25, 2020

Please fill it up with links to performances, tours, talks, classes, games, etc

That process took me just over an hour.

Over the following week I added more to it. People shared it around. Other listings appeared, some also using Google Sheets (shout out to National Dance Company Wales and the very good one by Alisa Kalyanova).

I spent a bit of time each day adding more info as and when I came across things, or when people submitted it. Someone got in touch asking if I wanted to turn it into a more robust thing, but I’d already been thinking about doing that myself.

On 1 April I got up early and created streams.culturaldigital.com. Then I tweeted about it (twice, because I used the wrong URL the first time).

I've turned my spreadsheet of streaming arts performances/classes/etc into a website https://t.co/7mOEkDlitV

— Chris Unitt (@ChrisUnitt) April 1, 2020

Still a work in progress. Suggestions and links welcome! pic.twitter.com/lz6IolBCqk

Why

With the current lockdown and the closure of theatres and concert venues, lots of performing arts organisations have started streaming recordings from their archives.

Some things are only available for a short period of time, some are live and if you miss them they’re gone. And there’s been a lot. It quickly became impossible to keep up with everything.

This isn’t really a new problem. It’s just an old problem that’s recently got bigger.

Cultural organisations have been dipping various toes in livestreams over the past few years. Finding out about them has always been harder than it could/should be.

Everyone tends to use their own websites, Facebook pages, or YouTube accounts, so everything is very dispersed. And it’s not like there are listings in the same way as there are for TV or theatre. So there’s a piece of infrastructure missing there.

There’s also some more thought needed around audience development, partnerships, and business models. But one thing at a time, right?

Anyway, as far as this particular infrastructure piece is concerned, it’s something I could contribute to and the current situation gave me a kick to do something about it.

How

The technical part of this isn’t all too difficult. The tools used were:

- Google Sheets to act as a very simple database

- Google Forms to collect data from helpful souls who want to contribute

- Sheet2Site to turn the spreadsheet into a website (I had to pay a small amount for this)

I looked at a few other things for this. I know WordPress a little, but that was way too big and clunky for this and I couldn’t find a suitable theme to get things off the ground nice and quickly. Plus I’d rather edit data in a spreadsheet than I have to treat everything as a post.

I also looked at things like Airtable and a few of the other no-code development platforms out there. Those are great for slinging together a quick minimum viable product, but Sheet2Site was easily the best fit for my project and came with a layout that closely matched what I had in mind.

So that’s the technical side of the ‘how’. But the process side is as/more important.

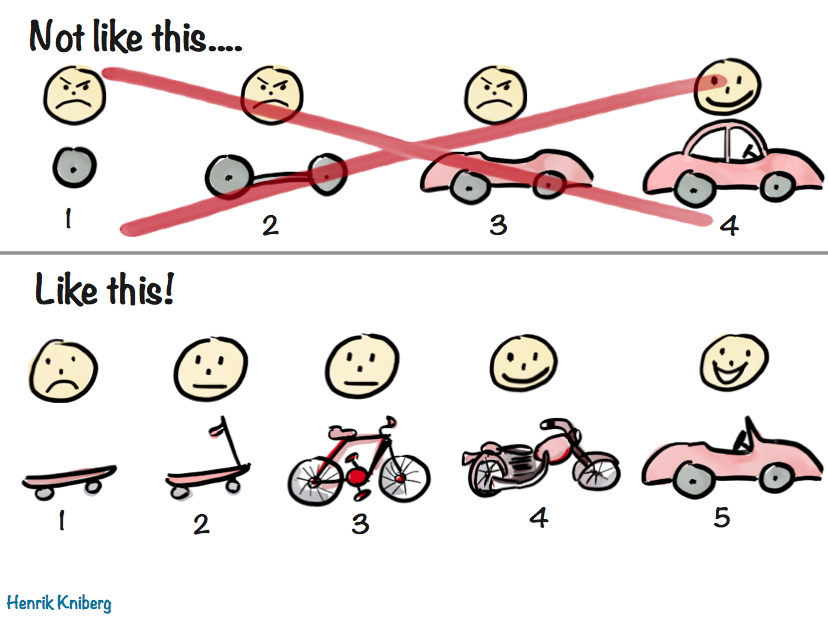

The approach I’ve used is usually called lean or agile. You have a goal in mind – in my case a publicly accessible list of info about and links to online cultural stuff – and you release something that starts delivering value as soon as you can.

You then improve on it bit by bit if you get feedback suggesting that would be worthwhile.

At the other end of the spectrum you write a brief, assemble a team, and spend weeks or months coming out with something that’s beautifully crafted. That approach is called waterfall. There’s nothing inherently wrong about it, but different approaches will be appropriate in different cases.

An agile development process for CD: Streams might look like this:

- Release 1 – a publicly accessible Google Sheet with a Form attached so people can submit their listings. Then gauge the reaction and usage to see if it’s worth moving to the next level. I also built the spreadsheet so it might work like a database, compromising usability a bit, but meaning that the next step might be easier

- Release 2 – a very simple front-end on top of the Google Sheet, with an improved layout and better options for filtering

- Release 3 – more audience-focused functionality. Perhaps better styling, layout and filters (now we should have some data about usage). Maybe an email sign-up and/or reminders/calendar integration

- Release 4 – options for organisations to claim their listings and have dedicated organisation pages. At this stage maybe we hit the limits of what can be done with Sheet2Site and we need to totally rebuild it

- Release 5 – who knows? Maybe dedicated pages for each event, finding a way to integrate content from some of the bigger content platforms, advertising options, listing on the London Stock Exchange…

With each release you look at whether the response justifies planning another release. Are people coming to the site? Are people linking to it? Are people submitting info about livestreams? Are people using the functionality?

Henrik Kniberg’s 2016 blog post Making sense of MVP (Minimum Viable Product) – and why I prefer Earliest Testable/Usable/Lovable explains this really well and uses this diagram to explain the two approaches.

As things currently stand, I reckon that CD: Streams is currently somewhere between a scooter and a bicycle.

It’s delivering value and achieving the goal. It’s just that it could be doing it better. I look at the site and see so many things that are wrong. For starters:

- The filters can be confusing

- Accessibility needs improving

- There’s no way of getting reminders or notifications

- There’s a good list of events but it’s not comprehensive and the metadata probably needs a bit more thought

- The submission form is over-complicated

- The data wrangling behind the scenes could be better automated

Maybe I’ll get the chance to fix some these things (in the midst of coping with a pandemic, looking after a child, and keeping a business afloat) and maybe I won’t. I just have to tell myself it’s fine for now and that everything’s a work in progress.

So here’s Cultural Digital: Streams. I hope you find it useful.

Future-proofing websites 9 Oct 2019 3:16 PM (5 years ago)

A recent tweet asked…

Almost every website brief we receive has a section titled ‘Future proofing’.

— Cog Design (@cog_design) September 30, 2019

What do other people put in that section? How can a website be future proofed?

The short answer

Use widely accepted web standards and a well-supported CMS. Make content and layouts editable as much as possible/reasonable. Design for responsiveness and accessibility, use worst case scenarios where content is concerned, and allow for graceful degradation. Adopt a sensible information architecture. Go for loose coupling of any third party services so others can be swapped in. Plan for horizontal scaling. Make the client own relationships with critical third party providers (hosting, domains, ESP, analytics, etc). Have plans for downtime, backups, and security patching. Put processes in place for ongoing testing, review, and improvement.

The long answer

I occasionally help people write website briefs. I used to write responses to them too. So I’ve come across this question a few times myself.

The first time round, my reaction was probably along the lines of ‘Well, if I knew how the web was going to change over the next few years then I wouldn’t be doing this job’.

There’s also a temptation to read this sort of question as a coded message meaning “We want this website to last 5-8 years with minimal ongoing spend. How can you make that happen?”.

Which is fair enough really (to some extent). You want to spend your budget on new features, not frantically trying to tread water with a core website that hasn’t been built to last.

And besides, future-proofing is common sense in plenty of other areas.

A quick comparison…

Expansion joints, like the one above, are used in large structures like buildings, bridges, and railway tracks. They allow concrete and steel to flex in response to changes in heat, pressure, and seismic activity.

When you’re building a bridge (I assume) you have to answer questions like…

- are we putting this thing in the right place?

- what sort of traffic volume does it have to bear now and how might that change in the future?

- how will the materials involved behave under a range of likely conditions?

That’s not too dissimilar to the considerations that go into building a website. And a website is a heck of a lot easier to tweak than a bridge.

What might change?

Some changes will be instigated from within an organisation, and others will be imposed by outside circumstances. Here are some examples of each…

Internal changes:

- The core offering or new activities

- Branding/design

- Content

- Integration of new or alternative 3rd party platforms

- Who they choose to be their web agency

External changes:

- Changing expectations of users

- The demands of funders

- New legal requirements

- Increasing proliferation of devices people use to access the website

- Significant changes in the number of people accessing the website

Some of these changes are more likely than others, and some are easier to absorb than others. In some cases, a bit of foresight may go a long way towards making change easier and cheaper to deal with, but significant additional work will be unavoidable.

A good web design agency will know from experience where flexibility will be needed, and will be able to anticipate additional changes that might come along. Many will take account of these without thinking of it as ‘future-proofing’.

As for what steps will go towards mitigating the effects of these changes, I refer back the Short Answer above.

Maybe the phrase ‘future-proofing’ is loaded with connotations of gazing into crystal balls. Maybe ‘adaptability’ would be a better way of putting it.

A list of cultural / digital development programmes 20 May 2019 6:48 AM (5 years ago)

Over the years there have been all sorts of publicly funded programmes aimed at getting cultural organisations to do more/better digital stuff.

Details of many of these programmes are fading away, with domain names lapsing and pages being culled as part of website redesigns. So, for posterity, here’s a list of some of them.

If you know of anything that’d be worth adding then please let me know, either via the contact form, or via Twitter.

I’m interested hearing about programmes that involved some degree of intervention – such as commissioning, mentoring, residencies… you’ll get a feel for the sort of thing I’m talking about from the list below.

In the UK

1999 NOF-digitise (New Opportunities Fund)

nationwide digitisation programme, provided funding to make learning materials available, free of charge, on the Internet.

There’s a JISC email list too.

2000-2007 Culture Online (DCMS)

a pilot initiative set up by the DCMS to commission online content

2006 Melt digital content programme, Sheffield

2008-2011 Digital Content Development Programme, ACE West Midlands

a three year programme of investment which aims to catalyse the creation and creative use of digital content platforms for arts organisations across the West Midlands region.

The key emphases of the programme are on an audience- centred approach and on the creation of sustainable content platforms that will continue to be programmed after the end of DCD support.

2008-2010 Media Sandbox (iShed/Pervasive Media Studio/Watershed)

2009 Amb:IT:ion Scotland (Culture Sparks and Rudman Consulting, funded by The Scottish Arts Council)

a new £800,000 programme to support digital development and change in arts organisations throughout Scotland. This flexible and innovative new programme aims to help achieve sustainable organisational change and improve capacity for audience engagement, through implementing integrated IT and digital development.

2009 F2 Digital Creative Development Programme (ICE Coventry)

a 6 month project for established creative professionals who want to investigate the opportunities offered by digital media, form new collaborative partnerships and develop new ideas.

2010-onwards Let’s Get Real (Culture24)

Our collaborative action research programme supports arts and heritage people and organisations to become more relevant, resilient and responsive to digital cultural changes.

2010 Theatre Sandbox (iShed/Pervasive Media Studio/Watershed)

an annual development scheme which supports practitioners from across the UK to develop new work using digital technologies.

2011 Building Digital Capacity for the Arts (Arts Council England and BBC Academy)

a series of practical seminars and workshops, a BBC online guide to commissioning audio visual content, 12 facilitated masterclasses and an online resource of filmed and streamed content

2011 Happenstance (Caper, supported by the Digital R&D Fund for Arts and Culture)

Happenstance puts creative technologists in deep immersion residencies in arts organisations. The Happenstance residencies are designed to change arts organisations’ relationship with digital technology. The residencies are at Site Gallery in Sheffield, Lighthouse, and Spike Island in Bristol.

2012 IC Tomorrow challenge (Technology Strategy Board)

The contest is offering up to ten businesses a maximum of £24K and the opportunity to work with a selection of museums and art galleries to develop prototypes of applications or services.

2012 Sync, Scotland

Sync is a set of activities designed to support cultural organisations in Scotland develop a more progressive relationship with technology and technologists. It has three central elements: the annual Culture Hack Scotland event, a Geeks-in-Residence programme and the Sync Tank magazine. It is part of Creative Scotland’s Cultural Economy programme for 2012-14

2012-15 Digital RnD Fund for the Arts (Nesta, Arts Council England, AHRC)

supported ideas that use digital technology to build new business models and enhance audience reach for organisations with arts projects.

2013-2015 Digital R&D Fund for the Arts in Waless (PDF) (Arts Council of Wales, AHRC, and Nesta)

to enable the use of digital technologies in the arts sector to engage audiences in new ways and to create opportunities for new business models […] provided up to £400,000 in total to arts and cultural organisations

2015 Digital Innovation Fund for the Arts in Wales

Through a combination of funded projects and curated events and information, we look at how digital technology can spark new ideas or shape pathways that can help move arts and culture forward and keep it smart and sustainable. We’re also exploring how we can embed a culture of digital research and development across all levels of arts organisations’ work.

2015-2018 Canvas (Arts Council England)

Its purpose was to provide an online showcase destination for arts video content whilst also supporting arts organisations to develop their capacity to produce high quality video content that was relevant to online audiences.

2016 Digital Arts and Culture Accelerator (Nesta, Arts Council England)

This is a pilot programme to explore whether a tech accelerator model can transfer into the arts and cultural sector, to support innovative new ideas from organisations that do not ordinarily take on commercial or social investment.

2018 Immersive Experiences (AHRC Creative Economy and EPSRC)

supports the development of early-stage research partnerships that will explore the creation of new immersive experiences addressing three key themes: Memory, Place and Performance.

Ongoing Audience of the Future (UKRI)

Those funded through the challenge will adopt, exploit and develop immersive technologies to create new products and services. They will capture the world’s attention and grow the UK’s leading market position in creative content.

Includes:

- Immersive technology investment accelerator

- Demonstrator programme

- Design Foundations

- Production innovation for immersive content

- National Centre of Excellence for Immersive Storytelling

Ongoing Digital Lab (Arts Marketing Association)

The Digital Lab transforms digital practice through intensive mentoring, workshops, and peer support – all taking place online. Fellows are matched with an international specialist who mentors their work-based experiments, supporting an agile approach to their online presence.

Ongoing The Space

We provide commissioning support for arts and cultural organisations, and the artists they work with, plus training events and online resources.

Ongoing Creative XR (Digital Catapult and Arts Council England).

Focused on the creative industries, particularly the arts and culture sector; the programme gives the best creative teams the opportunity to develop concepts and prototypes of immersive content (virtual, augmented and mixed reality).

In the USA

open call for ideas to explore digitally-driven approaches that galleries, museums, performing arts centers, theaters, and arts organizations of all genres might use to inspire audiences.

Ongoing Bloomberg Connects

supporting the development of state-of-the-art technology, from mobile applications to immersive galleries and other dynamic tools, designed to transform the visitor experience, encouraging interaction and exploration of cultural institutions on and offsite.

With thanks to Martin Black, Devon Smith, and Charles Beckett for suggestions.

Defining digital for cultural organisations 10 Oct 2018 2:50 PM (6 years ago)

In the past couple of weeks I’ve had a few conversations about ‘digital’ in the cultural sector – the challenges, opportunities, and what to do about it all.

The thing is, a term as broad as ‘digital’ is only a useful shorthand up to a certain point. You can only get so far before you have to put the brakes on and say ‘wait, what do you mean by that?’

That’s because we use it to cover a huge list of activities, technologies, and processes that each have their own, very different considerations.

To make things easier, I’ve started trying to draw a line between the ‘administrative’ and the ‘artistic/mission-driven’ side of things. It’s not a perfect divide (and maybe those aren’t great names) but so far I think it makes more sense to generalise at that level.

Administrative digital

This covers any back-office functions that make use of digital media and technology (which is most of them). So that includes marketing, comms (although there’s an argument for this sometimes being in the other category), fundraising, ticketing, ecommerce, finance, venue management, volunteer management, HR… all that sort of thing.

If we’re talking about helping cultural orgs to make use of digital technology then, as far as this stuff is concerned:

- The cultural sector isn’t alone – the rest of the world is trying to figure out most of this stuff too, so solutions can come from anywhere. In fact, I usually recommend people start by looking outside the cultural sector.

- The benefits for going digital in these areas are mostly pretty evident. People don’t tend to need convincing, as much as they need help choosing, adopting, and making the most of what’s available.

- There are plenty of external people that can help – software providers, agencies, consultants, etc.

I think the key thing is that senior buy-in isn’t really all that critical. An Artistic Director, Chief Exec, or board member only really needs a passing understanding of the details so they can support and resource those areas sensibly.

Beyond that, it’s mostly about cultural orgs having sufficiently skilled employees and giving them the resources to do their jobs. Done right, digital media and technology should be able to make the back-office stuff run more quickly, effectively, cheaply, and/or profitably.

That’s not to say that ‘doing it right’ is always easy, or that hiring sufficiently skilled employees is always possible on the salaries available, but guidance is usually available for those who seek it out.

Sidenote: there are loads of agencies and software providers that specialise in working in the cultural sector. They solve problems across multiple organisations, giving them a really interesting viewpoint and making them amazing repositories of domain knowledge. In some cases they go to lengths to educate their clients. It often strikes me as odd that these people aren’t seen as more of a resource. Maybe it’s tricky to engage with the more commercial players and easier to turn to the publicly funded support agencies.

Artistic/mission-driven digital

This is much more specific to the cultural sector and there aren’t going to be many templates for success that can be imported from elsewhere (no matter how many digital transformation case studies you Google).

Here I’m talking about the work of directors, composers, curators, artists, musicians, educators, workshop leaders, etc (you get the idea). The thing that the audiences, visitors, and participants come to experience.

Senior buy-in is also going to be much more crucial here than it is with the administrative stuff. For two reasons.

Firstly, this activity is going to be much closer to the core of what the organisation is and does. It might even require them to make room in their programming – maybe doing less of what they’ve been doing up to this point. Unless they’ve been ‘doing digital’ as a box-ticking, inconsequential bolt-on to the real programme of activity, but what’d be the point of that?

Secondly, the case for digital activity in this area may not be as clear cut as it is on the administrative side of things. If it’s difficult to show a clear return on investment then you need a strong, senior advocate.

But here’s the tricky thing. I expect there’s a sizeable cohort of senior people for whom this kind of work is outside their comfort zone. They maybe don’t yet have the necessary frames of reference for what’s possible, or the common ground to have useful conversations with people who work in tech and the artists and others who are already active in this area.

Bridging that knowledge/comfort gap is a challenge, but it could be an important and interesting one.

That’s because the artistic/mission-driven digital activity has far greater potential for being transformative for an org than the administrative digital stuff.

A new CRM, or ticketing system, or website might be nice – even necessary – but they’re not going to be revolutionary. They’re not the point of the organisation. Whereas creating and presenting new types of work with new partners (artists and funders), reaching audiences in new ways could well be.

Everything is about people 23 Jul 2018 12:40 AM (6 years ago)

If you’re ever doing a talk about the state of the sector you work in and are struggling to think of something profound, try this simple formula:

“[subject matter] isn’t about [actually pretty crucial thing]. It’s about people.”

Then soak up the applause, give people a chance to tweet pictures of your incredibly insightful slide, and revel in your newfound role as a fearless iconoclast.

The great thing is, this works for just about anything. Here are some examples I’ve come across lately :

- Digital engagement isn’t about technology. It’s about people.

- Business isn’t about generating profits. It’s about people.

- Photography isn’t about cameras. It’s about people.

- Property isn’t about bricks and mortar. It’s about people.

Have a quick look on Twitter. I bet you find a few more.

I mean, I get what people are trying to say, but there must be a better way.

A website critique 7 Jun 2018 4:51 PM (6 years ago)

In a recent Cultural Digital email I said that a newly-launched website for a visual arts venue (I’m not naming them here) fell short in terms of “accessibility, performance, search engine optimisation, and other modern website standards/basic common sense”.

I wanted to write something a bit more constructive about the kinds of mistakes and omissions I spotted, so here goes.

Taking the four areas I mentioned in order…

1. Accessibility

You shouldn’t need perfect use of your body and senses to use a website. Just like you shouldn’t in order to enter the venue itself. As well as the obvious ethical reasons for making your website accessible, there are commercial and, possibly, legal ones too.

There are some standards for this. W3C’s Web Content Accessibility Guidelines are widely used. Let’s run the website in question past their most basic accessibility issues and see how it does:

- Page title: This should be an easy one. Each page should have a distinct title to tell people what page they’re on. However, on this site they’ve just got the website’s domain name as the title for every page.

- Image text alternatives (“alt text”): There’s no alt text for any of the images that I looked at.

- Text:

- Headings: There are no H1, H2, etc tags to give structure to the page and help people (or screen readers, or search engines) understand the structure of the page.

- Contrast ratio: In several places there’s not enough colour contrast between the text and the background. The WebAIM colour contrast checker can help with this.

- Resize Text: Finally, something that’s ok! You can resize the text in your browser and it doesn’t cause terrible layout issues.

- Interaction:

- Keyboard access and visual focus: Some of the most important elements aren’t accessible via keyboard shortcuts – specifically the menu and any of the buttons to buy tickets or memberships.

- Forms, labels, and errors (including Search fields): This is fine.

- General:

- Moving, Flashing, or Blinking Content: This is generally fine, although there is some overlapping text in some places.

- Multimedia (video, audio) alternatives: I didn’t spend much time looking for multimedia content. I did find a YouTube trailer and it was possible to select and control that via keyboard shortcuts, at least. There was no transcript though.

- Basic Structure Check: Everything’s laid out in the right order, but it’s as if structural, semantic HTML doesn’t exist – it’s just div after div. Designing With Web Standards came out fifteen years ago but the lessons still apply.

All in all, that makes for gruesome reading, and I’ve only just scraped the surface.

A proper accessibility audit needs to be done manually but, if you’re interested in getting a headstart, you can get some of the way there with a few tools. Google’s Lighthouse is one.

Lighthouse scored the site 10 out of 100 for accessibility.

2. Performance

This is all about how quickly the site loads for the user. Site speed is important for all sorts of things, not least a decent user experience.

Site speed tests don’t tend to tell you how fast the site loads as such, because that depends on a person’s internet connection. Instead, they look at the size of the website you’re serving up, and then look to see how many techniques you’ve used to deliver the website as quickly as possible.

This site is pretty simple, but still manages to be a lot slower than it should be. The main problems are:

- The images. The sites asks you to download much larger ones than it needs, shrinking them down in your browser. They’re also not optimised.

- The site could also make use of caching.

- It could also handle the 12(!) CSS scripts better.

Of the tools for grading website performance:

- Lighthouse scores the site 8 out of 100.

- Google PageSpeed gives it an F.

- YSlow gives it a C.

3. Search engine optimisation

If you want to show up in search engines for relevant keywords then you need a website that features relevant content, that’s easily understandable by search engines, and that’s linked to by other relevant and reputable websites.

With cultural organisations there’s often minimal competition for the most relevant keywords and their sites usually attract good quality links without much effort. If you just care about being found by people who already know you exist, then that’ll usually be enough. You can even get by with a poorly optimised website.

That said, there are still plenty of reasons to get the basics right.

Many of the accessibility and performance issues above are also basic aspects of search engine optimisation. A quick glance shows that the site is also lacking:

- The name of the organisation on the homepage.

- A robots.txt file.

- Schema markup.

- Meta descriptions for each page.

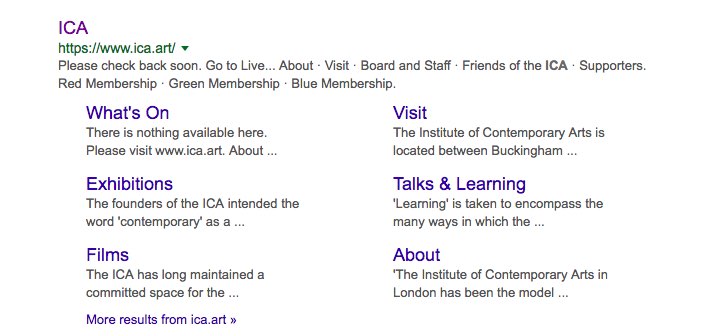

On that last one, Google displays the meta description on the search results page when your website shows up.

If you don’t set a meta description for each of your pages then you’re at the mercy of whatever Google happens to pull out. Here’s a random example of what can happen…

You don’t really want phrases like ‘Please check back soon’ and ‘There is nothing available here’ showing up.

4. Other modern website standards/basic common sense

There are some other technical issues, and some others that I’d flag as potential usability banana skins. For instance…

- I’m willing to bet that a quick test (on something like UsabilityHub) would show that nobody can guess where the menu is.

- The homepage defaults to showing what’s on, but shows today’s date at the top. That confused me, because I was looking on a Monday and they’re closed that day.

- The date picker feature is just a pain all round.

- Can you guess the difference between Red Membership, Green Membership, or Blue Membership? Those are the titles shown in the menu.

- There’s no Open Graph markup.

I bet there’s more. I’ve only looked at a few pages.

UPDATE: I ran a very quick test and yeah, 84% of people failed to guess where the menu was. That’s crazy. They also took on average of 30 seconds to complete the test – that’s a lot of time to do such a simple task.

It’s common enough to use a logo as a link to the homepage (and from the user testing I’ve done before, even that’s not universally understood), but I’ve never come across it being used to open the menu before. Apparently I’m not alone.

To sum up

There’s nothing here that can’t be fixed, and presumably the website is a work in progress. But…

It’s not as if the things I’ve pointed out here are fancy ‘nice to haves’. They’re the basic building blocks of a competently built website. This stuff isn’t hard, and I really can’t see why a progressive, forward-looking organisation can’t reach that minimum level.

Finally, I just want to make clear that I’m not talking about the general look and feel of the site here. That’s much more of a subjective thing. It’s not my cup of tea, but then I don’t think I’m their target audience.

Lessons from The Library #1: Cultural organisations and ecommerce 1 Feb 2018 7:45 AM (7 years ago)

The Library contains a spreadsheet with the CMS, ticketing platform, donations platform, and website designers/builders of 350+ of the largest UK cultural organisations.

I’ve just added a column to that spreadsheet showing which ecommerce platforms those cultural organisations are using for their online stores.

Of the organisations in my sample, 22% have an online shop. The others may well have some sort of ecommerce functionality but, rather than selling merchandise, they’ll be focused on some combination of tickets, memberships, and donations.

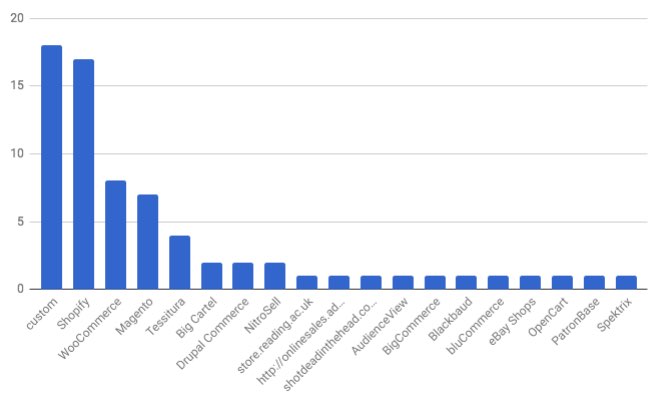

The chart below shows which ecommerce platforms these cultural organisations are using.

In case the chart is too small for you, or you’re using a screen reader, those are:

- A custom solution

- Shopify

- WooCommerce

- Magento

- Tessitura

- Big Cartel

- Drupal Commerce

- NitroSell

- … and various others.

A few observations

I’m not surprised to see Shopify up there. Most of the online shop launches I’ve seen over the past year or so have been on Shopify. I also wouldn’t be surprised if some of those custom solutions were replatformed onto Shopify over the next year or so.

Not that it’s always necessarily the right choice – copying everyone else is rarely a good guide. There are lots of considerations that might affect your choice of ecommerce platform.

However, from looking at who’s using what, a few trends seem to emerge:

- For a small to medium-sized, standalone offering, Shopify is a popular choice.

- If you’d like to integrate products into a WordPress website then WooCommerce might well make sense. The same goes for Drupal and Drupal Commerce.

- If you have a large shop with some complicated requirements then there may be a case for Magento.

- If you’ve got a very limited offering that’s closely tied to your ticketing offer (ie programmes and vouchers for ice-creams) then you might be able to get away with using your ticketing system.

About The Library

The Library is a constantly growing collection of information and resources related to the digital aspects of cultural organisations.

If you want to know which organisations are using the various ecommerce platforms (and much more besides) then join up and explore the data.

Launching the Library 22 Oct 2017 4:34 AM (7 years ago)

I’ve launched a thing called The Library. Here’s a bit of background for anyone interested in the what, why, and how.

First up, in case you’ve not already, then pop over to The Library and read the FAQ. That should cover the basics.

What

The Library sits under the Cultural Digital banner – that’s the name of the weekly email newsletter I send out – and it’s a subscription service. Sign up and you’ll get access to a Google Drive containing info and resources relevant to how cultural organisations are making use of digital tech and media.

I reckon it’s very useful and pretty cheap. £200/year compares really well to the sort of fees research firms charge for their subscriptions, and I know I pay more than that for memberships and SaaS subscriptions that deliver much less value.

The Library is in very soft launch mode at the moment and will open properly in very early November. If you sign up now then you can save a whopping 50% off your first year.

Why

There are quite a few reasons for this.

Perceived need. A couple of years ago I put together a Google Sheet with lists of digital agencies (and others) that had experience of working with arts organisations. People seemed to find that really useful but I could only find the time to update it very occasionally. Although it wasn’t the intention, that has served as a kind of MVP for the Library.

Another thing is that in my consultancy work I get asked a lot of questions about what systems people are using, which agencies everyone’s working with, whether there’s a certain type of job description out there they can take inspiration from… that sort of thing. Previously, there was no quick and simple way of getting hold of that information. The Library fills that gap.

The number of early sign-ups so far has reassured me that the perceived need is an actual one so, fingers crossed, that’s the idea successfully validated.

Spreading the cost. I have to stay on top of this information in order to do my work, but it’s not the work itself. Collating it all takes a considerable amount of time and expertise and I can’t see any one client paying for it. Spreading the cost among lots of people would make it sustainable, allowing me to justify dedicating time to making it more comprehensive and keeping it all up to date.

A more informed sector. I can only work with so many people one-on-one. If there’s a way for the sector’s organisations, consultants, funders, and suppliers to all be that bit better informed then that’s a good thing, right?

An experiment in selling an info product. I like to learn by doing things. I’ve never run a subscription-based service before so this is a chance to do that. I fully expect the lessons I learn here to carry over to other things I do.

Selling my by-products. Years ago I read a Signal v Noise blog post about selling your by-products and it’s an idea that’s stuck with me since. In a sense, that’s what I’m doing here.

How

Here’s what I’m using to put this together.

The website was built very quickly with Strikingly. However, the subscription payment platforms you can integrate with are a bit ropey, so for the time being I’m taking one-off payments using Typeform, which integrates with Stripe. In turn, Stripe sends money through to my bank account and connects to Xero, my accounting software.

The payment bit will need to be revisited soon because it’s a long way short of adequate. However, it’s enough for me to launch with. Perfect can wait a little while (yay agile!).

A few simple automations kick in when someone signs up:

- An excited message turns up in a Slack channel.

- Their details are added to a Google Sheet so I can keep track of when they’re up for renewal.

- Their email address is added to a list in Mailchimp

- Mailchimp sends a welcome email apologising for the lack of automatic receipt and linking to a Typeform survey so I can find out more about their expectations

I’m mostly using Zapier for those automations.

Google Drive is the hub for all the resources. Library members will be given a login to a top-level folder with lots of very nicely ordered folders, spreadsheets, and documents.

Interested?

Sign up before it launches to get the first year for £100.

What Tristram Hunt actually said about digitising collections 2 Jun 2017 6:38 AM (7 years ago)

“we’re very passionate about it, we’re strong on it”

If you worked on the digital side of the museum world I imagine you’d be pretty chuffed to hear a high-profile museum director publicly supporting this kind of work. Right?

But if you were following the reaction online over the past couple of days you’d have thought he’d suggested sacking the V&A’s (consistently award-winning) digital team, ripping out the building’s wifi, and deleting their entire online collection.

So what happened?

In case you’re not up to date on this one, Tristram Hunt is the recently-appointed director of the V&A (or a “novice museum worker” if you want to get all ‘not one of us’ about it, as several did). He recently gave an entertaining talk at the Hay Festival about the V&A’s history, then answered questions from the audience about acquisition policy, plywood, and using technology to make their collection more accessible.

His answer on the last topic was reported in The Times (Museum visitors seek refuge from digital world) before being increasingly misinterpreted:

- The Memo: V&A Director: We’ve been doing digital art all wrong

- Gizmodo: Digitising Museums is a Waste of Money, Says V&A Boss

- Confusing digitisation of collections with digital art

I wouldn’t bother clicking any of those if you’ve not already read them, but keep the headlines in mind for later on.

Now, I got a C in GCSE History a couple of decades ago, so I’m fully aware of the benefits of going back to primary sources.

The Hay Festival website has a rather wonderful thing called Hay Player. Audio recordings of talks going back several years can be found there, and you can pay £1 to download one. A small price to pay.

Here’s where you can get a recording of Tristram Hunt’s speech and the Q&A that followed it. I highly recommend giving it a listen. The bit we’re interested in starts around the 54 minute mark.

I hope the good people at Hay don’t mind me reproducing the question and answer.

[Question from the audience] “You’ve talked about making the art more accessible for people in regional locations but you didn’t talk much about how technology can help you to do that. So I’m wondering if you have strategies around using the internet, social media, apps, etc to make things accessible.”

[Tristram Hunt] “Yes, this is a really strong and active area of debate. In one of our new galleries you can, on your iPhone, download your own personal guide to the contents of the galleries. And it’s done beautifully – there’s music, the curators talking… but you’re wandering around listening, either with your headphones or listening to your iPhone, whilst looking at the artefacts.

And actually it hasn’t proved that popular. There’s a sense of people often coming into the museum as a way to get away from digital activities. And what we’ll find is that they’ll then go home often and want to look at what they saw today, or they’ll be in the cafe looking at it, so they’ll reflect afterwards through digital media and digital access on what they saw, but in terms of their own personal interaction with the object, often they want to step back from that.

At the same time, what we’re involved in is a massive programme of digitising our collections. But again, it’s a debate. There’s a very big debate in the museum world about the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the amount of investment they put in to digitising their collection, which means that you’re taking it away from other areas.

And so we’re very passionate about it, we’re strong on it, but it’s rather like the newspapers – no-one’s got the answer yet about what you should do.

What I’m very passionate about is ensuring that we’re giving teachers the professional development and advice they need to be able to access our collections online to inform their teaching.

So if we pursue it though a more education-focused lens, that would be my ambition”.

[end]

That doesn’t sound so ridiculous, right?

To recap:

- He didn’t say he was about to “bin spending on digitising collections and creating apps, audio tours and other digital content, as he thinks the average museum punter isn’t interested in any of it”.

- He didn’t confuse digital collections with digital art. He didn’t even use the phrase ‘digital art’, and certainly didn’t say that anyone had been doing it all wrong.

- He didn’t say that “digitising museums is a waste of money”.

What he did say is that there’s a debate about how in-gallery technology might best be provided. I think that’s fair, and there are plenty of very interesting projects and experiments we could all point to that are exploring this area.

We might disagree with the assertion/assumption that people want to get away from interacting with digital technology in galleries, but there’s grounds for a debate (see the comments on the Times article). A more nuanced position is likely to be summed up by any or all of these:

- museums can be improved by in-gallery tech done well

- museums can be worsened by in-gallery tech done badly

- museums can work well without in-gallery tech

With a big fat ‘it depends on the circumstances’ bolted on.

Tristram uses the example of an audioguide in one of their galleries not being massively popular, and of course, we all know there are plenty of reasons why uptake of a particular thing might not be great. But you don’t even have to leave the building for an example of in-gallery audio technology being integral to the experience – see the current Pink Floyd exhibition that’s had rave reviews.

It’s also true that there’s a debate about the amount of museum resource that should be allocated to digitising collections. The particular merits of the Met Museum case can (and have been) debated too, but his key point seems fair enough to me. Museums don’t have bottomless reserves of cash and there’s a perfectly valid discussion to be had about how activity within a museum is prioritised.

So go back to those headlines again. How well do they line up with what was actually said? And where did some of those quotes comes from?

In the interests of transparency, I should mention that the V&A are one of my clients. I’ve never met Tristram Hunt though, and I didn’t speak to anyone there about this post before hitting ‘publish’.

A post about a comment 31 May 2017 11:05 AM (7 years ago)

Lots of blogs still have sad, neglected little sections exhorting people to “Leave a Reply. Want to join the discussion? Feel free to contribute!” at the end of each post, even thought all the conversation’s (mostly) long since moved on to other places.

So if you do go to the bother of paying attention to what someone’s written, and then take the time to leave a considered comment, only for it to be deleted… well, that’s annoying.

Which is what happened to me a couple of months ago. The good news is I have my own blog as an outlet for this sort of thing, and I’m screenshot-happy, so my comment wasn’t lost forever.

So anyway. A ticketing supplier put out a post titled “Google Analytics Dashboards – What’s On Yours?” (the lack of link is deliberate). I do a lot of work with ticketed venues (theatres, arts centres, museums, etc) and Google Analytics is very much my bag, so this was right up my street.

It wasn’t a bad post, but a couple of things caught my eye. The main thing was this table…

Being the eagle-eyed type, I noticed a few issues with the data in that table, so I left the following helpful (I thought) comment…

The traffic sources screenshot is interesting. At a guess, I’d say there’s an issue with cross-domain tracking that’s not been solved properly. Revenue from direct traffic is unusually high, which would be fine on it’s own, but revenue from organic is weirdly low. The two together point to a problem. Usually you see this when the website’s domain has been added to the referral exclusion list in GA, but the tags on the pages aren’t behaving like they should.

Also, the 4th line of that table – it’s been redacted, but I’d guess that’s a self-referral. It’d explain why, of 6,000 sessions, none are from new users.

So my guess is that a lot of revenue is being incorrectly attributed to ‘direct’, making a mess of any ROI calculations and meaning that other marketing channels aren’t getting the recognition they deserve.

I tried to phrase it gently, or at least in a ‘huh, isn’t that interesting’ way. Thing is, this is one of the most fundamental, but also very common, errors that I come across when auditing Google Analytics accounts. I won’t go into it here but it’s not good, causing double-counting of sessions and ruining marketing attribution.

It’s really not the kind of thing you want to be showing off in a blog post where you’re trying to claim how great you are with analytics.

There were two more issues with the post.

One was very minor. The Google Analytics Shopping Report (an enhanced ecommerce feature) was referred to as the Checkout Funnel, which is a different report. Like I say, no biggie

The other was more major. The post ends with “if you would like some help getting these up and running, please don’t hesitate to get in touch.”

As you’ve probably gathered, doing that would be a mistake. If you want a hand with your analytics then you’d be much better off getting in touch with someone who knows what they’re doing.

To be honest, I didn’t expect my comment to be published. I thought maybe they’d correct the errors I pointed out and drop me a line to say thanks for helping them to avoid looking like idiots. You’d have thought that would have been easier. Ah well.

Online fundraising: donate buttons and the need for context 16 Oct 2016 11:40 AM (8 years ago)

I was flicking through a copy of Now, New and Next, which is a magazine from the Arts Fundraising and Philanthropy programme.

There’s a good article about how smaller organisations are diversifying their fundraising efforts and it calls out a few small changes that are making a difference…

Putting in place simple response mechanisms such as donation buttons positioned prominently on websites, collection boxes, and offering the opportunity to top-up the ticket price.

I want to pick up on the ‘donation buttons positioned prominently on websites‘ bit and add something so that people don’t get the wrong idea.

It’s this. I’ve seen websites with donation buttons sprinkled all over the place, I’ve fielded requests to add them (back in my web design agency days), and I’ve seen the stats showing hundreds of thousands of people across multiple websites all ignoring them.

You know that awkward thing where someone goes in for a kiss and the other person dodges?

That’s what it’s like seeing those buttons littered around the place.

That’s not to say you can’t ask for a donation online. Of course you can. But context is key.

A donation button should be there, ready and waiting, when:

- You’ve provided some sort of value to someone. For instance, if someone has been allowed to download all your podcasts or learning resources then absolutely ask for a donation towards the cost of producing and maintaining those things.

- The person already has their credit card out. A simple message at the point of making a transaction can work very well.

- On a landing page for an email/social campaign. You’ve warmed the recipient up to the idea of a fundraising campaign in their inbox or news feed, they’ve clicked through and the call to action on your landing page is there to seal the deal.

You may have your own things to add to that list, and I bet the context is stronger than ‘the person just happens to be on the website’.

It’s why these days the smarter sites are falling over themselves to offer you an ebook, a chance to win stuff, access to a back catalogue… something in order to pull you in. That offer is their most prominent call to action. The idea is that once the person is (contentedly) hooked they can then start building a (more lucrative/engaged) relationship with them. There are even whole products built around this premise.

So to sum up, from what I’ve seen, ‘donate’ buttons on every page on your website are likely to be ignored. If that’s the best you can do for now (and the article was aimed at smaller orgs) then fine, I get it. But I’d highly recommend doing something that brings the person into a context where they’re more likely to want to donate to you. Then you should make the ask.