Explaining Cloud-9: A Celestial Object Like No Other 7 Jan 3:55 AM (4 days ago)

Some three years ago, the Five-Hundred Meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST) in Guizhou, China discovered a gas agglomeration that was later dubbed Cloud-9. It’s a cute name, though unintentionally so, as this particular cloud is simply the ninth thus far identified near the spiral galaxy Messier 94 (M94). And while gas clouds don’t particularly call attention to themselves, this one is a bit of a stunner, as later research is now showing. It’s thought to be a gas-rich though starless cloud of dark matter, a holdover from early galaxy formation.

Scientists are referring to Cloud-9 as a new type of astronomical object. FAST’s detection at radio wavelengths has been confirmed by the Green Bank Telescope and the Very Large Array in the United States. The cloud has now been studied by the Hubble telescope’s Advanced Camera for Surveys, which revealed its complete lack of stars. That makes this an unusual object indeed.

Alejandro Benitez-Llambay (Milano-Bicocca University, Milan) is principal investigator of the Hubble work and lead author of the paper just published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The results were presented at the ongoing meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Phoenix. Says Benitez-Llambay:

“This is a tale of a failed galaxy. In science, we usually learn more from the failures than from the successes. In this case, seeing no stars is what proves the theory right. It tells us that we have found in the local Universe a primordial building block of a galaxy that hasn’t formed.”

Here there’s a bit of a parallel with our recent discoveries of interstellar objects moving through our Solar System. In both cases, we are discovering a new type of object, and in both cases we are bringing equipment online that will, in relatively short order, almost certainly find more. We get Cloud-9 through the combination of radio detection via FAST and analysis by the Hubble space telescope, which was able to demonstrate that the object does lack stars.

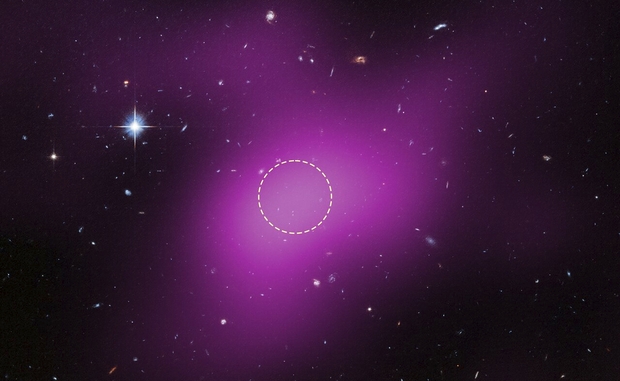

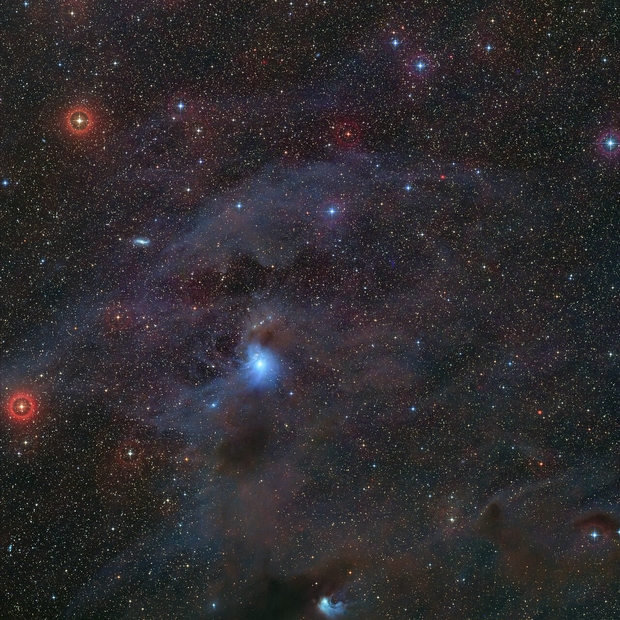

Image: This image shows the location of Cloud-9, which is 14 million light-years from Earth. The diffuse magenta is radio data from the ground-based Very Large Array (VLA) showing the presence of the cloud. The dashed circle marks the peak of radio emission, which is where researchers focused their search for stars. Follow-up observations by the Hubble Space Telescope’s Advanced Camera for Surveys found no stars within the cloud. The few objects that appear within its boundaries are background galaxies. Before the Hubble observations, scientists could argue that Cloud-9 is a faint dwarf galaxy whose stars could not be seen with ground-based telescopes due to the lack of sensitivity. Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys shows that, in reality, the failed galaxy contains no stars. Credit: Science: NASA, ESA, VLA, Gagandeep IAnand (STScI), Alejandro Benitez-Llambay (University of Milano-Bicocca); Image Processing: Joseph DePasquale (STScI).

We can refer to Cloud-9 as a Reionization-Limited H Ι Cloud, or RELHIC (that one ranks rather high on my acronym cleverness scale). H I is neutral atomic hydrogen, the most abundant form of matter in the universe. The paper formally defines RELHIC as “a starless dark matter halo filled with hydrostatic gas in thermal equilibrium with the cosmic ultraviolet background.” This would be primordial hydrogen from the earliest days of the universe, the kind of cloud we would normally expect to have become a ‘conventional’ spiral galaxy.

The lack of stars here leads co-author Rachael Beaton to refer to the object as an ‘abandoned house,” one which likely has others of its kind still awaiting discovery. In comparison with the kind of hydrogen clouds we’ve identified near our own galaxy, Cloud-9 is smaller, certainly more compact, and unusually spherical. Its core of neutral hydrogen is measured at roughly 4900 light years in diameter, with the hydrogen gas itself about one million times the mass of the Sun. The amount of dark matter needed to create the gravity to balance the pressure of the gas is about five billion solar masses. While the researchers do expect to find more such objects, they point out that ram pressure stripping can deplete gas as any cloud moves through the space between galaxies. In other words, the population of objects like RELHIC is likely quite small.

The paper places the finding of Cloud-9 in context within the framework now referred to as Lambda Cold Dark Matter (ACDM), which incorporates dark energy via a cosmological constant into a schemata that includes dark matter and ordinary matter. Quoting the paper’s conclusion:

In the ΛCDM framework, the existence of a critical halo mass scale for galaxy formation naturally predicts galaxies spanning orders of magnitude in stellar mass at roughly fixed halo mass. This threshold marks a sharp transition at which galaxy formation becomes increasingly inefficient (A. Benitez-Llambay & C. Frenk 2020), yielding outcomes that range from halos entirely devoid of stars to those able to form faint dwarfs, depending sensitively on their mass assembly histories. Even if Cloud-9 were to host an undetected, extremely faint stellar component, our HST observations, together with FAST and VLA data, remain fully consistent with these theoretical expectations. Cloud-9 thus appears to be the first known system that clearly signals this predicted transition, likely placing it among the rare RELHICs that inhabit the boundary between failed and successful galaxy formation. Regardless of its ultimate nature, Cloud-9 is unlike any dark, gas-rich source detected to date.

The paper is Gagandeep et al., “The First RELHIC? Cloud-9 is a Starless Gas Cloud,” The Astrophysical Journal Letters, Volume 993, Issue 2 (November 2025), id.L55, 7 pp. Full text.

Astrobiology: What Our Planet Can Teach Us 1 Jan 5:25 AM (10 days ago)

Will 2026 be the year we detect life elsewhere in the universe? The odds seem against it, barring a spectacular find on Mars or an even more spectacular SETI detection that leaves no doubt of its nature. Otherwise, this new year will continue to see us refining large telescopes, working on next generation space observatories, and tuning up our methods for biosignature detection. All necessary work if we are to find life, but no guarantee of future success.

It is, let’s face it, frustrating for those of us with a science fictional bent to consider that all we have to go on is our own planet when it comes to life. We are sometimes reminded that an infinite number of lines can pass through a single point. And yes, it’s true that the raw materials of life seem plentiful in the cosmos, leading to the idea that living planets are everywhere. But we lack evidence. We have exactly that one datapoint – life as we know it on our own planet – and every theory, every line we run through it is guesswork.

I got interested enough in the line and the datapoint quote that I dug into its background. As far as I can find, Leonardo da Vinci wrote an early formulation of a mathematical truth that harks back to Euclid. In his notebooks, he says this:

“…the line has in itself neither matter nor substance and may rather be called an imaginary idea than a real object; and this being its nature it occupies no space. Therefore an infinite number of lines may be conceived of as intersecting each other at a point, which has no dimensions…”

It’s not the same argument, but close enough to intrigue me. I’ve just finished Jon Willis’ book The Pale Blue Data Point (University of Chicago Press, 2025), a study addressing precisely this issue. The title, of course, recalls the wonderful ‘pale blue dot’ photo taken from Voyager 1 in 1990. Here Earth itself is indeed a mere point, caught within a line of scattered light that is an artifact of the camera’s optics. How many lines can we draw through this point?

We’ve made interesting use of that datapoint in a unique flyby mission. In December, 1990 the Galileo spacecraft performed the first of two flybys of Earth as part of its strategy for reaching Jupiter. Carl Sagan and team used the flyby as a test case for detecting life and, indeed, technosignatures. Imaging cameras, a spectrometer and radio receivers examined our planet, recording temperatures and identifying the presence of water. Oxygen and methane turned up, evidence that something was replenishing the balance. The spacecraft’s plasma wave experiment detected narrow band emissions, strong signs of a technological, broadcasting civilization.

Image: The Pale Blue Dot is a photograph of Earth taken Feb. 14, 1990, by NASA’s Voyager 1 at a distance of 3.7 billion miles (6 billion kilometers) from the Sun. The image inspired the title of scientist Carl Sagan’s book, Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space, in which he wrote: “Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us.” NASA/JPL-Caltech.

So that’s a use of Earth that comes from the outside looking in. Philosophically, we might be tempted to throw up our hands when it comes to applying knowledge of life on Earth to our expectations of what we’ll find elsewhere. But we have no other source, so we learn from experiments like this. What Willis wants to do is to look at the ways we can use facilities and discoveries here on Earth to make our suppositions as tenable as possible. To that end, he travels over the globe seeking out environs as diverse as the deep ocean’s black smokers, the meteorite littered sands of Morocco’s Sahara and Chile’s high desert.

It’s a lively read. You may remember Willis as the author of All These Worlds Are Yours: The Scientific Search for Alien Life (Yale University Press, 2016), a precursor volume of sorts that takes a deep look at the Solar System’s planets, speculating on what we may learn around stars other than our own. This volume complements the earlier work nicely, in emphasizing the rigor that is critical in approaching astrobiology with terrestrial analogies. It’s also a heartening work, because in the end the sense of life’s tenacity in all the environments Willis studies cannot help but make the reader optimistic.

Optimistic, that is, if you are a person who finds solace and even joy in the idea that humanity is not alone in the universe. I certainly share that sense, but some day we need to dig into philosophy a bit to talk about why we feel like this.

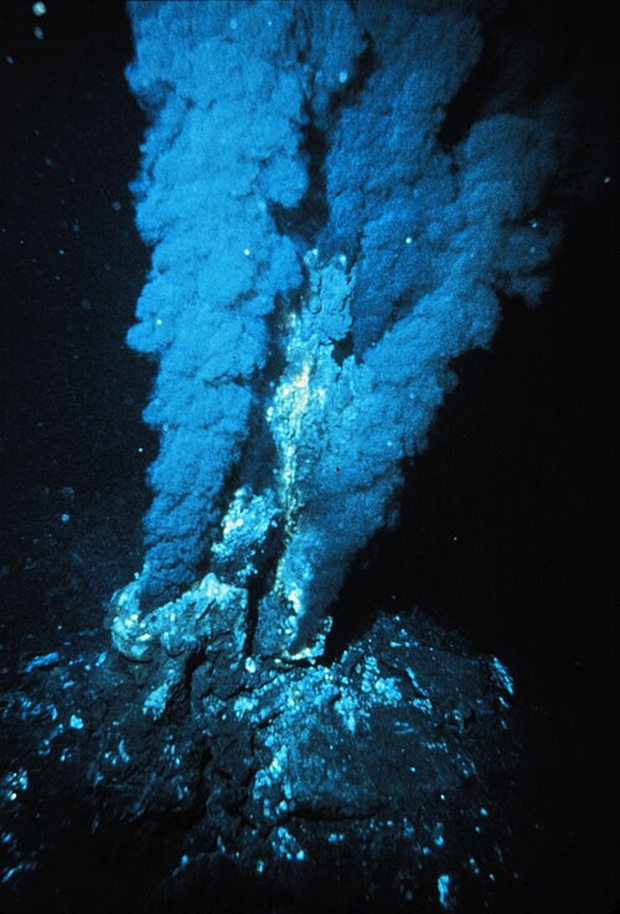

Willis, though, is not into philosophy, but rather tangible science. The deep ocean pointedly mirrors our thinking about Europa and the now familiar (though surprising in its time) discovery by the Galileo probe that this unusual moon contained an ocean. The environment off northwestern Canada, in a region known as the Juan Fuca Plate, could not appear more unearthly than what we may find at Europa if we ever get a probe somehow underneath the ice.

The Endeavor hydrothermal vent system in this area is one of Earth’s most dramatic, a region of giant tube worms and eyeless shrimp, among other striking adaptations. Vent fluids produce infrared radiation, an outcome that evolution developed to allow these shrimp a primitive form of navigation.

Image: A black smoker at the ocean floor. Will we find anything resembling this on moons like Europa? Credit: NOAA.

Here’s Willis reflecting on what he sees from the surface vessel Nautilus as it manages two remotely operated submersibles deep below. Unfolding on its computer screens is a bizarre vision of smoking ‘chimneys’ in a landscape he can only describe as ‘seemingly industrial.’ These towering structures, one of them 45 feet high, show the visual cues of powering life through geological heat and chemistry. Could a future ROV find something like this inside Europa?

It is interesting to note that the radiation produced by hydrothermal vents occurs at infrared wavelengths similar to those produced by cool, dim red dwarf stars such as Proxima Centauri, the closest star to our Sun and one that hosts its own Earth-sized rocky planet. Are there as yet any undiscovered terrestrial microbes at hydrothermal vents that have adapted the biochemistry of photosynthesis to exploit this abundant supply of infrared photons in the otherwise black abyss? Might such extreme terrestrial microbes offer an unexpected vision of life beyond the solar system?

The questions that vistas like this spawn are endless, but they give us a handle on possibilities we might not otherwise possess. After all, the first black smokers were discovered as recently as 1979. Before that, any hypothesized ocean on an icy Jovian moon would doubtless have been considered sterile. Willis goes on:

It is a far-out idea that remains speculation — the typical photon energy emitted from Proxima Centauri is five times greater than that emerging from a hydrothermal vent. However, the potential it offers us to imagine a truly alien photosynthesis operating under the feeble glow of a dim and distant sun makes me reluctant to dismiss it without further exploration of the wonders exhibited by hydrothermal vents.

We can also attack the issue of astrobiology through evidence that comes to us from space. In Morocco, Willis travels with a party that prospects for meteorites in the desert country that is considered prime hunting ground because meteorites stand out against local rock. He doesn’t find any himself, but his chapter on these ‘fallen stars’ is rich in reconsideration of Earth’s own past. For just as some meteorites help us glimpse ancient material from the formation of the Solar System, other ancient evidence comes from our landings at asteroid Ryugu and Bennu, where we can analyze chemical and mineral patterns that offer clues to the parent object’s origins.

It’s interesting to be reminded that when we find meteorites of Martian origin, we are dealing with a planet whose surface rocks are generally much older than those we find on Earth, most of which are less than 100 million years old. Mars by contrast has a surface half of which is made up of 3 billion year old rocks. Mars is the origin of famous meteorite ALH84001, briefly a news sensation given claims for possible fossils therein. Fortunately our rovers have proven themselves in the Martian environment, with Curiosity still viable after thirteen Earth years, and Perseverance after almost five. Sample return from Mars remains a goal astrobiologists dream about.

Are there connections between the Archean Earth and the Mars of today? Analyzing the stromatolite fossils in rocks of the Pilbara Craton of northwest Australia, the peripatetic Willis tells us they are 3.5 billion years old, yet evidence for what some see as cyanobacteria-like fossils can nonetheless be found here, part of continuing scientific debate. The substance of the debate is itself informative: Do we claim evidence for life only as a last resort, or do we accept a notion of what early life should look like and proceed to identify it? New analytical tools and techniques continue to reshape the argument.

Even older Earth rocks, 4 billion years old, can be found at the Acasta River north of Yellowknife in Canada’s Northwest Territories. Earth itself is now estimated to be 4.54 billion years old (meteorite evidence is useful here), but there are at least some signs that surface water, that indispensable factor in the emergence of life as we know it, may have existed earlier than we thought.

We’re way into the bleeding edge here, but there are some zircon crystals that date back to 4.4 billion years, and in a controversial article in Nature from 2001, oceans and a continental crust are argued to have existed at the 4.4 billion year mark. This is a direct challenge to the widely accepted view that the Hadean Earth was indeed the molten hell we’ve long imagined. This would have been a very early Earth with a now solid crust and significant amounts of water. Here’s Willis speculating on what a confirmation of this view would entail:

Contrary to long-standing thought, the Hadean Earth may have been ‘born wet; and experienced a long history of liquid water on its surface. Using the modern astrobiological definition of the word, Earth was habitable from the earliest of epochs. Perhaps not continuously, though, as the Solar System contained a turbulent and violent environment. Yet fleeting conditions on the early Earth may have allowed the great chemistry experiment that we call life to have got underway much earlier than previously thought.

We can think of life, as Willis notes, in terms of what defines its appearance on Earth. This would be order, metabolism and the capacity for evolving. But because we are dealing with a process and not a quantity, we’re confounded by the fact that there are no standard ‘units’ by which we can measure life. Now consider that we must gather our evidence on other worlds by, at best, samples returned to us by spacecraft as well as the data from spectroscopic analysis of distant atmospheres. We end up with the simplest of questions: What does life do? If order, metabolism and evolution are central, must they appear at the same time, and do we even know if they did this on our own ancient Earth?

Willis is canny enough not to imply that we are close to breakthrough in any area of life detection, even in the chapter on SETI, where he discusses dolphin language and the principles of cross-species communication in the context of searching the skies. I think humility is an essential requirement for a career choice in astrobiology, for we may have decades ahead of us without any confirmation of life elsewhere, Mars being the possible exception. Biosignature results from terrestrial-class exoplanets around M-dwarfs will likely offer suggestive hints, but screening them for abiotic explanations will take time.

So I think this is a cautionary tone in which to end the book, as Willis does:

…being an expert on terrestrial oceans does not necessarily make one an expert on Europan or Enceladan ones, let alone any life they might contain. However…it doesn’t make one a complete newbie either. Perhaps that reticence comes from a form of impostor syndrome, as if discovering alien life is the minimum entry fee to an exclusive club. Yet the secret to being an astrobiologist, as in all other fields of scientific research, is to apply what you do know to answer questions that truly matter – all the while remaining aware that whatever knowledge you do possess is guaranteed to be incomplete, likely misleading, and possibly even wrong. Given that the odds appear to be stacked against us, who might be brave enough to even try?

But of course trying is what astrobiologists do, moving beyond their individual fields into the mysterious realm where disciplines converge, the ground rules are uncertain, and the science of things unseen but hinted at begins to take shape. Cocconi and Morrison famously pointed out in their groundbreaking 1959 article launching the field of SETI that the odds of success were unknown, but not searching at all was the best way to guarantee that the result would be zero.

We’d love to find a signal so obviously technological and definitely interstellar that the case is proven, but as with biosignatures, what we find is at best suggestive. We may be, as some suggest, within a decade or two of some kind of confirmation, but as this new year begins, I think the story of our century in astrobiology is going to be the huge challenge of untangling ambiguous results.

Building a Library of Science Fiction Film Criticism 19 Dec 2025 9:28 AM (23 days ago)

Back in the days when VCR tapes were how we watched movies at home, I took my youngest son over to the nearby Blockbuster to cruise for videos. He was a science fiction fan and tuned into both the Star Trek and Star Wars franchises, equally available at the store. But as he browsed, I was delighted to find a section of 1950s era SF movies. I hadn’t realized until then how many older films were now making it onto VCR, and here I found more than a few old friends.

Films of the black and white era have always been a passion for me, and not just science fiction movies. While the great dramas of the 1930s and 40s outshone 1950s SF films, the latter brought the elements of awe and wonder to the fore in ways that mysteries and domestic dramas could not. The experience was just of an entirely different order, and the excitement always lingered. Here in the store I was finding This Island Earth, The Conquest of Space, Earth vs. The Flying Saucers, Forbidden Planet, Rocketship X-M and The Day the Earth Stood Still. Not to mention Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

Note that I’ve linked to some of these but not others. Read on.

Image: Dr. Carrington and his fellow scientists of Polar Expedition 6 studying how the Thing reproduces in the greenhouse of an Arctic research station in 1951’s The Thing from Another World.

Naturally, I loaded up on the SF classics even as my son turned his nose up at this ancient material, with its wonky special effects and wooden dialogue. I never did make him a fan of older movies (not even after introducing him to the Quatermass films!), but just after I began publishing Centauri Dreams, I ran into an SF movie fan who far eclipsed my own knowledge of the genre. Larry Klaes was about the first person who started sending me regular comments on the articles here. That was just after I turned the comments section on in 2005. In the years since he has become a friend, an editorial confidant and a regular contributor.

Klaes on Film

Larry has been an author for most of his life, and he has demonstrated that for the past two decades with his extensive work for Centauri Dreams. His essays have ranged through astronomy, space science, and the history of humanity’s exploration of the heavens. Equally to our purposes, Larry has also had a life-lomg fascination with science fiction, which helped to spur his interest in space and related subjects from an early age.

You’ll notice that a number of the movies I mentioned above are linked to Larry’s articles on them. The ones without links are obvious targets for future essays. A look through the archives will demonstrate that Larry has tackled everything from 1951’s classic The Thing from Another World to Star Trek: The Motion Picture. He’s written in-depth analyses (and I do mean in-depth) on more recent titles like Interstellar and 2010: The Year We Make Contact. I disagreed with him completely on Interstellar, and disagreements are what make film criticism so much fun.

Moreover, Larry is the kind of film enthusiast who isn’t content simply to put forth his opinions. He digs into the research in such a way that he invariably finds things I had never heard of. He finds clips that illustrate his points and original screenplays that clarify directorial intent. He finds connections that most of us miss (see his treatment of 1955’s Conquest of Space in relation to the Swedish film Aniara and the genre he labels ‘Angst SF’). His coverage of Avatar was so comprehensive that I began talking to him about turning his essays into a book, a project that I look forward to participating in.

Larry’s latest is a deep dive into Aniara, little known in the US, with its depiction of off-world migration and a voyage gone terribly wrong. The film possesses a thematic richness that Larry fully explores as the passengers and crew adapt to dire circumstances with the help of immersive virtual reality. When I read this, I decided it was time to give Larry space in a separate section, as the blog format is too constricted for long-form work. Have a look at the top of the home page and you’ll now see the tab Klaes on Film. The Aniara piece is there, inset into a redesigned workspace that offers ready navigation through the text.

Image: I loved the film but Larry’s look at Interstellar makes incsize points about film-making, public perception and the development of the interstellar idea.

All of Larry’s film essays are now available in the new section, but thus far only the current one on Aniara is embedded in the new format. I’ll be seeing to it that all of the essays are reformatted going forward, so that the disadvantages of the blog format for longer writing are eased.

The goal is to create a space for film criticism that acknowledges the hold the SF genre has acquired over the general public, in many cases inspiring career choices and adjusting how the average person views the interstellar challenge. This is a long-term project, but my web developer Ryan Given at StudioRTP is brilliant at customizing the site’s code and he knows where we’re going from here. I couldn’t keep this site going without Ryan’s expert guidance.

As my own passions in film are by today’s standards archaic (I’m still a black and white guy at heart), I’m glad to have someone who can tackle not just the classics of the field but also the latest blockbusters and the quirky outliers. And I wouldn’t mind seeing Larry’s thoughts on the TV version of Asimov’s Foundation either. Let’s keep him busy.

New Uses for the Eschaton 17 Dec 2025 5:29 AM (25 days ago)

One way to examine problems with huge unknowns – SETI is a classic example – is through the construction of a so-called ‘toy model.’ I linger a moment on the term because I want to purge the notion that it infers a lightweight conclusion. A toy model simplifies details to look for the big picture. It can be a useful analytical tool, a way of screening out some of the complexities in order to focus on core issues. And yes, it’s theoretical and idealized, not predictive.

But sometimes a toy model offers approaches we might otherwise miss. Consider how many variables we have to work with in SETI. What kind of signaling strategy would an extraterrestrial civilization choose? What sort of timeframe would it operate under? What cultural values determine its behavior? What is its intent? You can see how long this list can become. I’ll stop here.

The toy model I want to focus on today is one David Kipping uses in a new paper called “The Eschatian Hypothesis.” The term refers to what we might call ‘final things.’ Eschaton is a word that turns up in both cosmology and theology, in the former case talking about issues like the ultimate fate of the cosmos. So when Kipping (Columbia University) uses it in a SETI context, he’s going for the broadest possible approach, the ‘big picture’ of what a detection would look like.

I have to pause here for a moment to quote science fiction writer Charles Stross, who finds uses for ‘eschaton’ in his Singularity Sky (Ace, 2004), to wit:

I am the Eschaton. I am not your God.

I am descended from you, and exist in your future.

Thou shalt not violate causality within my historic light cone. Or else.

Love the ‘or else.’

Let’s now dig into the new paper. Published in Research Notes of the AAS, the paper homes in on a kind of bias that haunts our observations. Consider that the first exoplanets ever found were at the pulsar PSR 1257+12. Or the fact that the first main sequence star with a planet was found to host a ‘hot Jupiter,’ which back in 1995, when 51 Pegasi b was discovered, wasn’t even a category anyone ever thought existed. The point is that we see the atypical first precisely because such worlds are so extreme. While our early population of detections is packed with hot Jupiters, we have learned that these worlds are in fact rarities. We begin to get a feel for the distribution of discoveries.

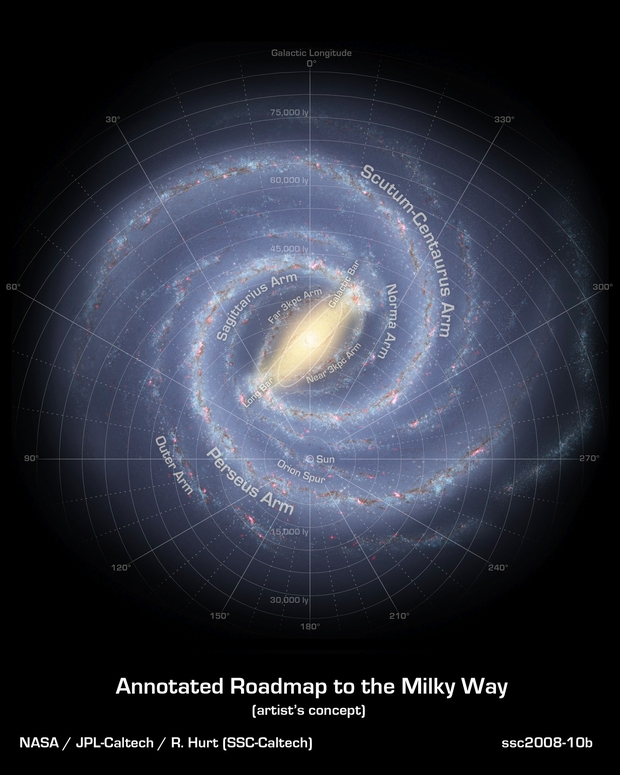

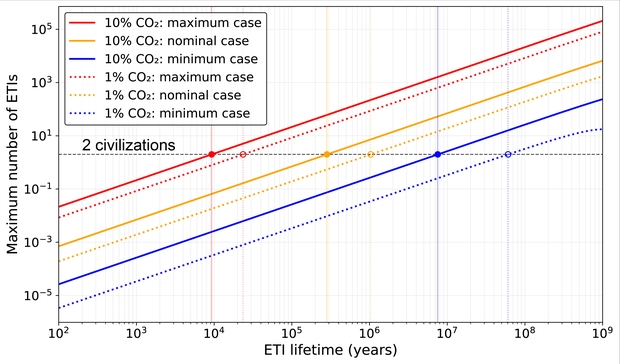

Hot Jupiters, in other words, are ‘loud.’ They’re the easiest of all radial velocity planet signatures to find. And yet they make up less than one percent of the exoplanets we’ve thus far found. The issue is broad. From the paper:

…over-representation of unusual astronomical phenomena in our surveys is not limited to exoplanetary science. One merely needs to look up at the night sky to note that approximately a third of the naked-eye stars are evolved giants, despite the fact less than one percent of stars are in such a state—a classic observational effect known as Malmquist bias (K. G. Malmquist 1922). Or consider that a supernova is expected roughly twice per century in Milky Way-sized galaxies (G. A. Tammann et al. 1994)—an astoundingly rare event. And yet, despite being an inherently rare type of transient, astronomers routinely detect thousands of supernovae every year (M. Nicholl 2021), as a product of their enormous luminosities.

That’s quite a thought. Go for a walk on a clear winter evening and look up. So many of the stars you’re seeing are giants in the terminal stages of their lifetimes. Those we can see at great range, but our nearest star, Proxima Centauri, demands a serious telescope for us to be able to see it. So we can’t help the bias that sets in until we realize how much of what we are seeing is rare. Sometimes we have to step back and ask ourselves why we are seeing it.

In SETI terms, Kipping steps back from the question to ask whether the first signatures of ETI, assuming one day they appear, will not be equally ‘loud,’ in the same way that supernovae are loud but actually quite rare. We might imagine a galaxy populated by stable, quiescent populations that we are not likely to see, cultures whose signatures are perhaps already in our data and accepted as natural. These are not the civilizations we would expect to see. What we might detect are the outliers, unstable cultures breaking into violent disequilibrium at the end of their lifetimes. These, supernova style, would be the ones that light up our sky.

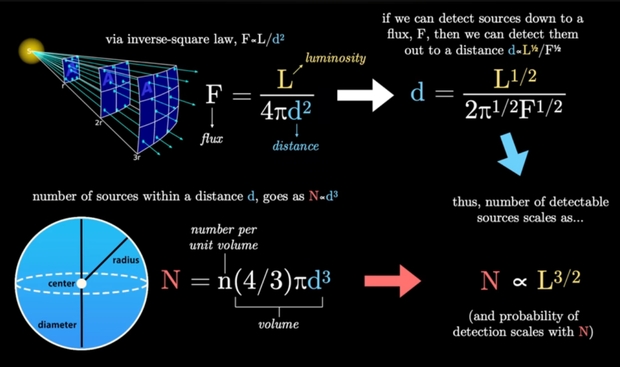

Kipping’s toy model works on variables of average lifetime and luminosity, examining the consequences on detectability. A loud civilization is one that becomes highly visible for a fraction of its lifetime before going quiet for the rest. The model’s math demonstrates that a civilization that is 100 times louder than its peers – through any kind of disequilibrium with its normal state, as for example nuclear war or drastic climate change – becomes 1000 times more detectable. A supernova is incredibly rare, but also incredibly detectable.

Image: The toy model at work. This is from Kipping’s Cool Worlds video on the Eschatian Hypothesis.

The Eschatian search strategy involves wide-field, high cadence surveys. In other words, observe at short intervals and keep observing with rapid revisit times to the same source. A search like this is optimized for transients, and the author points out that a number of observatories and observing programs are “moving toward a regime where the sky is effectively monitored as a time-domain data set.” The Vera Rubin Observatory moves in this direction, as does PANOPTES (Panoptic Astronomical Networked Observatories for a Public Transiting Exoplanet Survey). The latter is not a SETI program, but its emphasis on short-duration, repeatable events falls under the Eschatian umbrella.

Rather than targeting narrowly defined technosignatures, Eschatian search strategies would instead prioritize broad, anomalous transients—in flux, spectrum, or apparent motion—whose luminosities and timescales are difficult to reconcile with known astrophysical phenomena. Thus, agnostic anomaly detection efforts (e.g., D. Giles & L. Walkowicz 2019; A. Wheeler & D. Kipping 2019) would offer a suggested pathway forward.

I’ve often imagined the first SETI detection as marking a funeral beacon, though likely not an intentional one. The Eschatian Hypothesis fits that thought nicely, but it also leaves open the prospect of what we may not detect until we actually go into the galaxy, the existence of civilizations whose lifetimes are reckoned in millions of years if not more. The astronomer Charles Lineweaver has pointed out that most of our galaxy’s terrestrial-class worlds are two billion years older than Earth. Kipping quotes the brilliant science fiction writer Karl Schroeder when he tunes up an old Arthur Clarke notion: Any sufficiently advanced civilization will be indistinguishable from nature. Stability infers coming to terms with societal disintegration and mastering it.

Cultures like that are going to be hard to distinguish from background noise. We’re much more likely to see a hard-charging, shorter-lived civilization meeting its fate.

The paper is Kipping, “The Eschatian Hypothesis,” Research Notes of the AAS Vol. 9, No. 12 (December, 2025), 334. Full text.

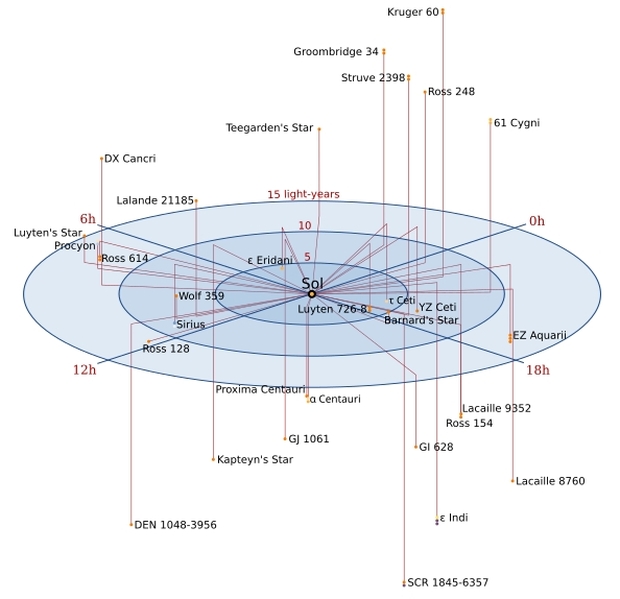

A ‘Tatooine’ Planet Directly Imaged 11 Dec 2025 10:34 AM (last month)

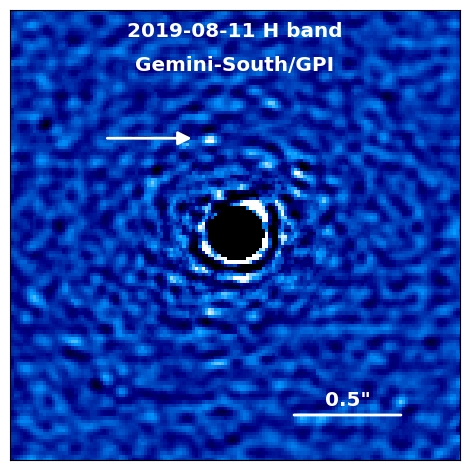

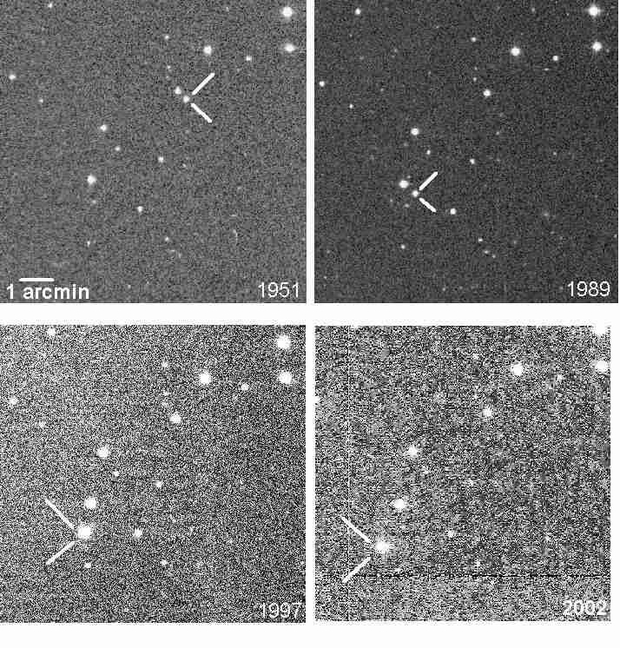

I jump at the chance to see actual images – as opposed to light curves – of exoplanets. Thus recent news of a Tatooine-style planetary orbit around twin stars, and what is as far as I know the first actually imaged planet in this orbital configuration. I’m reminded not for the first time of the virtues of the Gemini Planet Imager, so deft at masking starlight to catch a few photons from a young planet. Youth is always a virtue when it comes to this kind of thing, because young planets are still hot and hence more visible in the infrared.

The Gemini instrument is a multitasker, using adaptive optics as well as a coronagraph to work this magic. The new image comes out of an interesting exercise, which is to revisit older GPI data (2016-2019) at a time when the instrument is being upgraded and in the process of being moved to Hawaii from Chile, for installation on the Gemini North telescope on Mauna Kea. This reconsideration picked out something that had been missed. Cross-referencing data from the Keck Observatory, what was clearly a planet now emerged.

Image: By revisiting archival data, astronomers have discovered an exoplanet bound to binary stars, hugging them six times closer than other directly imaged planets orbiting binary systems. Above, the Gemini South telescope in Chile, where the data were collected with the help of the Gemini Planet Imager. Photo credit International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/T. Matsopoulos.

European astronomers at the University of Exeter independently report their own discovery of this planet in a paper in Astronomy & Astrophysics using GPI data in conjunction with ESO’s SPHERE instrument. So this appears to be a dual discovery and the planet is now obviously confirmed. More about the Exeter work in a moment.

Jason Wang is senior author of the Northwestern University study, which appears in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. There are obvious reasons why he and his collaborators are excited about this particular catch:

“Of the 6,000 exoplanets that we know of, only a very small fraction of them orbit binaries. Of those, we only have a direct image of a handful of them, meaning we can have an image of the binary and the planet itself. Imaging both the planet and the binary is interesting because it’s the only type of planetary system where we can trace both the orbit of the binary star and the planet in the sky at the same time. We’re excited to keep watching it in the future as they move, so we can see how the three bodies move across the sky.”

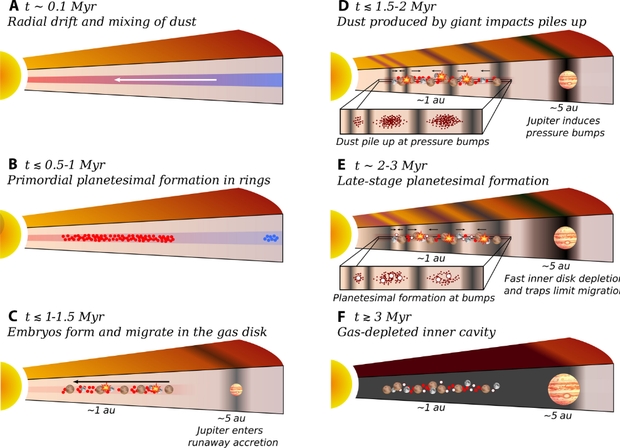

So what do we know about HD143811 AB b? No other directly imaged planet in a binary system presents us with such a tight orbit around its stars. This world is fully six times closer to its primaries than any other planets in a similar orbit, which says a good deal about GPI’s capabilities. The planet itself is mammoth, six times the size of Jupiter, and evidently relatively cool compared to other directly imaged planets. Formation is thought to have taken place about 13 million years ago, so we’re dealing with a very youthful star but not an infant.

The stars are part of the Scorpius-Centaurus OB association of young stars. The HD 143811 system itself is some 446 light years away. And what a tight binary this appears to be, the twin stars taking a mere 18 Earth days to complete one orbit around their common barycenter. Their giant offspring (assuming this world formed from their circumstellar disk), orbits the twin stars in 300 years.

I suspect that the orbital period is going to get revised. As Wang says: “You have this really tight binary, where stars are dancing around each other really fast. Then there is this really slow planet, orbiting around them from far away. Exactly how it works is still uncertain. Because we have only detected a few dozen planets like this, we don’t have enough data yet to put the picture together.”

The European work, likewise consulting older GPI data, shows an orbital period with wide error margins, a “mostly face-on and low-eccentricity orbit” with a very loosely constrained period of roughly 320 years.” The COBREX (COupling data and techniques for BReakthroughs in EXoplanetary systems exploration) project specializes in re-examining data like that of the GPI, working with high-contrast imaging, spectroscopy, and radial velocity measurements. In this case, the work included a new observation from the SPHERE (Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch) instrument installed at ESO’s Very Large Telescope in Chile.

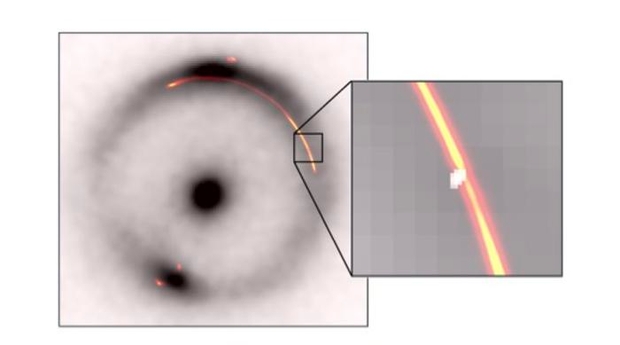

Image: HD 143811 AB b, now confirmed by two independent teams of astronomers, using direct imaging data from both the Gemini Planet Imager and the Keck Observatory. The Exeter team confirmed the discovery using ESO’s SPHERE instrument. Credit: Squicciarini et. al.

I mentioned the issue of the new planet’s formation. That’s one of the reasons this discovery is going to make waves. The overview from Exeter:

This discovery adds an important data point for comparative exoplanetology, bridging the temperature range between AF Lep b (De Rosa et al. 2023; Mesa et al. 2023; Franson et al. 2023) and cooler planets with a slightly lower mass, such as 51 Eri b (Macintosh et al. 2015). Together, these directly imaged planets of varying ages and masses offer a unique testbed for models of giant planet cooling and evolution. Moreover, HD 143811 b joins the small sample of circumbinary planets detected in imaging. Monitoring the binary with radial velocities and interferometry, along with astrometric orbit follow-up, will constrain the dynamical history of the system. While a characterization of the atmosphere is currently limited by the spectral coverage, broader wavelength and high-resolution observations especially in the mid-infrared will be essential for probing temperature structure and composition. This characterization will clarify the differences between circumbinary and single-star planets and their relation to free-floating objects.

The discovery was announced in two papers. The Northwestern offering is Jones et al. “HD 143811 AB b: A directly imaged planet orbiting a spectroscopic binary in Sco-Cen,” (11 December 2025). Now available as a preprint, with publication in process at The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The University of Exeter discovery paper is Squicciarini et al., “GPI+SPHERE detection of a 6.1 MJup circumbinary planet around HD 143811,” Astronomy & Astrophysics Vol. 702 (2025), L10 (full text).

Catching Up with TRAPPIST-1 9 Dec 2025 9:51 AM (last month)

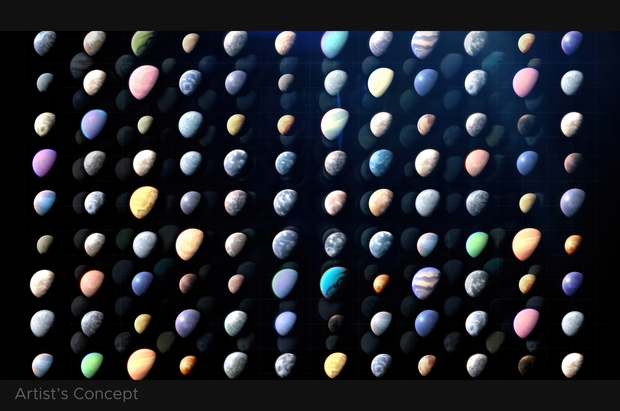

Let’s have a look at recent work on TRAPPIST-1. The system, tiny but rich in planets (seven transits!) continues to draw new work, and it’s easy to see why. Found in Aquarius some 40 light years from Earth, a star not much larger than Jupiter is close enough for the James Webb Space Telescope to probe the system for planetary atmospheres. Or so an international team working on the problem believes, with interesting but frustratingly inconclusive results.

As we’ll see, though, that’s the nature of this work, and in general of investigations of terrestrial-class planet atmospheres. I begin with news of TRAPPIST-1’s flare activity. One of the reasons to question the likelihood of life around small red stars is that they are prone to violent flares, particularly in their youth. Planets in the habitable zone, and there are three here, would be bathed in radiation early on, conceivably stripping their atmospheres entirely, and certainly raising doubts about potential life on the surface.

Image: Artist’s concept of the planet TRAPPIST-1d passing in front of the star TRAPPIST-1. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Joseph Olmsted/STScI.

A just released paper digs into the question by applying JWST data on six flares recorded in 2022 and 2023 to a computer model created by Adam Kowalski (University of Colorado Boulder), who is a co-author on the work. The equations of Kowalski’s model allow the researchers to probe the stellar activity that created the flares, which the authors see as deriving from magnetic reconnection that heats stellar plasma through pulses of electron beaming.

The scientists are essentially reverse-engineering flare activity with an eye to understanding how it might affect an atmosphere, if one exists, on these planets. The extent of the activity came as something of a surprise. As lead author Ward Howard (also at University of Colorado Boulder) puts it: “When scientists had just started observing TRAPPIST-1, we hadn’t anticipated the majority of our transits would be obstructed by these large flares.”

Which would seem to be bad news for biology here, but we also learn from Kowalski’s equations that TRAPPIST-1 flares are considerably weaker than supposed. We can couple this result with two papers published earlier this year in the Astrophysical Journal Letters. Using transmission spectroscopy and working with JWST’s Near-Infrared Spectrograph and Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph, the researchers looked at TRAPPIST-1e as it passed in front of the host star. A third paper, released on December 5, examines these data and the possibility of methane in an atmosphere. Here we run into the obvious limitations of modeling.

The most recent paper is out of the University of Arizona, where Sukrit Ranjan and team have gone to work on methane in an M-dwarf planet atmosphere. With an eye toward TRAPPIST-1e, they note this (italics mine):

We have shown that models that include CH4 are viable fits to TRAPPIST-1e’s transmission spectrum through both our forward-model analysis and retrievals. However, we stress that the statistical evidence falls far below that required for a detection. While an atmosphere containing CH4 and a (relatively) spectrally quiet background gas (e.g., N2) provides a good fit to the data, these initial TRAPPIST-1 e transmission spectra remain consistent with a bare rock or cloudy atmosphere interpretations. Additionally, we note that our “best-fit” CH4 model does not explain all of the correlated features present in the data. Here we briefly examine the theoretical plausibility of a N2–CH4 atmosphere on TRAPPIST-1 e to contextualize our findings.

Should we be excited by even a faint hint of an atmosphere here? Probably not. The paper simulates methane-rich atmosphere scenarios, but also discusses alternative possibilities. Here we get a sense for how preliminary all our TRAPPIST-1 work really is (and remember that JWST is working at the outer edge of its limits in retrieving the data used here). A key point is that TRAPPIST-1 is significantly cooler than our G-class Sun. As Ranjan points out:

“While the sun is a bright, yellow dwarf star, TRAPPIST-1 is an ultracool red dwarf, meaning it is significantly smaller, cooler and dimmer than our sun. Cool enough, in fact, to allow for gas molecules in its atmosphere. We reported hints of methane, but the question is, ‘is the methane attributable to molecules in the atmosphere of the planet or in the host star?…[B]ased on our most recent work, we suggest that the previously reported tentative hint of an atmosphere is more likely to be ‘noise’ from the host star.”

The paper notes that any spectral feature from an exoplanet could have not just stellar origins but also instrumental causes. In any case, stellar contamination is an acute problem because it has not been fully integrated into existing models. The approach is Bayesian, given that the plausibility of any specific scenario for an atmosphere has an effect on the confidence with which it can be identified in an individual spectrum. Right now we are left with modeling and questions.

Ranjan believes that the way forward for this particular system is to use a ‘dual transit’ method, in which the star is observed when both TRAPPIST-1e and TRAPPIST-1b move in front of the star at the same time. The idea is to separate stellar activity from what may be happening in a planetary atmosphere. As always, we look to future instrumentation, in this case ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope, which is expected to become available by the end of this decade. And next year NASA will launch the Pandora mission, a small telescope but explicitly designed for characterizing exoplanet atmospheres.

More questions than answers? Of course. We’re pushing hard against the limits of detection, but all these models help us learn what to look for next. Nearby M-dwarf transiting planets, with their deep transit depths, higher transit probability in the habitable zone and frequent transit opportunities, are going to be commanding our attention for some time to come. As always, patience remains a virtue.

Here’s a list of the papers I’ve discussed here. The flare modeling paper is Howard et al., “Separating Flare and Secondary Atmospheric Signals with RADYN Modeling of Near-infrared JWST Transmission Spectroscopy Observations of TRAPPIST-1,” Astrophysical Journal Letters Vol. 994, No. 1 (20 November 2025) L31 (full text).

The paper on methane detection and stellar activity is Ranjan et al., “The Photochemical Plausibility of Warm Exo-Titans Orbiting M Dwarf Stars,” Astrophysical Journal Letters Vol. 993, No. 2 (3 November 2025), L39 (full text).

The earlier papers of interest are Glidden et al., “JWST-TST DREAMS: Secondary Atmosphere Constraints for the Habitable Zone Planet TRAPPIST-1 e,” Astrophysical Journal Letters Vol. 990, No. 2 (8 September 2025) L53 (full text); and Espinoza et al. “JWST-TST DREAMS: NIRSpec/PRISM Transmission Spectroscopy of the Habitable Zone Planet TRAPPIST-1 e,” Astrophysical Journal Letters Vol. 990, No. 2 (L52) (full text).

The Rest is Silence: Empirically Equivalent Hypotheses about the Universe 1 Dec 2025 10:52 AM (last month)

Because we so often talk about finding an Earth 2.0, I’m reminded that the discipline of astrobiology all too easily falls prey to an earthly assumption: Intelligent beings elsewhere must take forms compatible with our planet. Thus the recent post on SETI and fireflies, one I enjoyed writing because it explores how communications work amongst non-human species here on Earth. Learning about such methods may lessen whatever anthropomorphic bias SETI retains. But these thoughts also emphasize that we continue to search in the dark. It’s a natural question to ask just where SETI goes from here. What happens if in all our work, we continue to confront silence? I’ve been asked before what a null result in SETI means – how long do we have to keep doing this before we simply acknowledge that there is no one out there? But a better question is, how would we ever discover a definitive answer given the scale of the cosmos? If not in this galaxy, maybe in Andromeda? If not there, M87?

In today’s essay, Nick Nielsen returns to dig into how these questions relate to the way we do science, and ponders what we can learn by continuing to push out into a universe that remains stubbornly unyielding in its secrets. Nick is an independent scholar in Portland OR whose work has long graced these pages. Of late he has been producing videos on the philosophy of history. His most recent paper is “Human Presence in Extreme Environments as a Condition of Knowledge: An Epistemological Inquiry.” As Breakthrough Listen continues and we enter the era of the Extremely Large Telescopes, questions like these will continue to resonate.

by J. N. Nielsen

What would it mean for humanity to be truly alone in the universe? In an earlier Centauri Dreams post, SETI’s Charismatic Megafauna, I discussed the tendency to focus on the extraterrestrial equivalent of what ecologists sometimes call “charismatic megafauna”—which in the case of SETI consists of little green men, space aliens, bug-eyed monsters, Martians, and their kin—whereas life and intelligence might take very different forms from those with which we’re familiar. [1] We might not feel much of a connection to the discovery of an exoplanet covered in a microbial mats, which couldn’t respond to us, much less communicate with us, but it would be evidence that there is other life in the universe, which suggests there may be other life yet to be found, which also would mean that, as life, we aren’t utterly alone in the universe. This in turn suggests the alternative view that we might be utterly alone, without a trace of life beyond Earth, and this gets to some fundamental questions. One way to cast some light on these questions is through a thought experiment that would bring the method of isolation to bear on the problem. I will focus on a single, narrow, unlikely scenario as a way to think about what it would mean to be truly alone in the universe.

Suppose, then, we find ourselves utterly alone in the universe—not only alone in the sense of there being no other intelligent species with whom we could communicate, and no evidence of any having existed in the universe’s past (from which we could experience unidirectional communication), but utterly alone in the sense that there’s not any sign of life in the universe, not even microbes. This scenario begins where we are today, inhabiting Earth, looking out into the cosmos to see what we can see, listening for SETI transmissions, trying to detect life elsewhere, and planning missions and designing spacecraft to extend this search further outward into the universe. This thought experiment, then, is consistent with what we know of the universe today; it is empirically equivalent to a universe positively brimming with other life and other civilizations that we just haven’t yet found; at our current level of technology and cosmological standing, we can’t distinguish between the two scenarios.

There is a cluster of related problems in the philosophy of science, including the underdetermination of theories, the possibility of empirically equivalent theories, theory choice, and holism in confirmation. I’m going to focus on the possibility of empirically equivalent theories, but what follows could be reformulated in terms of the others. What is it for a theory to be underdetermined? “To say that an outcome is underdetermined is to say that some information about initial conditions and rules or principles does not guarantee a unique solution.” (Lipton 1991: 6) If there’s no unique solution, there may be many possible solutions. Empirically equivalent theories are these many possible solutions. [2]

The discussion of empirically equivalent theories today has focused on the expansion of the consequence class of a theory, i.e., adopting auxiliary hypotheses so as to derive further testable consequences. We’re going to look at this through the other end of the telescope, however. Two theories can have radically different consequence classes while our ability conduct observations that would confirm or disconfirm these consequence classes is so limited that the available empirical evidence cannot distinguish between the two theories. That our ability to observe changes, and therefore the scope of the empirical consequence class changes, due to technologies and techniques of observation has been called “variability of the range of observation” (VRO) and the “inconstancy of the boundary of the observable.” (discussed in Laudan and Leplin 1991). Given VRO, there may be a time in the history of science when the observable consequence classes of two theories coincide, even while their unobservable consequence class ultimately diverges; at this time, the two theories are empirically equivalent in the sense that no current observation can confirm one while disconfirming the other. This is why we build larger telescopes and more powerful particle accelerators: to gain access to observations that can decide between theories that are empirically equivalent at present, but which have divergent consequence classes.

Returning to our thought experiment, where we began as we are today (unable to distinguish between a populous universe and terrestrial exceptionalism)—what do we do next? In our naïveté we make progress with our ongoing search. We build better telescopes, and we orbit larger and more sophisticated telescopes, with the intention of performing exoplanet atmospheric spectroscopy. We build spacecraft that allow us to explore our solar system. We go to Mars, but we don’t find anything there; no microbes in the permafrost or deep in subterranean bodies of water, and no sign of any life in the past. But we aren’t discouraged by this, because it’s always been possible that there was never life on Mars. There are many other places to explore in our solar system. Eventually we travel to interesting places like Titan, with its own thick atmosphere. We find this moon to be scientifically fascinating, but, again, no life of any kind is found. We send probes into subsurface liquid water oceans, first on Enceladus, then Europa, and we find nothing more complex in these waters than what we see in the astrochemistry of deep space: some simple organic molecules, but no macromolecules. Again, these worlds are scientifically fascinating, but we don’t find life and, again, we aren’t greatly bothered because we’ve only recently accustomed ourselves to the idea that there might be life in these oceans, and we can readily un-accustom ourselves as quickly. But it does raise questions, and so we seek out all the subsurface oceans in our solar system, even the brine pockets under the surface of Ceres, this time with a little more urgency. Again, we find many things of scientific interest, but no life, and no other unexpected forms of emergent complexity.

Suppose we exhaust every potential niche in our solar system, from the ice deep in craters on Mercury, to moons and comets in the outer solar system, and we find no life at all, and nothing like life either—no weird life (Toomey 2013), no life-as-we-do-not-know-it (Ward 2007), and no alternative forms of emergent complexity that are peers of life (Nielsen 2024). All the while as we’ve been exploring our solar system, our cosmological “backyard” as it were, we’ve continued to listen for SETI signals, and we’ve heard nothing. And we’ve continued to pursue exoplanet atmospheric spectroscopy, and we have a few false positives and a few mysteries—as always, scientifically interesting—but no life and no intelligence betrays itself. Now we’re several hundred years in the future, with better technology, better scientific understanding, and presumably a better chance of finding life, but still nothing.

If we had had some kind of a hint of possible life on another world, we could have had some definite target for the next stage of our exploration, but so far we’ve drawn a blank. We could choose our first interstellar objective by flipping a coin, but instead we choose to investigate the strangest planetary system we can find, with some mysterious and ambiguous observations that might be signs of biotic processes we don’t understand. And so we begin our interstellar exploration. Despite choosing a planetary system with ambiguous observations that might betray something more complex going on, once we arrive at the other planetary system and investigate it, we once again come up empty-handed. The investigation is scientifically interesting, as always, but it yields no life. Suppose we investigate this other planetary system as thoroughly as we’ve investigated our own solar system, and the whole thing, with all its potential niches for life, yields nothing but sterile, abiological processes, and nothing that on close inspection can’t be explained by chemistry, mineralogy, and geology.

Again we’re hundreds of years into the future, with interstellar exploration under our belt, and we still find ourselves alone in the cosmos. Not only are we alone in the cosmos, but the rest of the cosmos so far as we have studied it, is sterile. Nothing moves except that life that we brought with us from Earth. Still hundreds of years into the future and with all this additional exploration, and the scenario remains consistent with the scenario we know today: no life known beyond Earth. We can continue this process, exploring other scientifically interesting planetary systems, and trying our best to exhaustively explore our galaxy, but still finding nothing. At what threshold does this unlikelihood rise to the level of paradoxicality? Certainly at this point the strangeness of the situation in which we found ourselves would seem to require an explanation. So instead of merely searching for life, wherever we go we also seek to confirm that the laws of nature we’ve formulated to date remain consistent. That is to say, we test science for symmetry, because if we are able to find asymmetry, we will have found a limit to scientific knowledge.

We don’t have any non-arbitrary way to limit the scope of our scientific findings. If any given scientific findings could be shown to fail under translation in space or translation in time, then we would have reason to restrict their scope. Indeed, if we were to discover that our scientific findings fail beyond a given range in space and time, there would be an intense interest in exploring that boundary, mapping it, and understanding it. Eventually, we would want to explain this boundary. But without having discovered this boundary, we find ourselves in a quandary. Our science ought to apply to the universe entire. At least, this is the idealization of scientific knowledge that informs our practice. “On the one hand, there are truths founded on experiment, and verified approximately as far as almost isolated systems are concerned; on the other hand, there are postulates applicable to the whole of the universe and regarded as rigorously true.” (Poincaré 1952: 135-136) Earth and its biosphere are effectively an isolated system in Poincaré’s sense. We’ve constructed a science of biology based on experimentation within that isolated system (“verified approximately as far as almost isolated systems are concerned”), and the truths we’ve derived we project onto the universe (“applicable to the whole of the universe”). But our extrapolation of what we observe locally is an idealization, and our projecting a postulate onto the universe entire is equally an idealization. We can no more realize these idealizations in fact than we can construct a simple pendulum in fact. [3]

We need to distinguish between, on the one hand, that idealization used in science and without which science is impossible (e.g., the simple pendulum mentioned above), and, on the other hand, that idealization that is impossible for science to capture in any finite formalization, but which can be approximated (like the ideal isolation of experiment discussed by Poincaré). Holism in confirmation, to which I referred above (and which is especially associated with Duhem-Quine thesis), is an instance of this latter kind of idealization. Both forms of idealization force compromises upon science through approximation; we accept a result that is “good enough,” even if not perfect. Each form of idealization implies the other, as, for example, the impossibility of accounting for all factors in an experiment (idealized isolation) implies the use of a simplified (ideal) model employed in place of actual complexity. Thus one ideal, realizable in theory, is substituted for another ideal, unrealizable in theory.

Our science of life in the universe, i.e., astrobiology, involves these two forms of idealization. Our schematic view of life, embodied in contemporary biology (for example, the taxonomic hierarchy of kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species, or the idealized individuation of species), is the idealization realizable in theory, while the actual complexity of life, the countless interactions of actual biological individuals within a population both of others of its own species and individuals of other species, not to mention the complexity of the environment, is the idealization unrealizable in theory. The compromises we have accepted up to now, which have been good enough for the description of life on Earth, may not be adequate in an astrobiological context. Thus the testing of science for symmetries in space and time ought to include the testing of biology for symmetries, but, since in this thought experiment there are no other instances of biology beyond Earth, we cannot test for symmetry in biology as we would like to.

Suppose that our research confirms that as much of our science as can be tested is tested, and this science is as correct as it can be, and so it should be predictive, even if it doesn’t seem to be doing a good job at predicting what we find on other worlds. We don’t have to stop there, however. If we don’t find other living worlds in the cosmos, we might be able to create them. Exploring the universe on a cosmological scale would involve cosmological scales of time. If we were to travel to the Andromeda galaxy and back, about four million years would elapse back in the Milky Way. If we were to travel to other galaxy clusters, tens of millions of years or hundreds of millions of years would elapse. These are biologically significant periods of time, by which I mean these are scales of time over which macroevolutionary processes could take place. Our cosmological exploration would give us an opportunity to test that. In the sterile universe that we’ve discovered in this thought experiment, we still have the life from Earth that we’ve brought to the universe, and over biological scales of time life from Earth could go on to its own cosmological destiny. In our exploration of a sterile universe, we could plant the seeds of life from Earth and seek to create the biological universe we expected to find. The adaptive radiation of Earth life, facilitated by technology, could supply to other worlds the origins of life, and if origins of life were the bottleneck that produced a sterile universe, then once we supply that life to other worlds, these other worlds should develop biospheres in a predictable way (within expected parameters).

It probably wouldn’t be as easy as leaving some microbes on another planet or moon; we would have to prepare the ground for them so they weren’t immediately killed by the sterile environment. In other words, we would have to practice terraforming, at least to the extent of facilitating the survival, growth, and evolution of rudimentary Earth life on other worlds. If every attempt at terraforming immediately failed, that would be as strange as finding the universe to be sterile, and perhaps more inexplicable. But that’s a rather artificial scenario. It’s much more realistic to imagine that we attempt the terraforming of many worlds, and, despite some initial hopeful signs, all of our attempts at terraforming eventually die off, all for apparently different reasons, but none of them “take.” This would be strange, but we could still seek some kind of scientific explanation for this that demonstrated truly unique forces to be at work on Earth that allowed the biosphere not only to originate but to survive over cosmological scales of time (the “rare Earth” hypothesis with a vengeance).

If the seeding of Earth life on other worlds didn’t end in this strange way (as strange as the strangeness of exploring a sterile universe, so it’s a continued strangeness), but rather some of these terraforming experiments were successful, what comes next could entail a number of possible outcomes of ongoing strangeness. Leaving our galaxy for a few billion years of exploration in other galaxies, upon our return we could study these Earth life transplantations. Transplanted Earth life on other worlds could very nearly reproduce the biosphere on Earth, which would suggest very tight constraints of convergent evolution. If origins of life are very rare, and conditions for the further evolution of life are tightly constrained by convergent evolution, that would partially explain why we found a sterile universe, but the conditions would be far stronger than we would expect, and that would be scientifically unaccountable.

Another strange outcome would be if our terraformed worlds with transplanted Earth life all branched out in radically different directions over our multi-billion year absence exploring other galaxies. We would expect some branching out, but there would be a threshold of branching out, with none of the biospheric outcomes even vaguely resembling any of the others, that would defy expectations, and, in defying expectations, we would once again find ourselves faced with conditions much stronger than we would expect. In all these cases of strangeness—the strangeness of all our engineered biospheres failing, the strangeness of our engineered biospheres reproducing Earth’s biosphere to an unexpected degree of fidelity, and the strangeness of our engineered biospheres all branching off in radically different directions—we would confront something scientifically unaccountable. Even though we have no experience of other biospheres, we still have expectations for them based on the kind of norms we’ve come to expect from hundreds of years of practicing science, and departure from the norms of naturalism is strange. All of these scenarios would be strange in the sense of defying scientific expectations, and that would make them all scientifically interesting.

These scenarios are entirely consistent with our current observations, so that a sterile universe with Earth as the sole exception where life is to be found is, at the present time, empirically equivalent with a living universe in which life is commonplace. However, the exploration of our own solar system could offer further confirmation of a sterile universe, or disconfirm it, or modify it. If, as in the preceding scenario, we find nothing at all beyond Earth in our solar system, this will increase the degree of confirmation for the sterile universe hypothesis (which we could also call terrestrial exceptionalism). If we were to find life elsewhere in our solar system, but molecular phylogeny shows that all life in our solar system derives from a single origins of life event, then we will have demonstrated that life as we know it can be exchanged among worlds, but the likelihood of independent origins of life events would be rendered somewhat less probable, especially if we were to determine that any of the over life-bearing niches in our solar system were not only habitable, but unambiguously urable. [4]

If we were to find life elsewhere in our solar system and molecular phylogeny shows that these other instances of life derive from independent origins of life events, then this would increase the degree of confirmation of the predictability of origins of life events on the basis of our present understanding of biology. The number of distinct origins of life events could serve as a metric to quantify this. [5] If we were to find life elsewhere in the solar system and this life consists of an eclectic admixture of life with the same origins event as life on Earth, and life derived from distinct origins events, then we would know both that the distribution of life among worlds and origins of life were common, and on this basis we would expect to find the same in the cosmos at large. An exacting analysis of this maximal life scenario would probably yield interesting details, such as particular forms of life that appear the most readily once boundary conditions have been met, and particular forms of life that are more finicky and don’t as readily appear. Similarly, among life distributed across many worlds we would likely find that some varieties are more readily distributed than others.

If the solar system is brimming with life, we could still maintain that the rest of the cosmos is sterile, reproducing the same scenario as above, but the scenario would be less persuasive, or perhaps I should say less frightening, knowing that life had originated elsewhere and was not absolutely unique to Earth. Nevertheless, we could yet be faced with a scenario that is even more inexplicable than the above (call it the “augmented Fermi paradox” if you like). If we found our solar system to be brimming with life, with life easily originating and easily transferable among astronomical bodies, increasing our confidence that life is common in the universe and widely distributed, and then we went out to explore the wider universe and found it to be sterile, we would be faced with an even greater mystery than the mystery we face today. The dilemma imposed upon us by the Fermi paradox can yet take more severe forms than the form in which we know it today. The possibilities are all the more tantalizing given that at least some of these questions will be answered by evidence within our own solar system.

It seems likely that the Fermi paradox is an artifact of the contemporary state of science, and will persist as long as science and scientific knowledge retains its current state of conceptual development. Anglo-American philosophy of science has tended to focus on confirmation and disconfirmation of theories, while continental philosophy of science has developed the concept of idealization [6]; I have drawn on both of these traditions in the above thought experiment, and it will probably require resources from both of these traditions to resolve the impasse we find ourselves at present. Because science and scientific knowledge itself would be called into question in this scenario, there would be a need for human beings themselves to travel to the remotest parts of the universe to ensure the integrity of the scientific process and the data collected (Nielsen 2025b), and this will in turn demand heroic virtues (Nielsen 2025) on the part of those who undertake this scientific research program.

Thanks are due to Alex Tolley for suggesting this.

Notes

1. I have discussed different definitions of life in (Nielsen 2023), and I have formulated a common theoretical framework for discussing forms of life and intelligence not familiar to us in (Nielsen 2024b) and (Nielsen 2025a).

2. The discussion of empirically equivalent theories probably originates in (Van Fraassen 1980).

3. I am using “simple pendulum” here in the sense of an idealized mathematical model of a pendulum that assumes a frictionless fulcrum, a weightless string, a point mass weight bob, absence of air drag, short amplitude (small-angle approximation where sinθ≈θ), inelasticity of pendulum length, rigidity of the pendulum support, and a uniform field of gravity during operation of the pendulum. Actual pendulums can be made precise to an arbitrary degree, but they can never exhaustively converge on the properties of an ideal pendulum.

4. “Urable” planetary bodies are those that are, “conducive to the chemical reactions and molecular assembly processes required for the origin of life.” (Deamer, et al. 2022)

5. The degree of distribution of life from a single origins of life event, presumably a function of the particular form of life involved, the conditions of carriage (i.e., the mechanism of distribution), and the structure of the planetary system in question, would provide another metric relevant to assessing the ability of life to survive and reproduce on cosmological scales.

6. Brill has published fourteen volumes on idealization in the series Poznań Studies in the Philosophy of the Sciences and the Humanities.

References

Deamer, D., Cary, F., & Damer, B. (2022). Urability: A property of planetary bodies that can support an origin of life. Astrobiology, 22(7), 889-900.

Laudan, L. and Leplin, J. (1991). “Empirical Equivalence and Underdetermination.” Journal of Philosophy. 88: 449–472.

Lipton, Peter. (1991). Inference to the Best Explanation. Routledge.

Nielsen, J. N. (2023). “The Life and Death of Habitable Worlds.” Chapter in: Death And Anti-Death, Volume 21: One Year After James Lovelock (1919-2022). Edited by Charles Tandy. 2023. Ria University Press.

Nielsen, J. N. (2024a). Heroic virtues in space exploration: everydayness and supererogation on Earth and beyond,” Heroism Sci. doi:10.26736/hs.2024.01.12

Nielsen, J. N. (2024b). Peer Complexity in Big History. Journal of Big History, VIII(1); 83-98.

DOI | https://doi.org/10.22339/jbh.v8i1.8111 (An expanded version of this paper is to appear as “Humanity’s Place in the Universe: Peer Complexity, SETI, and the Fermi Paradox” in Complexity in Universal Evolution—A Big History Perspective.)

Nielsen, J.N. (2025a). An Approach to Constructing a Big History Complexity Ladder. In: LePoire, D.J., Grinin, L., Korotayev, A. (eds) Navigating Complexity in Big History. World-Systems Evolution and Global Futures. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-85410-1_12

Nielsen, J.N. (2025b). Human presence in extreme environments as a condition of knowledge: an Epistemological inquiry. Front. Virtual Real. 6:1653648. doi: 10.3389/frvir.2025.1653648

Poincaré, Henri. (1952). Science and Hypothesis. Dover.

Toomey, D. (2013). Weird life: The search for life that is very, very different from our own. WW Norton & Company.

Van Fraassen, B. C. (1980). The scientific image. Oxford University Press.

Ward, P. (2007). Life as we do not know it: the NASA search for (and synthesis of) alien life. Penguin.

The Firefly and the Pulsar 20 Nov 2025 6:27 AM (last month)

We’ve now had humans in space for 25 continuous years, a feat that made the news last week and one that must have caused a few toasts to be made aboard the International Space Station. This is a marker of sorts, and we’ll have to see how long it will continue, but the notion of a human presence in orbit will gradually seem to be as normal as a permanent presence in, say, Antarctica. But what a short time 25 years is when weighed against our larger ambitions, which now take in Mars and will continue to expand as our technologies evolve.

We’ve yet to claim even a century of space exploration, what with Gagarin’s flight occurring only 65 years ago, and all of this calls to mind how cautiously we should frame our assumptions about civilizations that may be far older than ourselves. We don’t know how such species would develop, but it’s chastening to realize that when SETI began, it was utterly natural to look for radio signals, given how fast they travel and how ubiquitous they were on Earth.

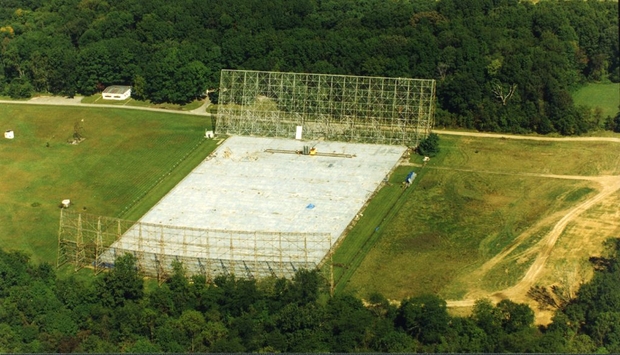

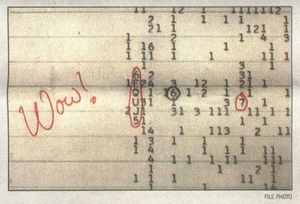

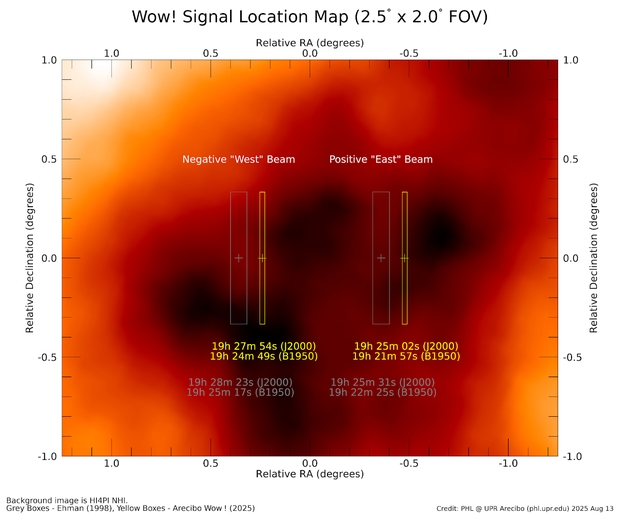

Today, though, things have changed significantly since Frank Drake’s pioneering work at Green Bank. We’re putting out a lot less energy in the radio frequency bands, as technology gradually shifted toward cable television and Internet connectivity. The discovery paradigm needs to grow lest we become anthropocentric in our searches, and the hunt for technosignatures reflects the realization that we may not know what to expect from alien technologies, but if we see one in action, we may at least be able to realize that it is artificial.

And if we receive a message, what then? We’ve spent a lot of time working on how information in a SETI signal could be decoded, and have coded messages of our own, as for example the famous Hercules message of 1974. Sent from Arecibo, the message targeted the Hercules cluster some 25,000 light years away, and was obviously intended as a demonstration of what might later develop with nearby stars if we ever tried to communicate with them.

But whether we’re looking at data from radio telescopes, optical surveys of entire galaxies or even old photographic plates, that question of anthropocentrism still holds. Digging into it in a provocative way is a new paper from Cameron Brooks and Sara Walker (Arizona State) and colleagues. In a world awash with papers on SETI and Fermi and our failure to detect traces of ETI, it’s a bit of fresh air. Here the question becomes one of recognition, and whether or not we would identify a signal as alien if we saw it, putting aside the question of deciphering it. Interested in structure and syntax in non-human communication, the authors start here on Earth with the common firefly.

If that seems an odd choice, consider that this is a non-human entity that uses its own methods to communicate with its fellow creatures. The well studied firefly is known to produce its characteristic flashes in ways that depend upon its specific species. This turns out to be useful in mating season when there are two imperatives: 1) to find a mate of the same species in an environment containing other firefly species, and 2) to minimize the possibility of being identified by a predator. All this is necessary because according to one recent source, there are over 2600 species in the world, with more still being discovered. The need is to communicate against a very noisy background.

Image: Can the study of non-human communication help us design new SETI strategies? In this image, taken in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, we see the flash pattern of Photinus carolinus, a sequence of five to eight distinct flashes, followed by an eight-second pause of darkness, before the cycle repeats. Initially, the flashing may appear random, but as more males join in, their rhythms align, creating a breathtaking display of pulsating light throughout the forest. Credit: National Park Service.

Fireflies use a form of signaling, one that is a recognized field of study within entomology, well analyzed and considered as a mode of communications between insects that enhances species reproduction as well as security. The evolution of these firefly flash sequences has been simulated over multiple generations. If fireflies can communicate against their local background using optical flashes, how would that communication be altered with an astrophysical background, and what can this tell us about structure and detectability?

Inspired by the example of the firefly, what Brooks and Walker are asking is whether we can identify structural properties within such signals without recourse to semantic content, mathematical symbols or other helpfully human triggers for comprehension. In the realm of optical SETI, for example, how much would an optical signal have to contrast with the background stars in its direction so that it becomes distinguishable as artificial?