What's the Worst that Could Happen? 19 Jun 2022 4:26 PM (2 years ago)

We’d invited Mom and Dad to come to Egypt with us, thinking that it was time they traveled again. They’d been all over the world but the difficulties of caring for aging parents and then COVID had brought their thrill seeking to a halt.

“What’s the worst that can happen Dad?” I said, coming over to the house to make my case in person. “We’ve all been vaccinated–the biggest worry is that you’d get COVID and have to deal with an Egyptian hospital, but you’ve got the shot. That’s off the table. You haven’t got any more risk now than you would in a normal year.”

“But there are so many travel restrictions. We’ve got to get tested to get back home. I don’t think it’s a good idea.”

I puzzled at the strangeness of this. Dad had raised six kids and been a leading businessman in the community since the 1970s. He’d always understood calculated risks and was an imposing figure to most people. In any room he was the dominant persona and I’ve often joked that he’d preside at his own funeral. Something about COVID had made a dent in that armor. He needed this trip.

“There are places all over Cairo for speed testing, tailored for travel. You can get your test and be ready to go. And let’s just say, for the sake of argument, that you can’t get your test results in time–it would be no different than if you missed a flight. People miss flights all the time and seem to survive. What’s the worst that could happen? You have to push your flight back a day and end up spending another night on the Nile at a 5-star hotel? I can think of worse fates.”

There was a pause as he pondered this. “I’ll think about it tonight and get back to you.”

The next day he called back and with the same tone as if he’d been holding a press conference to announce a new trade policy or a presidential pardon he said, “Your mother and I have decided to join you in Egypt.”

My elation lasted until it was time to leave. With all my cockiness about how easy it would be, I was now all nerves as Andrew and I boarded the plane for Seattle. Eating had been a little iffy that morning and I tried to convince myself that international travel always has its unknowns, and Egypt would just be another unknown until we knew it. Take a deep breath, when you’re back home again after a great trip you’ll be living on these memories. It’ll all be fine.

It was 5:15pm when Andrew and I landed in Chicago to connect to Frankfurt, while Mom and Dad would be coming from Virginia and going through Paris. We took our time during our layover, working out a few issues with our bags being checked through and making sure we had all our boarding passes before heading toward the Lufthansa gate. Andrew ran to the nearby bathroom, taking his time to freshen up in between legs and I stopped to grab some hamburgers. With about 45 minutes to departure and knowing that they’d soon be boarding, I decided to wait for Andrew in the boarding area and handed the gate attendant my papers. She took one look at my negative COVID test printout and said, “I’m sorry, you cannot board with this test. It’s too old” and handed the paper back.

She was so calm about it, as if that was all there was to be said. I wasn’t sure I’d actually heard her right. What? I’d been meticulous in every detail, had checked everything.

“But no!” I protested, thinking she couldn’t read, “Look, it’s negative. Egypt requires a negative test within 96 hours of entry–this works!”

“I’m sorry, but Germany requires a test within 48 hours.”

“But we’re not going to Germany, we’re going to Egypt! Germany is just a layover!”

“It doesn’t matter, even if you’re only in the airport a test is required.”

The horror sank throughout my body. I’d researched everything, looked at every website, every embassy, checked up and down, had jumped through every hoop, and no one told me this!

“Well,” she said nonchalantly, looking at her watch, “If you hurry, you can leave the airport, go across the street, go to the rapid test station there and then come back. You can still make the flight.”

I looked at my own watch and I did not believe her for a second. It was my first time at O’Hare and I had no idea where “just across the street” was and if it’s like any other airport there was absolutely no hope. No hope. Lost. Gone. Dead.

She handed me a sheet of paper with a huge QRC code on it and some vague writing about a testing center “just across the street” from the terminal near the bus station. Andrew returned from the restrooms in time to see me snatch the paper and turn, launching into a sprint down the terminal.

“Where are you going??” he yelled, running after me.

“Come on!” I shouted over my shoulder, “Follow me! We’ve got to get a COVID test!”

It’s to his credit that he followed–what faith to run after an obviously insane person–and soon we were both sweating in streams as our bags jostled up and down against our backs. We wove between people with an “I’m sorry!” or “Excuse me!” worthy of an episode of The Amazing Race and it was lucky in a way that we had a long run ahead of us because it gave me time to collect my thoughts.

There was no way we were going to get the test and make the flight. No way. But we were going to have to get a test if we wanted to make any kind of a flight later on. If they were able to rebook us we’d still need that test so we might as well give it everything we could.

Every once in a while I’d hear Andrew protest with “We’re never going to make it!” though said more to himself than to me. It was obvious that I wasn’t stopping to reason things out, he was carried along by the momentum of my panic. I was angry, I was shocked, and I was terrified, but I was also praying hard something like, “I know I’ve done a lot of dumb things, and I know this is somehow my fault. You’ve helped me out of scrapes before when I didn’t deserve it, if you can find it in your heart to reach down one more time . . . .”

When we stepped onto the pavement outside the airport there were three lanes of traffic directed by an airport worker. We stood, waiting with all the other pedestrians, impatient for the uppity pseudo-cop to notice us and stop the flow for us to pass, but he didn’t even glance at us as he slouched, hands in pockets. A minute went by and then I’d waited long enough. I stepped out into the slow-moving cars with my hand up as if I were one of the Avengers and could control objects with my mind. I worked my way through the three lanes before he really noticed me and then I was off, sprinting once again to my unknown destination with him shouting after me, “I’m gonna have to report you!”

“You’ll have to catch me first,” I thought, betting that he’d rather not have to move, as I rounded the corner of the parking garage and headed for what I hoped was the mysterious bus terminal referenced on the paper I still clutched. Andrew had watched this all go down, certain that I was going to die or be arrested or shot, and had worked his way along the curb until he’d found the crosswalk and made it through the break in traffic that my jaywalking had created to join me. The paper said something about a Hilton and I could see a hotel sticking up 100 yards further down.

I saw a folding standup sign advertising a walk-in COVID test center and I jerked open the doors in relief. Far down the terminal was a small group of people and I made for them.

“We need to get our COVID test right away!” I panted, “Is there any chance we could cut in line and do it now? Our flight leaves in . . .” I glanced at my watch, “Twenty minutes!”

They were remarkably nice about it; in hindsight I’m impressed at their willingness to move aside and let two very sweaty people jump in line.

“You’ll need to scan this QRC,” the man in charge drawled, “Then fill out the forms.” Why was he talking so slowly? It was nightmarish how slow he seemed to be moving.

I fumbled with my phone, trying to scan a huge wall poster that refused to be scanned, before giving up and heading straight to the url.

“My phone battery died!” Andrew moaned, remembering that his phone had gone dead just as we’d landed.

As I worked my way through the awkward six signature pages, filling out fields, then going back to fill out more fields that I’d accidentally skipped or filled out incorrectly, then having to redo it all when the page refused to load, I was sure that I was going to have an aneurysm. No one could live through pressure like that and live. But I finally got my application submitted and then went back to work on Andrew’s.

Five minutes later they were calling us up and swabbing our brains with a lot less compassion than they might have had, and with a nod and a thanks we grabbed our bags and dashed to the doors.

Once outside it was even more confusion as I faced what I’d known was going to happen: how do you get back into an airport quickly, let alone through security and to the gate? We weren’t at the main entrance, there were no signs, and you know how security is. If we didn’t choose the right way in, we’d get dead-ended and have to return outside.

We started running toward the terminal, retracing our steps but avoiding the angry fake traffic cop, and stopping every so often to grab a stranger and scream, “Which way to the terminal??”

We made our way up escalators, down corridors, past the checkpoints and down to security where I knew we were going to lose the whole game. No way could we get through O’Hare’s security, even with our PRE passes, in time. But remarkably there were few people going through and the ones who were there let us blaze ahead and we got through–luckily without TSA thinking that we had to be dangerous with the crazed look and freak-out panic we were displaying.

I kept checking the countdown on my watch. Twenty minutes, fifteen, ten–everyone knows they close the gate on international flights well before a departure–how soon would it be closed? Would they hold it for us? There was no hope. But there we were, back at the Lufthansa gate with the same German woman who looked up and smiled at us as we streaked in, reentering the atmosphere in flames.

“You made it,” she said calmly, smiling. “I told you you could.”

Though I did detect a note of surprise in the subtext.

I wanted to point out that she’d said we might make it, but I didn’t care.

“Have you got your test results?”

“They haven’t come through the email yet.”

“They will. Just wait over here please,” and she directed us to stand to the side. Not that anyone else was coming, the flight was scheduled to leave in five minutes.

Refresh. Refresh. Refresh. Why wouldn’t it come through? Then it was there, bold and beautiful in my inbox. I jumped up to show her.

“Did you get them?”

“Right here,” I said, extending the phone toward her.

She didn’t even look at it but took our passports and put a light blue dot sticker on the back. “You’re fine to board. And that was it. I still had the bag of hamburgers, clutched in my hand without realizing it and soaked through with grease on the bottom.

When we dropped into our seats I thought about Mom and Dad. They were connecting through Paris–did France have the same rules? I’d guided Mom and Dad through the bureaucratic process of getting their papers and tests but had obviously overlooked some important things. Would they get stuck too? They were coming from the east coast, maybe their tests were within that window.

I couldn’t worry about it.

When we met up the next morning in Cairo, the four of us sat together for breakfast on the terrace of the Sofitel Cairo el Gezirah with fresh squeezed orange juice and pastries.

“How did your flight go?” I asked them, taking it as a good sign that they were actually there with us.

“Oh it was wonderful! It all went so well, just like a charm,” Dad said. “How was yours?”

66'33" 19 Jun 2022 4:24 PM (2 years ago)

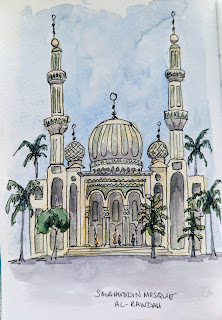

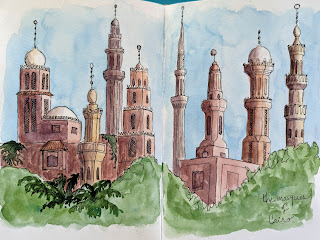

I've been gone so long I thought I'd never touch blogging again. So long that the kids are all grown and gone, some of them married, and Andrew and I spend our time traveling and enjoying life just the two of us. We live in the same house in Anchorage and he's built up his business in the decade since I've last written. I've taken up watercolor, oil painting, and urban sketching and play the harp while planning our next travel adventure.

In January my brother Luke took me camping above the Arctic Circle. We left Anchorage early Monday morning and drove north, passing Denali and following the pipeline to Nenana and then the Yukon River.

Baksheesh 19 Jun 2022 4:20 PM (2 years ago)

You can’t get Egyptian money in the United States. What I mean is, you can’t order any bills through the bank or a currency service, you have to wait until you get there to exchange currency. This causes a little bit of a problem because you need cash in Egypt–lots of it, in small 10 or 20 Egyptian pound notes–otherwise you can’t get much done in a place run by baksheesh.

Tipping arouses strong feelings in America. We are a freedom-loving people, resentful of authority and happily married to capitalism so just tell us what it costs and we’ll either buy it or we won’t. Don’t try to extort more from us. A purchase isn’t a nuanced dance of negotiation, it’s a black-and-white contract where you have what I want and if I want it bad enough I’ll pay you the agreed upon purchase price. Don’t come back with your hand out, telling me the deal wasn’t enough.

Regardless of whether you call it a well-deserved bonus for a job well done or panhandling, tipping is everywhere in the States so that when I travel to other places and find that they generally don’t have the same tipping customs I do a dance of joy because the vacation just got that much easier. To know there’s no expectation of more once you’ve paid the tab or got out of the taxi is a relief . . . but not in Egypt.

Tips are expected for everything. Cabbies, waiters, doormen, concierge, airport personnel, bathroom cleaners, docents, that guy on the street who gives you directions . . . it does not end.

We were in Edfu, forced to take a carriage from the pier to the temple of Horemheb, as provided and previously agreed upon by the cruise director. As we left our boat we were told that it was customary to tip the carriage driver with about 10 pounds. Putting aside the experience of careening through the streets of Edfu behind a slathering, cantering horse with a driver who would twist in his seat to smile sycophantically and repeat “America number one!” Putting that aside, when we were done we did as had been suggested and handed the driver a bill. By this time Andrew had learned the art of folding money into a tight package in the palm of his right hand so that he could shake hands and say, “Thank you very much” then stealthily discharge the money like a spy making a hand off of nuclear secrets on microfilm.

Bad news though, this apparently wasn’t enough and the driver got angry, discharging his own stream of abuse at us as we fled for the pier. He felt cheated, we felt cheated, it was an exchange that left everyone unhappy.

We were in the Cairo airport waiting for our flight to Frankfurt and completely out of Egyptian cash–and we’d timed it that way since you can’t exchange it once you leave, if you recall.

Sitting in the waiting area at the gate Andrew needed to use the restroom. An airport worker with a large cleaning cart was hanging around listlessly and, when Andrew emerged from the bathroom, angrily demanded a tip. I watched it go down and as Andrew returned to his seat I braced myself for more confrontation. The only thing we had going for us was that the worker was in a predicament: if he left his post to chase Andrew down he’d miss the others coming out. How much was it worth to run down the American?

Egypt takes its tipping so seriously it’s developed a whole new system around it: baksheesh, which is really just tipping on steroids and it doesn’t help that to Egyptians, we Americans look like a pile of money on two legs. The United States is some vague thing that represents money and privilege and we Americans are easy to spot (or hear). But then, Egypt has been hit hard in recent years and tourists have been a trickle of what they once were before the Arab Spring and Mosi arrived on the scene. Add to that COVID and the country is desperate for tourists and will do everything they can to present a pleasant and safety-conscious face to the world, begging the West to return and bring money with them.

So besides wanting to keep Americans extra protected, able to tell stories back home about how wonderfully safe and accommodating Egypt is, the police generally don’t want us to go home complaining about being hassled for bribes. And then it also helps to feign ignorance with an appropriate, “No habla Anglais” shrug when someone approaches you with his hand out because for all their audacity, the transaction has to be done on the sly or it looks bad.

We had hired a cab to take us from our hotel in Cairo to a building in Maadi where we’d attend church. We scheduled the pickup with plenty of time and because of the traffic around the hotel lobby we decided to walk out 100 yards to meet our driver at the entrance. We loaded into the van and settled ourselves and were approached by a white-uniformed police officer who gestured to Hassan to roll down his window. Serious discussion ensued though I didn’t pay that much attention–I’ve learned that I’m terrible at properly interpreting emotions through the intonations of language so I tuned most of it out until it ran on longer than was normal. Soon papers were being passed through the open window and more discussion followed and Hassan seemed rather sheepish and submissive.

What was going on? The officer walked away to his booth to examine the papers and Hassan turned around in his seat.

“If they ask you, you are Australians.”

Huh?

That didn’t sit well with my father, who quickly pointed out that he’d made it a habit never to lie to the police and my attorney husband instantly agreed. Me? I was ready to throw a shrimp on the barby with a hardy “G’day!”

In the end it took us ten or so minutes to get them to let us go, by which time Dad was convinced they had it in for Americans and that we should stick to the story of being “from Alaska” because even most Americans couldn’t locate that on a map and it would preserve our integrity, but it turns out that it was actually the opposite.

Hassan—or rather our friend Aton who owned the van—hadn’t filed his paperwork properly. The government likes to know exactly where Americans are being shuttled, not for sinister reasons but out of an abundance of caution. Who wants to tangle with the Americans if some of their kind should happen to get themselves into trouble somewhere? Keep track of them and keep them safe. Aton had been lazy and didn’t want to file and the police were ticked that he’d cut corners. I imagine some baksheesh solved the problem because we were soon on our way.

We were in the Cairo airport halfway through the trip, traveling to Luxor, when we had to go through the security metal detectors. We were behind what appeared to be a wealthy Egyptian man of about 65, wearing a djellaba and accompanied by his son who looked to be a young professional. We put our things on the conveyor belt and waited our turn, watching the bags closely in case someone should try something.

It only caught my attention after the third time that the old man couldn’t get through the detector. The security people kept sending him through and I wondered what was setting off the machine. Then, on the fourth try I saw the man reach into his pocket and pull out a wad of bills. He handed a few over to the security guards and walked through without a hitch.

“Did you see that?” I hissed at Andrew, “They just shook him down!”

Knowing it was our turn I wondered what we could expect. With the commotion the old guy had caused we took advantage of things and slipped through, reaching for our bags on the other side. A guard at my shoulder stopped me.

“Boarding pass!” he said firmly. A big red flag, because you can’t get your domestic boarding passes before you get to the airport, you have to get them once you’re inside and at the airline check-in desk. But I’m sure he knew that, we were only at the front entrance. I thought quickly.

“They’re in my bag,” I said, wanting to get to my bags as soon as I could and buying for time.

Stuff was still going on with the old man and his son and it was enough of a distraction that I made it to my bag and had it ready to wheel off a second later. Andrew was right behind me.

“Grab your stuff quick!” I whispered. “I think they’re going to want money.”

And quick enough, we got through and were off before they realized it. I figured if anyone questioned us I could play stupid as if I didn’t know what was going on, which is what Dad did when he and Mom came through right behind us. Security tried to hassle him a bit but he’s big and imposing and pretty much shrugged them off as if he didn’t understand. About that time a police officer wandered by and saw what was happening, dressing down airport security and letting us through without further incident.

But that’s business as usual in Egypt. The Egyptian gentleman didn’t seem particularly surprised or ruffled by the experience. Prepared, you might say. But then life there seems to nod to those things outside of one’s control, exemplified in the phrase inshallah--God willing. You hear it everywhere, sometimes simply as punctuation.

“What are you studying at university?”

“Mathematics, inshallah.”

“Is your daughter still seeing Abdul?”

“Yes, they’re to be married after Ramadan, inshallah.”

“I’ve got to get to the dry cleaners after work. Inshallah.”

To Americans baksheesh is a graft, a bribe, and we’re galled by the audacity and corruption but in Egypt it’s de rigueur–part of the economic structure–so why fight it?

“Did you enjoy your trip? How was Egypt?”

“We loved it! It’s a great place to visit. Inshallah.”

Dramatis Personae 19 Jun 2022 4:00 PM (2 years ago)

I stepped out of the cool, dimly lit mosque of Muhammed Ali into the heavy sun soaking the terrace above the dusty buildings of Cairo. Coated in a dull shade of ochre and dirt that had thickened through the rainless years, each structure blended into its neighbor in the layers of smog that obscured our view of Giza to the south. We were at the silver-domed Citadel, or Salah al-Din Al-AYoubi, where the medieval nemesis of Richard the Lionheart had built a fortress to protect Cairo from the crusaders.

We’d taken our shoes off to enter, passing trios of visitors sitting cross-legged on the red carpet and propped against the support columns as they listened to droning guides, and exited the other side onto the terrace where the light blinded me. At the stone railing, with the dusty mudbrick city as a muted backdrop, stood a full-bearded blond European in brilliant white linen--from skull cap to kaftan. This Viking stood with his arms stretched to the sky and his face tipped upward as he swayed in the breeze that fluttered his garment. A second man sat observing while a third, wearing a shoulder-mounted camera, filmed the scene.

He was a Belgian rapper making a music video and, in my opinion, doing a smashing job.

Andrew and I came to Egypt at the end of COVID, convincing Mom and Dad to join us, and while I snapped a lot of pictures of pyramids and obelisks, it was the people that I took home as my treasured souvenirs. There was Cathy Jones, the manic United Airlines ticket agent, with her gravely voice and thin, straight hair that blocked her face so that she peaked out at the world from between two blond and frayed curtains. She shook like an emaciated Led Zepplin groupie dying for a cigarette as we convinced her to move us to a better connecting flight.

There was the scatty British expat with prep-school English that we met in Luxor. He’d lived his life working for the British government in Romania and was either too arrogant to be bothered with being polite or (as I gave him the benefit of the doubt) too absent-minded to notice his rudeness. At least he looked old enough to pass for absent-minded, with his thinning gray hair and comfortable paunch. Dressed in business casual with rolled back sleeves and carrying an old laptop and books, he dithered about where to sit in the reading room of the Winter Palace Hotel, trying to claim every available spot, until he finally dropped his laptop and knocked the battery out with a clatter. He hadn’t a clue as to what he’d done or how to fix it until Dad, extending remarkable courtesy and forbearance, picked things up and replaced the battery with a smile, saying , “That should do the trick, looks like there wasn’t any damage!”

This apparently meant that our new friend was honor-bound to remain with Dad for life because he was then held hostage, forced to listen to a stream of opinions on everything from the weather to the Empire to America. Lord Expat was not a fan of the Colonies, though he’d never visited.

Then there was Maurice.

Andrew and I had decided to take a sunrise hot air balloon ride over the sites of Luxor and were sitting in a boat, being ferried across the Nile to the launch site on the west bank. Across from us were two men, both black and each carrying a box of pastries and a cup of coffee from the hotel. One was completely enormous, with so much muscle and meat that his biceps and quadriceps threatened to erupt from his white v-neck t-shirt and linen pants. He topped it off with a jaunty fedora and the whole effect was so dapper–he looked terrific. His companion wore the traditional djellaba and skullcap in white and was about half the size of the other guy–that is to say, normal size.

I would have bet my life they were American. “Hi!” I said, “Where are you from?”

Big Guy looked up from his phone and said, “San Francisco.”

“Oh! What do you do there?”

He glanced at his friend and said, “I’m in broadcasting.”

I tucked that away, thinking, Hmmm–that’s vague enough to be suspicious.

“Where are you from?”

Interesting tangent: Dad is nervous enough about international travel that he swears it’s unsafe to openly admit being an American—better to let them think you’re a Canadian or something—and when people abroad ask the inevitable question, “Where you from?” He always says, “Alaska.”

Truthful. To the point. Just like Dad. He banks on the hope that other populations are as ignorant about geography as the average American (most of whom wouldn’t be able to place Alaska). However, in an odd twist of fate, the local slang for Luxor is Alaska. Which meant that when my completely oblivious yet honest American father tried his standard answer on the Egyptians they’d smiled as if to say, “Yea, pull the other one.” Or sometimes they’d say, “Welcome home” with a sarcastic smile–Egyptians love a good joke.

But Andrew and I like to live on the edge so we always answer with a cheerful, “Alaska!”

“Alaska??” he said, sitting up straighter, “That’s two!”

He paused, thinking, then said, “Hey wait--do you know Mel?”

I stared back, running through the likely scenarios and finally realizing that Big Guy had somehow met Dad, which I would have thought unlikely if I hadn’t known my Dad so well. We’d been here not yet 24 hours and already Dad was a person of interest. Who knew what would come next?

“Yea, that’s my dad,” I said tentatively.

“You’re Mel’s daughter?” And Big Guy smiled an all-teeth smile. “He’s so cool!”

I pictured my wonderful, 74 year-old father. Melvin. The one who can burp “The Stars and Stripes Forever,” who loves Consumer Reports and Craigslist, who survived the World’s Worst Attack of Kidney Stones and lived to tell the tale (over and over and over), and who recently bought a new pair of shoes that have a spring-loaded heel so that you don’t have to use a shoe-horn to put them on, combining two of his greatest loves: gadgets and footwear. I looked at Andrew and he knew what I was thinking. Are we talking about the same Mel here?

“Thanks?” I said.

“You must have been the kid in high school who had the cool dad and all your friends were jealous because your dad was so cool!”

There was that word again. I pondered this view of my dad. Again, I point out that he’s extraordinarily wonderful–both as a person and as a father–but cool? That word had never come up. It’s okay, I’m not cool either. But here was this massive human being talking to me, who had waves of coolness coming off him, who seemed to have a unique opinion of things. Is it possible to become cool just because someone who is cool declares it to be so? I chewed on this.

All through this interview Cool Guy #2 didn’t say much but when we reached our destination we all got out and were soon floating over the Valley of the Kings and Djeser-Djesu as the sun rose over the white boundary of the Nile where all life in Egypt converged in green rows of agriculture on either side of the river. Once finished, we headed back to the hotel along with the pilot and crew and we talked together easily, completely awake, as compared to our pre-dawn trip out.

“It must be nice that you’re nearly done for the day, what with the heat,” I said to our pilot, Hassan. It was Ramadan and working during the heat of the day was brutal.

He smiled. “No, I’ll go deliver a baby.”

“You mean like a doctor? You’re a doctor?”

“I’m a gyna, a gyna . . .”

“A gynecologist? An obstetrician?”

“Yes!” That was the word he was looking for. His English was excellent, but “gynecologist” was a tough one.

“So you fly balloons in the morning, and then you go deliver babies during the day?”

He nodded. What a crazy place. Ballooning had been a family business but he’d gone to medical school, had a wife and two children, and now claimed to deliver as many as 60 babies a day. I found this last part hard to believe, even with the high Egyptian birth rate, but even if there were 60 births per week we are still talking about some serious reproduction going on.

Hassan pointed to Omar, another of the pilots. “He’s a–” again, looking for the vocabulary, “A doctor but for the mouth.”

“He’s a dentist?” I said, thinking that by now it made complete sense.

“Yes, and he works with computers,” he said, pointing to another crewmember.

“A programmer?” Of course he was a programmer. Of course.

Once back at the hotel and enjoying our breakfast of chocolate crepes, strawberry juice, cucumbers, and domiati we met up with Mom and Dad who were just getting going.

“You’re not going to believe this,” I said, sitting heavily down in the upholstered chair. And I began to explain the encounter with our fellow Americans.

“Oh yea,” Dad said, with not a bit of surprise and without looking up from his phone as he scrolled through the morning news, his reader glasses slid far down to the end of his nose. “Maurice.”

“Maurice?”

“You know who he is right?” Dad was patient with my ignorance and still hadn’t looked up but Mom was now interested in the happenings. This was news to her apparently too.

“He’s Maurice Jones-Drew. He was a running back for the Jacksonville Jaguars–well, he played first for UCLA and was All-American. He can do 40 yards in 4.3. Now he works for the NFL Network.”

Broadcasting–of course! I knew it sounded suspicious. And Dad knew this guy? Maybe Maurice was more right than I’d originally thought.

Dad talks with everyone. Completely everyone and whenever he can. He approaches strangers and starts up conversations without hesitation, he coos at babies and tells little girls in frilly dresses how pretty they look. He jokes with other men about being married (though he’s been happily married for 50 years), makes dad jokes like they’re going out of style, and is unapologetically and enthusiastically the American Tourist wherever he goes. You might think he’d try to blend in, with his talk about being from Alaska, but he’s not and he doesn’t. He is a huge personality and a strong presence wherever he goes and people are usually intrigued by him and respond in a variety of ways. By the end of one day with Mom and Dad in Amalfi, our guide Salvatore swore, “I’m-a going-a to-a getta a tattoo-a of-a your-a face, Mel, to putta on-a my-a backa!”) No lie.

Apparently Dad had met Maurice in the reading room at the hotel and had struck up a conversation as he was wont to do. Maurice had noticed Dad’s enormous blue BYU ring (Dad’s hands are massive and the ring is the size of a pipe fitting) and, seeing the Y, asked if he’d gone to Yale.

“Ha! No! BYU!” Dad said proudly and after the initial introductions he’d launched into a strong opinion about BYU’s quarterback, Zach Wilson, who in the 2nd round had gone to the Jets. Apparently Maurice had just been covering the draft for the NFL Network and was impressed with Dad’s comments–did I mention that Dad’s wild about sports? He’ll say he only likes BYU football and the Braves, but I’ve never found a sport he wasn’t up on. One time I slyly tried to find a sport about which he couldn’t carry on a conversation. I failed. He may not like a sport, but he can recite the major players, stats, and latest pertinent controversies in a way that would make Google jealous.

Maurice had been thoroughly impressed with Dad’s reasoning about why the Jets are an excellent place for Wilson, to the point that I wouldn’t have been that surprised to hear that Dad would be appearing next week as the NFL Network’s surprise guest commentator with his new best buddy, MJD.

Dad is cool. Who knew?

Eleanor and Enrique were (respectively) French and Mexican octogenarians who’d been living together for 20 years and owned the premier company for luxury dahabiya cruises on the Nile. If questioned about the uniqueness of their lives, Eleanor would shrug with the haughty, effortless elegance of the French, her deep eyes carelessly glancing around her as if to say, “But of course.”

She held court on the upper deck, sitting in the shade wearing her flowing robes and large turquoise rings on her wrinkled hands that had been mellowed to a golden brown. She was normally short, but in her rattan chair propped high with cushions she seemed much taller and sat very straight, gazing back and forth as she oversaw the crew loading the last items at Esna for the week’s sail up the Nile to Aswan.

Enrique, who spoke four languages besides his native Spanish, had a large and boney, angular face with sunken eyes and large teeth. His jet-dyed hair was tied with a dirty bandana and he wore a light blue djellaba decorated with small coffee stains. He refused to wear shoes and whenever he was on land and things got particularly toasty he’d scamper from shade to shade to protect his feet, with his staff in one hand and his black hair and robes flapping. He smiled easily and enjoyed conversation with the guests and quickly found Dad to be a willing companion. Moving quickly between the two boats as we prepared to sail, he checked this and that, introduced himself to people, and looked as if he felt the same amazement and wonder as we did though he’d been sailing between Esna and Aswan for 10 years.

Together the couple managed a weekly group of 20 tourists for each boat and while Enrique oversaw the shore excursions, Eleanor seemed to be in charge of organizing guests. We’d originally booked the only two panoramic rooms on the Assouan, Nour el Nil’s oldest and least expensive ship, but when it came time to sail we were upgraded to the Agatha, the newest of the fleet. Due to COVID there were only 9 of 20 spots booked and only two ships sailing that week. The other, the Adelaide, was also at half capacity. Eleanor had moved and grouped guests, knowing through experience and her continental je ne sais quoi where each party would be most comfortable.

We arrived to find the other guests aboard the Agatha were five Millennial Parisiennes: Elsa, Joanna, Rafael, Jordan, and . . . Kevin (“Eet was a veery popular name when I was born–from Home Alone.”)

As we sat together for our initial lunch we began the customary chatter and introductions.

“Where are you from?”

“Paris,” said Elsa, the slim one who looked as if she could have passed for Audrey Hepburn with her dark-eyed, gamine face surrounded by a stylish pixie cut.

“What do you do there?”

“We produce social media content for the fashion houses’ Asian markets. Kevin and Joanna work together. Rafael has his own company. Right now I am making a short stop-action film for Lacoste.” Her voice was soft and despite her quiet confidence I sensed she was careful with her English, speaking as correctly as she could as if she were stepping on stones across a creek.

She pulled out her laptop and was happy to share the unscored film that was nearly ready.

Not having heard properly, Dad spoke up, “Who do you work for?”

“Oh many companies . . . Yves St. Laurent, Jean-Paul Gautier, Dior, Armani. . . .”

“Who’s that?” He asked, turning to Mom. So much for being cool.

But I was impressed. Awed even. On the Cool Scale, this felt even a few points ahead of our brush with the NFL.

Relationships among the Gallic group were ambiguous but Rafael and Elsa seemed to be a couple, though in a very low-key, comfortable with each other’s bodies kind of way. Joanna, taller and blond with Dutch blood, a straight neck, and a long stride, seemed to prefer listening and she worked with Kevin who was the most talkative and friendly/confident of the group. Tanned, manicured, and well-traveled, Kevin spoke the best English and claimed a Norwegian boyfriend back home in Paris–though if you’d told me that he and Elsa were together I wouldn’t have thought twice, given their intimacy. Jordan, who seemed to be the youngest and barely out of his teens, held back in a deferential way from the others. He had a high, pubescent voice, with a conspiratorial tone that could be easily heard over the others when he spoke. He was thin and hunched with an effeminate slouch, but was friendly and smiled easily.

They spent most of the week trading off the hammock, scrolling through their feeds, flipping through the latest issues of Vogue while lounging on the low couches along the deck and taking a bracing swim whenever the boat docked along the banks (all except Jordan who had a fear of water). They fit every stereotype Americans could conjure about the French–fashionable, aloof, sophisticated, and casually relaxed on principles of public nudity.

If nothing else, they were fun to watch and even more fun to talk with. We’d usually spend breakfast at separate tables prepared on deck by the crew, then come together for a joint lunch and dinner, though they often ate dinner later than we did. At first the conversation was safe, flowing through the shallow currents of “Where are you from?” “What do you do?” “What is the job like?” and “Where else have you been?” but then, as Mom and I spent our days painting while the river and reeds slipped past, they became curious and wanted to see what we were doing and began to praise and exclaim over my amateurish attempts to capture the beauty I saw.

“I would love to learn to paint!” Elsa said with sincerity though I’d seen her animation and already thought her exceptionally talented.

Kevin pulled up pictures of a friend’s work who created scarf motifs for Hermes. Yes Hermes. “Would you ever consider collaborating?” he asked and I choked a little on the “Whiskey Egyptian” that our steward Hassan had kept me supplied with since we’d set sail. Huh, collaborate. That’s cute. But regardless of the legitimacy of their ridiculous praise, I loved them for it.

But by the third day we’d all become accustomed to each other enough to feel some solidarity when it came to the other boat, which followed 100 meters downstream in our wake. During the day we might stop at a local highlight–say, the temple to Horus at Edfu, or the tombs and quarry of Gebel el-Silsilah, or the temple to Sobek and Horus at Kom Ombo–and on shore we’d mingle with the passengers from the Adelaide.

There was a stocky family of four from Montana who seemed remarkably red around the necks in their tank tops and baseball caps. The young boys were remarkably well-behaved, given the hours they were required to spend listening as our enthusiastic guide determined that his four-year degree in Egyptology would not be wasted. I was so bored I usually ditched the group to explore on my own and was grateful there was someone left listening to take one for the team.

Then there were the Norwegian thong-bearers. I wouldn’t point out such crass points of interest as their selection of underwear if it weren’t for the fact that they were so blatantly meant to be seen. Though to be fair, they had the figures to pull it off.

And rounding out the manifest was a French family consisting of a haughty, divorced mother and three teenage children: an older, curvy brunette of 18 working on the theme of “Tight and Revealing,” her younger blond sister of 16 in a mini skirt and Doc Martens, and then a brother of perhaps 15. He was at that stage where his upper lip was fuzzy and soft, his voice crackly, and his hairless legs scrawny in their basketball shorts as he awkwardly shifted from leg to leg, listening to our guide’s lectures.

At Edfu the woman stood erect in her wide-brimmed hat and large sunglasses, observing the world surreptitiously with deliberate ambivalence, and the three children hung on one another as bored teens might do. At the next glance the girls were entwined in each other’s arms, soon followed by the older one laying herself on the boy’s chest as if she were face-down on a massage table ready for a rubdown.

I had my own sunglasses and noticed the disturbing intimacy right away, and a So that’s how it is in their family! registered briefly in my thoughts. Things didn’t get any better with each shore excursion. They touched and caressed and kissed, laying their faces on each other’s chest while the mother stared into the middle distance with ennui.

At the end of the week the passengers of the Agatha came again together for our noon meal of freshly caught perch and at the far end of the table the conversation in animated French grew louder, emphasized by bursts of laughter. I focused carefully to follow the French and Else, seeing my concentration, leaned over and said, “They’re talking about the other boat!”

“The other passengers?”

“Yes, they are saying how glad they are that they are on this boat and not on the Adelaide.”

Which is something Andrew, Mom, Dad, and I had reflected on frequently during our quiet moments together but I wouldn’t have been confident enough to assume that our Parisian friends felt the same way in our poor company.

“Really?” I said, “We’ve said the same thing! The other boat seems so. . . .” I wasn’t sure how to politely finish.

“Strange? The boyfriend and girl are all over each other.” Her tone implied some disgust.

“Boyfriend? I thought that was a brother.”

“Ah, no. That is the boyfriend of the older girl. The mother and younger girl have one of the large rooms to themselves. She reserved the other large room for the other daughter and her boyfriend.”

“That’s her boyfriend?” I said again, wondering if I had missed seeing another passenger. That skinny kid with the baggy shorts? With that fully formed sexy one?

“Wow,” was all I could think to say. “I’d seen them all being creepy with each other but I thought that was just a French thing. Something cultural.”

“That is not a ‘French thing’!” Elsa retorted. “That is strange even in France!”

I laughed and said, “Well it just makes me even more glad we’re here with you instead of over there. Eleanor must have been watching us closely that first day, making sure that our rooms and companions were going to match up.”

I thought of her sitting regally in her chair, watching us all interacting that first day on the deck. She must have known exactly which of us should be together and which should be on the Adelaide. By the last night, when the crew announced after dinner that there would be dancing, then pushed back the tables and pulled out the drums and pipes, it forced even Dad to get decked out with bells and let loose with the moves. The night was so full of the fun and romance of a week on the Nile filled with pleasant company, and the men were suddenly no longer waiters and valets but musicians and dancers with amazing rhythm that we had no choice but to join in.

Most people would have put the two American groups together and then paired the French as well, but not Eleanor, she somehow knew exactly who would mix well. Though a cynic would say that the job wasn’t as hard as all that–she just took the odd jobs and stuck them on one boat and left the rest of us to ourselves. Or vice versa perhaps–who's to say who the irregulars are anyway? But regardless, she was a pretty good psychologist.

Ramadan 5 Jun 2022 11:36 AM (2 years ago)

Which is more than I can say for our cabbie, Atun, who despite looking calm and relaxed, sported sweat stains all over his short-sleeved cotton shirt as he picked us up from Cairo International Airport on an evening in early May. He was all smiles and friendliness as he loaded our luggage into the trunk, zipping us off to Zamalek while the sun hung low and deep in the reddening, smoggy sky.

Uhm Kalthum wound her way up and down the scale over the radio as we skimmed through the empty streets, windows open, so that my hair danced all over my face in the hot blast and I had to hold it back from my eyes to see the scene flying past. The hottest part of the day was just beginning to give way and the thick air made it feel as if the world were on fire.

We passed the grandstand where Anwar Sadat was assassinated, passed mosques and stadiums, past universities; the music had given way to other voices and Atun turned it up as we worked south toward the Kasr El Nile bridge and the island of Gezirah where the Cairo Tower emerged from the haze. A new voice began the azan, driving the faithful to prayer and bringing an element of familiarity.

“Do you mind if I drink?” Atun called to us with a slight bend of the head toward his shoulder.

“Of course not,” we said together and he reached for a waiting bottle of water in the console, twisted it open, and tipped his head back without taking his eyes off the road.

The end of the day, sunset, and the close of the day’s fast.

After having booked everything for our trip to Egypt with about two weeks to go I’d had the thought, When Ramadan is this year? Followed by, It can’t be now–what are the odd?

But Google doesn’t lie–there it was, Ramadan: April 12-May 12 and I had a bit of a panic. Had I messed up? What would that mean for travel? Hotels? Restaurants? I’d been around the Middle East but never during the month of fasting. I knew the basics of what Ramadan meant, but not the practicalities.

Again Mighty Google assured me that hotels and restaurants would probably still be open, with smaller places staying closing during the day, and events might close earlier than typical to accommodate the evening meal. This was accompanied by the glass-half-empty-vs.-glass-half-full statement that while some things might be closed and people might be a little grumpy (particularly toward the end of the month) we should embrace the opportunity of seeing the festivities and culture. And since our tickets were non-refundable, I chose the latter philosophy and crossed my fingers that it wouldn’t cause a problem.

That’s why we’d had such a brisk run through the streets of Cairo–no traffic. Everyone was at home ready to feast at the nightly iftar. Atun’s thirst had been the first reminder of what we could expect, and my amazement only grew as the sun rose the next day.

It had cooled to 70 during the night and breakfast on the patio of the Sofitel Nil El Gezirah was pleasant, but by 10am the heat was pressing in all around. I’d been watching the temperatures for weeks and had noticed that Cairo, which could normally expect a lovely and pleasant 85 degrees on an average May, was being hit with unseasonably warm weather. Temperatures had been well above 100 for a while and we’d be heading south to Luxor by the end of the week, where it was always warmer by 10 degrees.

I began feeling guilty at the breakfast buffet, knowing that staff were likely fasting, and my guilt only got worse as the day wore on. Whenever I’d need a drink I’d try to sneak it in on the side, like an alcoholic grabbing for a secret hip flask in a corner, wanting to be as respectful as I could–and, having fasted a few times myself, knowing how hard it can be to abstain in the right frame of mind when food and drink is all around you.

But by the time we got to Giza I’d lost most of that self-control. We went as early as we could to beat the heat, but when it’s over 100 by 9am, there’s not much to do about it. I favor the old-fashioned yet effective approach to keeping cool in intense heat: I use a jaunty umbrella to keep myself in the shade. And considering that I avoid pants and stick to loose, flowing cotton skirts it created quite the Mary Poppins effect as we strolled the empty boardwalk past giants that had been standing guard over Giza before Christ, before Moses, before Abraham.

I’d been warned about claustrophobia inside of the Great Pyramid, but it was surprisingly cool and pleasant along the slanting corridors leading to the austere tomb at the center of the Khufu’s monument. Climbing the ramps, we crept deeper and deeper into the center until we crawled through a low passageway and stood up in a chamber lit by weak florescent bulbs in the far corners. In the center lay an undecorated rectangular sarcophagus, bigger than the passageway we'd just come through. Though it was only six or so feet in length and maybe four feet high, it felt as if the entire pyramid was contained in that small space.

I apologized to the driver for my lack of self-control but he smiled. “We are used to the heat. We are used to this.” He shrugged, “You are not.”

Which well sums up how the Egyptians seemed to regard us. Americans see the news and fear the Middle East. The image of intolerance and extremism is the theme of every news hour, but it’s been my experience that people are–generally, and with great oversimplification–more tolerant of different beliefs and practices than my fellow Americans. As the United States braces itself for a new, woke era of leftist McCarthism, where people are canceled for the slightest infraction against the collective social conscious, Egyptians look at western tourists and grant them a blanket, “You Do You” pass, with no expectations that visitors live by same Islamic codes that govern their own lives. And they seem to think no less of us for it.

I didn’t realize it, but Cairo was quiet that week. The hotel had guests, but it felt empty and still. “COVID,” I’d thought. “It’s hitting everywhere.”

Then we went south to Luxor where we learned what real heat was. It’s true that it’s always 10 degrees warmer there, and the Valley of the Kings acts like a concave mirror, focusing the sun’s rays to the point that I wondered how it was that Tutankhamun hadn’t burned to ashes long ago.

How do people live here? I thought. As if people haven’t been asking that same question for thousands of years.

The apex was 114. But it was a dry heat–the kind you get when you turn your oven on.

Continuing farther south, we sailed along the Nile toward Aswan, which is where we were when Ramadan ended. The night of May 12th we were somewhere between Edfu and Gebel el Silsila, eating dinner on deck the Agatha and enjoying the sunset. Knowing that this was the last day of Ramadan I asked Hassan, our purser, “Will there be a feast for the crew tonight? For Eid al-Fatr?

“We will see,” he said. “It may not be that it is ending.”

“What?” I asked in disbelief.

“It will depend on the moon. It may be that it ends tomorrow.”

Which is how I learned of the big plot twist: You’re not guaranteed of the finish line. The local imams will watch for the new moon. If they see it, this shawwal moon, then they will declare Ramadan to be over. If not, the fasting will continue the next day and they will look for the new moon tomorrow.

Which is exactly what happened. May 12th came and went with no shawwal moon. But the next night it happened.

I first heard the sounds of celebration coming from a boat across the river and I looked up to see the sliver of light in the sky and knew what it meant. Our own crew were subdued in their enthusiasm, keeping their iftar below deck quiet and restrained, but that night they were all smiles and cheer. After the meal they pushed the tables and brought out the instruments for singing and dancing and seemed as if they were a different group of men.

And Egypt lit up.

I’d forgotten that Ramadan includes abstaining from smoking and sex and dancing as well as food and drink and with the new moon came the parties. Everyone reached for their packs of Cleopatras (yes, that is the popular brand in Egypt, I'm sure the queen would be gratified) and took a long, hard drag.

Returning to Cairo from Aswan, we stayed at the same hotel but it wasn’t the same at all. Marriages that had been delayed for Ramadan were now in full swing and the hotel was brimming with guests and bridal parties and glittering sequins. There were photo shoots and dancing and feasting like I’d never seen, with sparkling, jeweled women with dark flowing hair and men primped in western suits. All six elevators were packed every moment of the day, with people coming and going with the noise of their chatter filling the lobby.And the traffic! Everywhere cars jammed the streets. Everyone was suddenly on the move, filled with energy and things to do.

It’s as if there are three separate countries: Egypt Before, Egypt During, and Egypt After Ramadan and if you’ve only seen one, you haven’t seen it at all.

Rio the Queen 22 May 2022 9:55 AM (2 years ago)

Andrew and I have a rating system for cities. Instead of using stars we use days, meaning how many days you need for an introductory visit. What kind of a city is Boston, Fez, or Bangkok? A two day city. Madrid? Vienna? One day. Istanbul or Beijing? Solid three days. Rome? Jerusalem? Four, maybe five. Then there are the special cities–the ones where a week isn’t enough, where I could live there and never grow tired of finding new and exciting things to see and do. London. Hong Kong. Rio.

Andrew and I have a rating system for cities. Instead of using stars we use days, meaning how many days you need for an introductory visit. What kind of a city is Boston, Fez, or Bangkok? A two day city. Madrid? Vienna? One day. Istanbul or Beijing? Solid three days. Rome? Jerusalem? Four, maybe five. Then there are the special cities–the ones where a week isn’t enough, where I could live there and never grow tired of finding new and exciting things to see and do. London. Hong Kong. Rio.

What makes these special? Hmmm . . . well, start with the energy of the place. These are cities that have a vitality other places lack. Some would argue New York has it and I suppose so but just having movement–or in New York’s case, a good dose of attitude–doesn’t count. On the streets of London you feel excitement and motion in the theater, the cockney, the cheekiness; in Hong Kong it’s encapsulated in the lights–everywhere the lights–and soaring verticality. In Rio it’s the rhythm of the waves on the beach mixed with the samba of the dance and the tropical colors.

These are the cities where there’s not only monuments, castles, statues, ruins, or historic sites to tour, there’s places you need to stand in to find scope. In Hong Kong you have to ride to the top of Victoria Peak or be on the deck of the Star Ferry to see the city properly. In Rio it’s Sugarloaf Mountain and Corcovado for that perspective.

We’d planned on taking the Trem do Corcovado to see the Cristo Redentor statue but left the day open to accommodate the weather. With the possibility of rain I didn’t want to go when we’d be fogged in. When we woke up on Thursday morning March 10th the sky was brilliant and clear, so after breakfast on the 15th floor of the Ritz Copacabana we grabbed a cab and worked our way through the mid-morning traffic counter clockwise around Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas and over to the edge of Tijuaca National Park where the station lay.

The heat was coming on but not yet strong enough to really wilt us and we stood in the shade waiting for the tram. Once seated the heat became harder until the car moved and circulated the air currents through the open windows as we headed up the mountain, held firmly against the backs of our seats by the steep incline. On the hillside the forest was thick, with semi-isolated houses and wandering dogs but once at the top we could see the city from all sides, laid out for us, as we climbed the remaining way up the stairs to the feet of the statue.

I had planned on visiting Cristo Redentor of course but I wasn’t prepared for the experience. I’ve seen the Statue of Liberty, the Great Wall of China, the great pyramids of Giza and all are inspiring but this is different. On the top of Corcovado Mountain (meaning “Where is my heart going?”) the 125 foot resurrected Savior stretches out his hands to His people, offering them the protection He describes when He says, “How oft would I have gathered you as a hen gathererth her chickens!” This isn’t the usual Christ in agony on the cross, twisted and distorted with suffering, emaciated and effeminate, this is the risen Lord in glory presenting Himself as a ransom for sin. I felt tears in my eyes as I stood in the shadow, taking it in and yet watching the masses of people milling about–some looking for their photo op for Instagram, some selling beach towels and other souvenirs, most stretching out their arms in an ignorant imitation as their friends took pictures. One woman wore an black t-shirt that shouted, “RELIGIO SIDADE MATA” (religiosity kills) while she and her family took turns snapping selfies in front of the statue. I wanted to ask her if she had planned on being ironic or merely offensive when she got dressed that morning.

The Eiffel Tower or the Colosseum is impressive, some think it beautiful, but it doesn’t have the power to inspire that kind of feeling when you visit.

There are lots of cities where you can find fun things to do–Los Angeles has its theme parks and entertainment industry, Bangkok has canal tours, Buenos Aires can teach you to tango but like Rio’s colorful markets with stacks of fruits you’ve never seen before, only in these super cities is there so much variety.

As I’d planned our trip to Rio our time there stretched as my list of things to do grew. Rio has the largest urban green space in the world–Tijuaca Park–and the trails give you access to waterfalls, marmosets, capuchin monkeys, sloths, and coatis. You can hike on Sugarloaf and if you still want more there are day trips just outside the city–such as to Ilha Grande, also great for snorkeling and diving and beaches.

There’s Paqueta Island, accessible by a 45 minute ferry, or Niteroi across the bridge. There’s Petropolis for another nearby day trip and a bit of colonial history, or any of the beaches–Sao Conrado, Leblon, Ipanema, Copacabana, or Flamengo– and those are just the main ones. There’s Maracana Stadium and the Sambadromo for football and celebrations and concerts, then there’s Jardim Botanico, the most beautiful botanical gardens I’ve ever seen.

Monday March 14 found us driving to the top of Pedra Bonita with our guide Daniel and his friend Carlos who suited us up for tandem paragliding down to Sao Conrado beach below. Andrew went first with Carlos and I followed with Daniel. I’d pictured jumping off a cliff, but instead we drove to the top, parked in the parking lot and walked to a covered set of bleachers built into the side. Before us was a slanted platform steep enough to make you watch your step on the non-slip turf and the idea was that, once ready, you’d simply walk off the edge.

Daniel had me try a practice walk across the platform, saying the key was to walk firmly and confidently, pulling hard enough against the sail strapped to your shoulders to allow the air to catch it and lift it, pulling you into the air before you actually stepped off the edge. That’s all great in theory but when it comes time to actually do it, somehow it seems easier to close your eyes and jump rather than to march forward without hesitation to the edge of a cliff then take a step into the air.

Well I suppose if this kills me it won’t matter if I jump or walk calmly or rush off to my death. Falling is falling so I might as well fake confidence and do my best.

Sure enough, as I pushed forward toward the edge, Daniel strapped behind me and matching my footsteps, I felt the sail inflate and rise as if it was a set of lungs filling with a single breath of air. By the time I reached the edge my feet had left the ground and I was floating–hanging slightly awkwardly off the edge of my seat, but floating. I raised my knees to my chest in order to scoot myself back in the harness, all the while holding the stupid selfie stick that they’d insisted I carry.

Immediately we caught an updraft and began to rise. Daniel had an altimeter strapped to his shoulder that beeped as we rose. The faster we rose the faster it beeped so that as we caught the strength of the updraft and pushed higher and higher, spiraling into the sky it beeped as if time were running out on a bomb.

When we’d rode the current higher than the surrounding mountains, with the other paragliders far below us, Daniel directed us out over the water which made me more nervous than before. I knew it made no sense–falling is falling and whether I’d hit the trees, the rocks, the water, or the buildings I’d be doomed–but somehow it felt more precarious being far out over the water, as if we could blow out over the Atlantic, never to be found.

“Here, you steer!” Daniel said, and handed the command lines over to me. We had not discussed this. I gripped them in horror–what if I accidentally let go? The handle would fly up out of reach and we’d lose control and die. How could he have been so stupid as to entrust something so critical to a terrified newbie like me? I clung to the handles, barely hearing what he was saying, until I finally pulled on the right handle and felt our position tilt. I steered right, then left, getting a feel for the turn and the responsiveness. Then the thrill seeped in–the excitement of controlling something that controlled me–and I realized how someone could spend every weekend doing this over and over again.

When we’d first planned our South America trip many people said, “Oh be careful! It’s dangerous!” This wasn’t unusual, any time we’ve visited a place not in Europe we’ve had people suggest that we would most definitely die and then seemed surprised when we came back in one piece. But Americans just don’t get a good version of reality from watching television–the news highlights the extremes, the unusual, and the horrors without balancing it with the average or the mundane. And if something extreme does happen, a serious event triggers increased security and caution (and better prices) because everyone wants to be that safe place where tourists want to visit. No one wants tourists to go home and tell their friends not to visit Country X because they got mugged and left for dead. In fact, the only time I’ve had anything close to a security issue was when, in Egypt, the police were so cautious of protecting American tourists that they pulled over our driver for being lazy and not filing the proper paperwork showing that he was carrying such precious cargo.

“I have a bad feeling about this!” said a friend of mine when we described our trip to Buenos Aires, Iguazu Falls, and Rio de Janeiro. I wanted to point out that if her feeling was truly a warning, that it would have been more efficient to warn the person buying the tickets (i.e. me) rather than to trust the message to a third party delivery service. Then I wanted to let her know that every time I get into an airplane I have a horrible feeling that this might be it and that this is the flight where our number is up and we might crash. The anxiety doesn’t get too far because I’m a numbers gal and believe in playing the odds–there hasn’t been an airline disaster in decades–but heaven forbid something actually does happen, it doesn’t prove causality. Besides, no one ever thinks, when they return safely, Well, that nasty feeling that I thought was a premonition obviously wasn’t accurate. Maybe those feelings I get are just my nerves, I should take note of this for the future.

But this trip to Rio had me on a low level of alert. I do a lot of research prior to a trip. It doesn’t matter where we go, the The State Department will say that it’s dangerous and that we should rethink things. It is easier to put this into perspective when you hear that the UK likewise warns its citizens about travel to the U.S. Dangerous?? It’s dangerous to travel here? How? Well if you look at the random everyday things that routinely happen across the country, taken cumulatively they add up to a big fat “Do Not Go There It’s Dangerous” label for nervous Europeans. Every city in the world has places you shouldn’t go after dark; it’s always dangerous to go out drinking late at night, especially alone, especially for women; and no one should ever flash money around on the street like a moron begging to be mugged.

With other cities we’ve visited I haven't seen average travelers or expats giving out warnings–but that was different with Rio where people online routinely warned against certain behaviors or areas. Not in a hugely significant way but with enough earnestness to make me determined to not be stupid. I wasn’t quite sure what to expect.

But Rio was lovely! Sweet smelling and cheerful, it was cleaner than most cities, with people out every morning sweeping the lovely tiled sidewalks that sported different black and tan patterns depending on the neighborhood. No trash, no feral cats, no drunks on the sidewalk, in short a charming and beautiful place.

"Be careful of the beaches!" We’d been particularly warned about these but Copacabana is wide and clean and carefully patrolled by police officers, particularly as the sun gets low. At night it’s well lit with huge stadium lights and the famous boardwalk feels as safe as any other big city–just watch your bags and keep yourself on guard and you should be fine.

Of course, we didn’t take any of those dreadful tours into the favelas where rich tourists gawk at the locals, we stuck to the major areas and arteries, didn’t go out late at night, and never frequented bars or clubs. So within those parameters we felt completely safe and enjoyed ourselves thoroughly.

I didn’t expect it, we went on a whim because it was one of the few places to go where it was warm in March, but couldn’t have dreamed we’d find so much fun there. Definitely one of the best.

Sketches from Argentina 12 May 2022 2:22 PM (2 years ago)

Buenos Aires and Puerto Iguazu - March 1-9, 2022

Sketches from Rio 12 May 2022 2:22 PM (2 years ago)

Didn't See That Coming 30 Apr 2022 8:23 PM (2 years ago)

I convince myself that I’m flexible by not binding myself to a certain activity on a specific day generally, telling myself that I’m just planning guidelines and if we wake up and feel to do something different then we can change it up. I make lists three months before we leave, and one month, and the week of departure. I make packing lists and lists of places to get hot chocolate wherever we’ll be. I make lists of the best bakeries, of must-eat local delicacies, of sporting events and festivals, of beaches, and even rocks and minerals that I might find (I’m a bona fide rock hound).

So to say that I got caught short in Argentina is like saying I got hit by lightning. At least that’s how I like to think of it.

Years back I decided it was easier to get currency within our destination, at local ATMs. Our bank waives all fees and gives a better rate of exchange than other places. If I order currency before the trip at our corner branch they’ll charge me for delivery and then again for any unused bills I want to cash back in. I learned all of this when traveling to Morocco, which controls its currency so tightly that you can’t get dirhams outside of the country. Pre-ordering was impossible and it worked fine to just use airport ATMs on arrival.

As we were packing for a trip to South America Andrew mentioned that he thought he’d bring $100 cash.

“If you think you need it,” I said and then added, thinking of pickpockets and other security risks, “Though we’ll just get money when we’re there–it might just be a pain to carry it.” He felt better having something in his pocket–and since I usually carry all currency it probably made him feel like a grown up having his own bills on hand.

Touching down in Buenos Aires we got our luggage and just as we were about to flag our ride I remembered, “Oh we’ve got to stop at the ATM!”

It took a bit to find it tucked away behind the McDonalds, but we inserted our debit card and went through all the mental calculations to figure how much we needed to withdraw.

“Five thousand pesos?” I asked, “Sound good? I mean we’ll need more but that ought to do for a bit. I think that’s about $50.”

We took the cash and headed for the exit, rolling our luggage behind us.

We checked into our hotel on Tucuman Street south of the Palermo neighborhood, greeted by a friendly woman who spoke little English but with Andrew’s limited Spanish we somehow got along.

“Will we pay now or at the end?” I asked, seeing that it was a small operation, nearly like an Airbnb.

“Cash now,” she said. “U.S. Dollars.”

I blinked, “Dollars? We didn’t bring dollars–I didn’t know you wanted them.”

She indicated some of the local ATMs would dispense dollars and suggested a few places nearby, unworried that we couldn’t pay upfront. “We are like family!” She said with a smile. I smiled back but was uncomfortable. I didn’t like having outstanding bills. We’d have to get cash right quick and get her paid.

We stashed our luggage, rested up a bit, then headed out to see the town, pointing ourselves towards Recoleta and the central landmarks. We took our time at Plaza San Martin and wandered the famous Recoleta Cemetery–a city within the city where crypts lined tiny avenues and statues of weeping cherubs and veiled widows gazed dejectedly down, streaked and gray, against the pale blue sky. We followed the parks north to Narda Comedor and enjoyed the best and messiest avocado sandwich I’d ever hoped to have until the jetlag caught up with us and we hailed a cab to get us home.

I hadn’t forgot the money thing and stopped at a Santander kiosk. I inserted my card, went through all the prompts, and the computer began to process my request. We stared at the spinning icon, waiting, waiting, until we began to wonder what was wrong. I canceled the transaction and tried again. And again. Then we tried the machine next to ours. A woman came in and, trying not to freak her out by looking as if we were stalking her, watched as she went through her own transaction successfully.

“Well she got cash,” Andrew said, “So it’s not the machine I guess.”

We wandered and found another ATM and tried again, all with similar results.

“This is so weird,” I said. “It’s not the card, I haven’t got any notice from the bank and it worked fine this morning at the airport. It’s like their network has problems or something.”

“This is so weird,” I said. “It’s not the card, I haven’t got any notice from the bank and it worked fine this morning at the airport. It’s like their network has problems or something.”

Just to be safe I called our bank. Was there anything wrong with our debit card? Had there been an error somewhere? I’d put travel alerts on the account.

No, the card was fine. The bank showed us getting cash that morning and nothing else. Nothing denied, no problems.

The next morning I decided we had to get aggressive and get cash first thing. We went down the road to the banking district, conveniently just down the street from us. The banks were just beginning to open and I went inside the entry to the ATM and inserted my card. All with the same result, only this time with the prompt, “You’ve exceeded your limit.”

What? Our daily limit was nearly $500, we had plenty of room still–what was going on?

I went inside to speak with a teller. English was again a problem (something we’d come to learn during the trip) and our Spanish was weak–especially given the extravagant Argentine accent that made Spanish sound more like Portuguese. They found someone who could speak English and the nice woman suggested just what the machine had–that we’d reached our limit. Sorry, not their problem. Check with your bank.

I explained we already had and that the bank insisted–and I knew it to be true–that we hadn’t come close to our limit. We were fine, it wasn’t on our end. What was going on? Besides, we hadn’t withdrawn any cash that day so how could we have hit a daily limit?

She was apologetic but hadn’t a clue what was going on, any more than we did. She ended by offering her personal cell number and said we could call if we needed anything more, which surprised me. We were strangers–her personal cell number? That seemed more than the situation deserved but it left us without options and we left, determined to find another ATM.

After another failure I gave up, not sure what to do.

That night I spoke with our hostess and told her our problem, or as much of it as I could convey with the language barrier.

She nodded energetically. “Yes, yes. That is right, there is a limit on how many pesos you can have.”

Confused, we asked her for clarification.

Argentina has money problems. Big money problems–inflation being just one part of a convoluted mess that has led to its citizens distrusting the currency. With the wide fluctuations people have turned to the dollar, and even more the Euro, preferring to not have their buying power depleted. Credit card fees and online exchange rates have made credit cards a problem for some–such as our hotel owner–so many have turned to cash-only transactions. In answer to this and other problems, the government has tried to control the flow by putting a cap on the amount of cash floating around, setting daily limits on the number of pesos that banks can give out. At that moment the cap was 5000 pesos per day. Since we had withdrawn (by coincidence) 5000 pesos at the airport at 9am Thursday we wouldn’t be able to take out any more until at least Friday morning 9am. We’d been trying all Thursday and early Friday.

Then, to add more of a twist to this crazy plot, people were so desperate for cash, given the monetary issues they were facing, that they would often withdraw cash immediately each day, leaving machines empty by the afternoon–don’t even think about getting anything out on Friday evening when you drew your paycheck.

As I grasped the situation and the implications began to sink in I wanted to whistle. Wow. Just wow. I had no idea–I mean, I’d heard years back about Argentina having problems in that vein, but I didn’t think it had evolved to this.

So there we were, wondering how we were going to make good on our debt with only being able to withdraw the equivalent of $50 in pesos each day? We had $100, but still needed another $150 approximately, and that didn’t include what it would take to do the things we’d planned.

How could we get more cash?

It’s actually an interesting question, really. America runs on credit and I don’t carry cash. Checks have become obsolete, it’s all electronic. We turned to things like Western Union but ruled out getting family members back home involved. We settled on Xoom, a way to wire yourself money and thought that seemed our best bet. Oh how naive we were! We went through all the screens, filled out the fields, pushed the “send” button and headed down to the bank on the corner to collect the money.

It’s actually an interesting question, really. America runs on credit and I don’t carry cash. Checks have become obsolete, it’s all electronic. We turned to things like Western Union but ruled out getting family members back home involved. We settled on Xoom, a way to wire yourself money and thought that seemed our best bet. Oh how naive we were! We went through all the screens, filled out the fields, pushed the “send” button and headed down to the bank on the corner to collect the money.

When we got there and said we were there to pick up our transfer they just looked at us like we were crazy. Cash? You want cash?

It hit me how stupid I was. Wiring money to yourself is only as good as the cash reserves available. The money might be in the vaults back home, but unless they had the cash at the receiving end the whole thing was useless. Friday evening? Cash? Yea, right. You’ve got to be kidding. They had nothing–hadn’t had pesos all day.

Walking home we started to panic a bit. What were we going to do? We tallied up what we had left. Forget paying our hotel bill, how were we going to get to the airport and through our next leg? We wouldn’t be leaving Argentina for nearly a week and had a couple high cost stops ahead, we’d be stranded. It felt as if we were in an episode of The Amazing Race. And about to get eliminated.

Buenos Aires is clean and neat–truly “Good Breezes” is the perfect name for it–but it was then I started to notice people on the corners. They didn’t appear to be begging exactly–they looked too clean and put together to be begging–what were they doing? As we passed they all seemed to be chanting the same thing. “Cambio . . . cambio . . . cambio” usually with outstretched hands and fanny packs open around their waists.

They weren’t homeless, and they weren’t begging the way you’d see other places, they seemed to be asking for cash. So yes, begging, but not destitute. Maybe it was to make rent until they could cash their check on Monday, who knows? That seemed to explain the situation best and it left me kind of sheepish. It was the first time when I’d seen panhandlers and thought, “Yea, I hear you–I need cash too!”