AI Doesn’t Eliminate Agile Teams — It Increases the Need for Great Ones 2 Dec 6:00 AM (21 days ago)

Everyone today seems eager to talk about how AI is accelerating software development. Teams are shipping faster. Individuals are more productive. Entire backlogs can be written in minutes. Estimates are a click away. Code that once took days now materializes in minutes. With all this newfound speed, it’s understandable that teams and leaders start asking whether they still need the same kinds of collaboration—or even the same kinds of teams.

Yet hidden underneath all that enthusiasm is a risk that hasn’t received enough attention. In fact, I would argue it is the risk that agile leaders should be paying the closest attention to.

AI doesn’t eliminate teams; it increases the need for great ones.

The faster a team moves, the more collaboration it requires. The more productive individual contributors become, the more their work needs to be coordinated. And the more powerful AI becomes as a tool, the more dangerous it is when someone uses it in isolation. Put simply, AI amplifies everything—including misalignment.

Unfortunately, many teams are responding to AI by collaborating less. And that is where things begin to fall apart.

The Drift Away from Collaboration

Over the last few years, I’ve watched teams adopt AI tools in ways that unintentionally reduce communication. Developers can now accomplish huge amounts of work on their own. Product Owners can use AI to generate and split backlog items or even prioritize whole roadmaps. Teams start to believe they no longer need to talk as often because the tooling is doing so much of the work.

The theory goes: if AI can generate stories, code, and tests, perhaps the team can get by with fewer discussions.

The reality is very different.

I’ve seen teams that, excited by AI’s efficiency, quietly slip into working as a collection of individuals rather than as a cohesive unit. They may hold the same meetings, but the communication within those meetings becomes thin and surface-level. Outside the meetings, collaboration dwindles even further.

Example: A Team Moves Fast with AI, but Stops Talking

Consider one team that dramatically accelerated development because AI allowed it to refine and build features faster than ever. Impressed with the speed, they assumed their longstanding collaboration habits were no longer necessary. They talked less. They shared less. They coordinated less. And predictably, they began building a series of features that didn’t integrate well and didn’t match stakeholder expectations. They had increased their output but degraded their outcomes.

Their problem wasn’t AI.

Their problem was collaboration.

And AI simply magnified it.

How AI Is Transforming Roles—and Why That Matters

AI is not just speeding up development. It’s reshaping what the key roles inside agile teams actually do. These changes are significant, and understanding them helps us understand why collaboration remains so important.

Product Owners in the Age of AI: Supported, but at Risk of Over-Reliance

Product Owners may be the biggest beneficiaries of AI in the short term. AI can help them write backlog items, generate acceptance criteria, analyze customer sentiment, summarize research, and even propose priorities. For a role that has always struggled with having enough time to do the job, this is a welcome change.

But with that support comes temptation. It becomes too easy to delegate too much thinking to an AI. A Product Owner who lets AI drive backlog prioritization or roadmap decisions risks drifting away from customer needs, business realities, and strategic intent. AI can assist, but it cannot own core decisions such as product vision, market positioning, customer segmentation, or business models.

AI is a powerful assistant but a poor navigator.

I’ve seen Product Owners who let the AI do most of the heavy lifting only to discover later that the product had wandered off course. It’s an example of how AI can be a powerful assistant but a poor navigator.

Scrum Masters: Moving From Framework Guardians to Collaboration Coaches

For years, I’ve believed the Scrum Master role would inevitably shift as teams become more experienced. As a team becomes proficient with Scrum, team members absorb some of the responsibilities of a Scrum Master.

AI is accelerating that shift. The future Scrum Master is less of a process guardian and more of a human dynamics expert. They will likely work across multiple teams, operate part-time on any single one, and spend far less energy worrying about prescriptive frameworks.

Instead, they will focus on helping people work well together. Asking tough questions, facilitating constructive disagreements, and guiding the team through difficult decisions—these human-centric skills will define the role. Scrum Masters and agile coaches who cling to checklists and frameworks will become less effective. Those who cultivate emotional intelligence, facilitation skills, and the ability to coach collaboration will become essential.

I’ve seen Scrum Masters who remain overly focused on rituals and mechanics while their teams quietly slide into dysfunctional communication patterns. In an AI-driven world, that approach simply won’t work.

Developers: More Productive Than Ever

Developers have also experienced extraordinary leaps in productivity. AI helps them generate code, uncover bugs, explore architectural patterns, and write tests. This enables them to accomplish far more in less time. And with that increased capacity comes a shift in team design. Many products that previously required teams of eight might now effectively be built by teams of four or five.

This shift also changes how teams think about specialization. We will still need world-class experts for highly specialized problems, but many teams will rely on strong generalists who possess broad skills and deep AI fluency. It also means that developers—moving faster than ever—must communicate more frequently to avoid stepping on each other’s work.

AI accelerates their capabilities. Human alignment ensures those capabilities don’t create chaos.

The Future of Agile Teams: Smaller, More Fluid, and More Global

All of these changes point toward a future where agile teams look different than they did even a few years ago. I expect teams to become smaller and more fluid. In many organizations, “team membership” will include a stable core supplemented by temporary specialists who join for a few weeks or months to work on highly complex tasks before moving on.

Teams will also continue to become more globally distributed. The “work from anywhere” movement has only strengthened, and AI will make collaboration across time zones easier.

Yet despite these changes, the definition of a team should remain simple: a team is a group of identifiable people pursuing a shared goal. That definition still holds, even when membership becomes more fluid.

As AI lowers the cost of experimentation, teams will attempt more ideas, pursue more niche products, and pivot more quickly. This makes leadership more—not less—important. Leaders must provide direction, so experimentation does not devolve into chaos. They must set strategic intent, define boundaries, and articulate a North Star that teams can use as an anchor.

Essential Collaboration Practices Every AI-Enabled Agile Team Must Protect

Since AI accelerates work, the practices that hold teams together become even more essential.

Sprint Reviews Are Now Critical Alignment Moments

The Sprint Review is one of them. As AI speeds up delivery, ensuring alignment between what the team builds and what stakeholders expect becomes absolutely critical. Only through real human feedback—and the interpretation of that feedback—can teams ensure that AI-accelerated work remains on target.

Backlog Refinement Needs Human Judgment, Even When AI Assists

Backlog refinement is another practice that must remain human-led. AI can draft backlog items or propose ways to split stories, but only humans can decide if those items contain the appropriate amount of detail, whether the intent is right, and whether each aligns with the product vision.

Daily Communication Becomes More Important, Not Less

Daily communication becomes essential as teams move faster. That communication doesn’t need to be in a formal meeting—many teams will choose asynchronous check-ins rather than a traditional daily scrum—but the keys are frequency and consistency. When a team can build features in hours, they need to talk about what they’re doing more often, not less.

Iteration Planning Ensures Shared Understanding in a High-Speed World

Iteration planning is similarly indispensable. Even if AI assists in forecasting, the team must still align on intent and understand how their work fits together. Planning keeps the team grounded in shared understanding.

The common thread is simple:

AI accelerates work; collaboration prevents accelerated mistakes.

Teams that reduce collaboration as AI usage increases will eventually undermine the very speed they're trying to gain.

How Leaders Can Evaluate Whether AI is Helping or Hurting Their Teams

Leaders often ask how they’ll know whether AI is helping or hurting their teams. The answer doesn’t require a dashboard full of metrics.

Are team members communicating more frequently than they did before AI?

If communication is decreasing, collaboration is weakening—and teams are heading into danger.

The faster the team moves, the more essential communication becomes.

What Agile Leaders Should Measure (And What They Should Stop Measuring)

AI does not fundamentally change the metrics that matter. Time to value still matters. The speed at which teams learn and adapt still matters. Customer outcomes still matter.

What leaders should avoid is the temptation to find a single productivity metric that magically reveals team performance. AI won’t create that metric. It isn’t coming.

Leaders should instead evaluate how quickly their teams can experiment, learn, adapt, and deliver results in alignment with customer needs.

Update Agile Principles for the AI Era

One of the original Agile Manifesto principles is “responding to change over following a plan.” In an age where AI makes experimentation incredibly cheap, I would take that a step further. Today’s agile teams shouldn’t merely respond to change—they should create it.

AI gives teams the tools to explore possibilities proactively, not reactively. It allows them to test ideas quickly, pivot when necessary, and discover value faster than ever. But that only works when collaboration and alignment remain strong.

A Warning—and a Call to Action

If leaders misunderstand AI’s role, they may believe collaboration is optional or that teams don’t need to talk as much. They may assume AI can take over decision-making or that agile roles matter less.

The result will be teams that drift apart, lose alignment, and make faster—but worse—decisions. The real danger of AI is not the technology itself but how teams behave when they believe it can replace the human elements of teamwork.

And so, the call to action is clear:

- Invest in human skills.

- Strengthen collaboration.

- Protect agile practices that make teams effective.

- Support Scrum Masters as they evolve into true collaboration coaches.

- Help Product Owners retain ownership of vision and strategy.

- Use AI as a partner, not a replacement for teamwork.

AI makes individuals faster. Only teams make products great.

Rethink the Refinement Session: Less Time, Better Outcomes 18 Nov 6:00 AM (last month)

If your team feels like it’s spending too much time in their backlog refinement meeting, they’re probably right. In my experience, more time is wasted in refinement sessions than in all other meetings combined.

The problem isn’t with refinement itself, but how some teams approach it. To fix it, start with the purpose of refinement. (For more on the purpose of all the Scrum meetings, read “Do Scrum Teams Meet Too Much?”)

Prefer to watch instead of read? In this short video, I walk through why most teams spend too much time in refinement sessions—and how to fix it.

The Purpose of a Refinement Session

The purpose of refinement is simple: To ensure that the items near the top of the product backlog can likely be completed in the next iteration.

That means those items need to be:

- Small enough to finish in a single iteration, and

- Sufficiently understood that the team can start work with confidence.

Let’s explore what that means.

Small Enough to Fit

“Small” is straightforward. The team can’t take a large backlog item into an iteration and expect to finish it. Most teams set a maximum size limit for any item they bring into an iteration. I recommend no more than half of the team’s velocity.

For example, if your team’s velocity is 20, you might allow an 8-point item into the iteration, but not a 13-point one. Ideally, items are even smaller—but half the velocity serves as a good upper limit when needed.

“The Goal Is Confidence Not Certainty”

Sufficiently Understood (But Not Perfectly)

Sufficiently understood means that enough is known about an item to bring it into the next iteration. It does not mean that everything is understood about an item.

The goal in any refinement session is to reach a point where the team feels confident they can probably complete the item within the iteration. Teams aren’t aiming to eliminate all uncertainty; they just need to reduce it to a level where they feel comfortable starting.

In fact, I want teams to end refinement thinking,

“We’ve resolved the big issues and enough small ones that we’re confident we can finish this.”

not

“We’ve discussed this so thoroughly that there’s nothing left to learn.”

There’s a balance between preparing enough and over-preparing. Often, it’s faster to start the work and let some discovery happen inside the iteration as team members overlap work and collaborate.

A little discovery during development is a feature of agile project management, not a flaw.

The Cost of Over-Refinement

When teams try to resolve every open issue during refinement, sessions drag on unnecessarily. You end up with the entire team sitting through detailed discussions that involve a few members.

It’s not just inefficient, it’s frustrating. No one wants to be stuck in a meeting where most of the conversation doesn’t apply to them.

So how do you make refinement sessions shorter, more productive, and less painful? Here are three ways.

1. Treat Refinement as a Pre-Planning Checkpoint

Think of your backlog refinement meeting as a pre-planning check, not a deep-dive workshop.

You don’t need to rename it but you should reframe it. The goal is to quickly review the top backlog items and confirm they’re ready for the next iteration.

This often includes splitting stories, estimating items that have risen in priority, or adding just enough detail for clarity.

These quick adjustments help ensure backlog items are small enough and ready—without turning refinement into a problem-solving marathon.

2. Stop Aiming for “Perfect” Understanding

Remind the team that refinement is not about certainty—it’s about readiness. Encourage your team to ask this one question often:

“Do we know enough about this item that we can probably finish it during the iteration?”

The phrase probably finish it encourages just enough analysis without overdoing it. It keeps discussions focused on what’s essential and reminds everyone that you don’t need 100% clarity before moving forward.

3. Consider Involving Only Part of the Team

While I generally support whole-team involvement in agile activities, backlog refinement can be an exception. You can get nearly the same value with fewer people—and in much less time.

Having about two-thirds of the team participate is often sufficient. You’ll hear nearly all the same questions and surface the same uncertainties without pulling everyone away from their work.

Rotate participation so that over time, everyone stays aligned. If someone consistently can’t attend, raise it in a retrospective.

This flexible approach keeps the process collaborative and efficient.

The Bottom Line

Backlog refinement sessions should help your team prepare for the next iteration, not wear them down before it starts.

When you treat refinement as a quick readiness check, focus on “sufficiently understood” rather than “perfectly defined,” and involve only the people who need to be there, you’ll cut the time dramatically without losing effectiveness.

Key Takeaways

- Refinement sessions are for readiness, not perfection.

- Items should be small enough (no more than half team velocity).

- Aim for “sufficiently understood,” not “completely known.”

- Use refinement as a quick pre-planning check, not a problem-solving meeting.

- Not everyone needs to attend every time.

Refinement sessions don’t have to be a drag. With a little rethinking, they can become one of the most valuable—and least painful—meetings of your sprint.

Want to help your team spend less time in meetings and more time delivering value? Explore our Meeting Observation and Recommendation Workshops. These short, focused engagements put our experts inside your Scrum meetings to observe and offer tailored insights for improvement.

How To Coach Your Team to Run Daily Scrum Meetings Themselves 6 Nov 8:22 AM (last month)

The daily scrum is likely the most misunderstood event in Scrum. The short 15-minute daily scrum meeting can be either the fuel that drives a team’s collaboration each day or the bane of the developer’s daily existence.

Taking a back seat is one of the most important things a Scrum Master can do to help their team get the most from this event. All too often Scrum Masters become the center of attention during daily scrums, which can lead to a whole host of dysfunctions. The Scrum Guide says this activity is “for the developers,” so it’s important that Scrum Masters coach their teams into taking ownership of this activity as soon as possible.

Daily Scrums Should Run More Like Parties

Imagine you’ve invited friends over for tacos and drinks. No one is going to run this little party. No one is controlling each conversation, where people stand, or how much guacamole someone eats.

The party runs itself.

The daily meetings of high-performing agile teams should run themselves as well.

Although that may sound easy, it’s not. Many subtle decisions you make along the way will point a team toward ownership of this event or let them fall back knowing that you are in charge instead.

New Teams Need More Help

In the beginning, Scrum Masters will need to coach their teams to reach a point in their maturity where the team can function independently at daily scrums. If a team is new to agile, it’s fine for someone—usually the Scrum Master or coach—to run the meeting.

Teams also will likely need help setting up their rules and norms. These might be that the meeting never takes longer than 15 minutes, that lengthy problem-solving is done after the meeting, and that the meeting happens at 10 AM online. Similarly, most teams establish a pattern of discussing progress, plans, and problems—the 3 Ps.

And for new teams, it's perfectly normal for the Scrum Master to call on people and instruct them to provide an update on their progress since the last meeting, their plan through the next meeting, and any problems their facing.

After all, new team members won’t know what to discuss in a daily meeting until they’ve had this explained and have experienced a few meetings. But team members will quickly figure it out, and when they do, it's time to coach them off of a Scrum Master-run meeting.

Three Things to Stop Doing So Teams Can Take Over

The best agile teams sync up successfully without someone running the daily meeting, much like having friends over for tacos. The meeting is not run by a Scrum Master, coach, product owner, manager, or anyone else. To get a team to the point where they are fully running the meeting themselves, successively stop doing three things.

- Stop asking questions

When the Scrum Master asks the questions, it naturally makes the Scrum Master the audience for the answer. Teams need to understand that daily scrums are not status reports to the Scrum Master. They are meetings for the team to plan with one another.

So the first thing to do is stop asking questions like, what progress did you make yesterday? or what is your plan for today? If a team member forgets to answer one of the team’s agreed-upon questions during their turn, just that one question of the person. - Stop calling on people

After perhaps a week like this, stop calling on people, too. Leave it up to the team members to figure out who goes next. You might call the meeting to order: “OK, it’s 10 o’clock. Let’s get started.” And then wait for someone to get things rolling.

If someone asks who should go first, tell them that’s up to them. They can go alphabetically, east to west geographically, randomly, or however they choose.

Too many Scrum Masters continue to call on people to speak next in the daily scrum, long after the team is ready to figure it out for themselves. When this happens, the developers wait for their turn until called upon. Crosstalk is limited, as is true collaboration.

The subtle act of simply calling on people can imply authority and might therefore lead to a misunderstanding that the Scrum Master owns this meeting and benefits from it.

If a developer still provides their update to you, even if you didn't initiate the question or call on them, be ready to redirect them back to the other developers. When in person, this might look like staring at your shoes and refusing to make eye contact. You might also try placing the rest of the team in a circle while you stand outside it.

When remote, try turning off your camera when that person is speaking, to help them get the message. Remote or in person, you might even arrange an “emergency that needs your attention,” giving you an excuse to duck out of the meeting. Anything to help the rest of the team understand that they need to be talking to each other, not at you. - Stop Starting Meetings

The next step is to stop starting the meeting. Instead of saying, “It’s 10 o’clock, let’s get started,” wait for someone else to do that.

Normally if people are used to you calling the meeting to order, they’ll just stare at you until you do. So you’ll probably need to tell them the first couple of times that it’s their meeting and they can decide when to get it started.

The sooner you can turn over control to the developers, the better. Encourage them to experiment with the format and try new things. If daily scrums aren't working to engage the team, the team might consider breaking out of the person-by-person approach to daily scrums. They can experiment with a story-by-story approach to daily scrums instead.

Your team has to find out what works best for them—it may be different from any other team. Show them what self-organization looks like and give them the power to take full control of their event.

Test Yourself

Here’s a challenge: Imagine someone is observing your daily meeting. From just that meeting would they know who is the Scrum Master, coach, or team lead? They shouldn’t. (Want an expert insight into your agile practices? Consider bringing us in for a Meetings Observation and Recommendations workshop. It's a small investment that can yield big results.)

It's true that Scrum Masters should guide teams through their early daily scrums. Later, they'll help when team members talk too much. Or when team members won't talk at all. But as time goes by, Scrum Masters, coaches, and team leads should turn more and more of it over to the team themselves.

Team-led daily scrums are a unique opportunity to nurture a team’s self-organization while simultaneously helping the team to get the most out of this event every day.

Your teams may not even know to thank you for it...and that’s OK.

Iterative vs. Incremental Development: Why Agile Teams Need Both 24 Sep 9:59 AM (2 months ago)

Agile frameworks like Scrum are built on two fundamental principles: iterative development and incremental development. These terms are so frequently used (and misused) that their impact can be lost, but understanding how each approach works—and why combining them is so powerful—is key to building better software, faster.

This article breaks down each approach, uses real-world analogies, and explores why the combination is more effective than either one alone.

What Is Iterative Development?

An iterative process makes progress through refinement.

An iterative approach to work starts with a rough version of a feature or product, then improves it through repeated cycles—each one getting closer to the final form.

For example, a sculptor who approaches work iteratively might begin by roughly carving a block of stone. With each pass, they would refine the form—adding details, smoothing edges, and continuously improving until the sculpture reaches its final shape. The sculpture isn't done until the whole piece is complete.

What Is Incremental Development?

An incremental process builds and delivers features and products in pieces. Each piece, or increment, represents a complete subset of functionality.

Increments may be either small or large. The focus is on finishing each increment of functionality in its entirety before moving on to the next, with no need to go back and revisit that work later. Each completed increment can be released on its own.

Returning to the sculpting analogy, an incremental sculptor would pick one element of the sculpture and focus on it until it’s finished. They may select small increments (first the nose, then the eyes, then the mouth, and so on) or large increments (head, torso, legs and then arms). However, regardless of the increment size, the incremental sculptor would attempt to finish the work of that increment as completely as possible before moving on.

Agile Teams Combine Incremental and Iterative

Agile development combines both approaches to get the best of both worlds:

- It's iterative because the plan is for each piece to be refined and improved over time.

- It's incremental because usable pieces of working software are delivered throughout the project.

This blend allows teams to deliver value early, get feedback, and adapt.

The video below demonstrates how comedian Jerry Seinfeld approaches his work in a way that is also both incremental and iterative.

Real-world Example: Building a Dating App

Imagine you're developing a dating website. Here's how each approach would work:

Purely Iterative

- Build and a little bit of every feature—profiles, search, chat, etc.

- Go back and enhance each one across multiple cycles.

- Over time, the entire system is perfected and then, finally, delivered.

Purely Incremental

- Build and deliver a perfect version of the profile management feature. Don't start on anything else until this is finished.

- Build and deliver a perfect version of a second area, say search. Then move on to the next.

- Each feature is perfect before the next begins.

Iterative + Incremental (Agile)

- Start with a basic version of the user profile, ship it. Get feedback.

- Add the ability to add a picture to the user profile and ship a basic version of search functionality. Get feedback again.

- Reorder the fields on the user profile to improve the user experience. Add filters to the search functionality. Create a wireframe of the chat feature. Get more feedback.

- Subsequent sprints might include enhancements to previous features and releases of new, usable functionality. Or both.

An agile approach allows early releases, low-risk experimentation, and frequent course corrections—hallmarks of high-performing teams.

Agile Is Iterative and Incremental

Neither incremental development nor iterative development brings much value alone. But together, they form the backbone of agility.

Iterative helps teams refine and adapt. Incremental ensures steady progress and value delivery. Combined, they enable agility, responsiveness, and real-world results.

The Five Pillars of a Successful Agile Transformation 29 Jul 6:00 AM (4 months ago)

An agile transformation is the ongoing process of adopting agile values, principles, and practices to improve business outcomes. Successful agile transformations result in cost savings, improved customer satisfaction, and faster time to market.

Agile transformations don't succeed by accident. Sustainable change takes time, effort, commitment, and planning.

Most organizations know this, so they invest in training, roll out new tools, adopt Scrum or another framework, and perhaps bring in agile coaches. Some organizations start small, with one or two teams so that they can uncover challenges and learn from their experiences before expanding their effort. Others go all in, transitioning many teams at once. (Read more about this in "Choosing to Start Small or Go All In When Adopting Agile.")

These are all steps in the right direction but they’re not enough on their own.

For the past two decades, we’ve worked closely with teams in every kind of environment—from tightly regulated industries to fast-paced startups—and across products, platforms, and services. We’ve seen what gets in the way and what engenders transformation.

In our experience, sustainable change depends on five essential pillars: mindset, practices, roles, teamwork, and support. When even one of these pillars is missing or neglected, progress stalls. But when all five are reinforced, an agile transformation can thrive.

Let’s take a closer look at each one.

Pillar One: Mindset - Think Agile to Be Agile

At its heart, agile is a way of thinking. An agile mindset embraces change, values collaboration, and views failure as a learning opportunity. Without this mindset, people might go through the motions of an agile framework like Scrum without ever truly benefiting from it.

Mindset change is one of the most common challenges we hear about. In our survey of agile practitioners, this typical comment highlights the barriers:

“It’s difficult to shift people's mindset from delivering a big bang solution to delivering iteratively.”

Another noted:

“Leadership says we’re agile, but they still demand the same old waterfall deadlines.”

Others described the challenge this way:

“Teams are ‘doing agile’ but don’t believe in it. They still think of change as failure.”

If you’re championing an agile transformation, it’s critical that everyone understands why they are working differently. That understanding empowers them to make better decisions in ambiguous situations. It also means they’re more likely to respond well to uncertainty or obstacles.

Problems with an agile transformation when mindset is ignored

You might hope that once a handful of agile practices are in place, an agile mindset will seep in all by itself. In my experience, this isn’t the case. For your agile transformation to succeed, you need to consciously establish the new way of thinking.

Without a concerted efffort to explain why new practices are in place, progress stalls. People disengage, see the agile transformation as an external imposition, and lose the willingness to inspect and adapt. Over time, trust erodes between team members and between teams and leadership.

In this kind of environment, any gains quickly become temporary as people revert to old ways of working.

Warning signs that your agile transformation is in trouble

We often see organizations where agile has been implemented unevenly. Some parts of the business strictly follow Scrum, others think they're agile because they use Jira. This inconsistency in what it even means to be agile leads to confusion and disillusionment.

Improvements to try now

To build alignment, try inviting individuals to share stories of what agility looks like when it’s working well. Or run a simple retrospective-style session where people list behaviors that feel agile and those that don’t. When you surface differences in interpretation, you create the opportunity for meaningful discussion—and practical improvements.

You’ll find more ideas in this post: How to Get Teams Aligned on What It Means to Be Agile

Pillar Two: Practices - Put Agility Into Action

If mindset gives you the why behind an agile transformation, practices give you the how. User stories, backlog refinement, sprint planning, and iterative, incremental delivery are the day-to-day tools of agile teams.

Agile practices help agile teams plan, collaborate, and deliver effectively. When done well, they increase transparency, expose risks early, and foster alignment.

Respondents to our agile challenge survey were clear about where things go off track.

One wrote:

“We don’t know how to break stories down small enough to finish in a sprint.”

Another shared:

“Backlog refinement is inconsistent and often skipped due to time constraints.”

And perhaps most tellingly:

“Planning takes hours and still no one knows what they’re working on Monday morning.”

Problems with an agile transformation when practices are ignored

Without implementing new practices, people tend to operate largely as they did before, creating an organization that is agile in name only. More than that, poor agile practices create a lack of visibility. Work piles up unfinished, quality suffers, and feedback loops break down. Even motivated teams struggle to deliver consistently without practical tools that support agile ways of working.

Warning signs that your agile transformation is in trouble

It's usually easy to tell when you are struggling with one or more agile practices. The challenge comes in identifying exactly where the problem lies and how to address it. Here are just a few of the common issues we see:

- Daily Scrum: The daily scrum becomes a status report to the Scrum Master rather than a collaborative planning session for the day.

- Sprint Length: Sprints are too long to create a regular cadence, or too short to finish meaningful work.

- Sprint Planning: People emerge from planning unclear on the goal or overcommitted on scope.

- Writing Stories: Stories are too large or vague to complete in a single sprint.

- Retrospectives: People repeat the same surface-level observations in every sprint retrospective without addressing root causes.

- Siloed Work: Work does not overlap: design is fully done before development, and development is finished before testing begins.

- Estimating: Agile estimation becomes a painful debate or is skipped entirely, leading to unpredictable delivery.

Mountain Goat Software offers training and mentoring on many of these specific topics, from writing better stories to facilitating more effective retrospectives.

Improvements to try now

Training and coaching should happen in conjunction with assessments to address skill gaps and support the continuous improvement needed for sustainable and effective transformation. Mountain Goat offers free resources and tools to help assess the specific practice issue that’s holding you back:

Elements of Agile is a free assessment tool designed to help you evaluate how well your team or organization is progressing toward agility. It identifies strengths, highlights areas for improvement, and provides a clear report so you can focus your efforts where they’ll make the biggest impact.

The Personalized Guide to Agile is free, customized report that recommends practical steps to improve your agile practices based on your unique goals and challenges. Complete a short quiz and receive tailored resources to help you work more effectively.

A free video series that provides a solid overview of the key Scrum practices and how they work together.

Continuous improvement is a key agile tenet, one that frequently requires continuing education. The free Mountain Goat ROI calculator helps you estimate the return on investment from agile training by comparing potential benefits against costs. It includes calculation guidance, key metrics, and success stories so you can confidently assess the value of your investment in training.

Pillar Three: Roles - Clarify Who Does What

Agile introduces new roles and redefines existing ones. New roles like Scrum Master, product owner, agile coach, and even Scrum team member (developer) bring new responsibilities and shift old ones. But without clarity around the boundaries of these roles, transformation stalls.

In the words of one practitioner:

“We have a PO, but everything still goes through the VP.”

Another added:

“Nobody really knows what the Scrum Master is supposed to do, so they just schedule meetings.”

And a third summed it up this way:

“Too many cooks in the backlog.”

Problems with an agile transformation when role clarity is ignored

If roles are not clarified, people will be confused about their responsibilities. This creates bottlenecks, with important work delayed while people wait for approvals. Alternatively, decisions are made but are made inconsistently. When roles are fuzzy, accountability also suffers, and with it, trust and velocity.

Sometimes a transformation stalls just because people are unsure of who should be doing what, not because people aren’t bought in or working hard.

Warning signs that your agile transformation is in trouble

Role confusion can look like: unclear authority over the backlog, people bypassing the Scrum Master, or multiple stakeholders giving conflicting directions. Sometimes people step into agile roles with leftover expectations from traditional hierarchies, or never land on a shared understanding of who is responsible for what.

Improvements to try now

You can improve alignment by doing the following three things:

Clarify roles and responsibilities

Ensure everyone understands their role. For example, the product owner is responsible for prioritizing the backlog, the Scrum Master facilitates the process, and the team of developers self-organizes to deliver the work. Misunderstandings often stem from unclear expectations.

Encourage self-organization

Self-organizing teams are empowered to make decisions about how they work, within a set of shared values and rules set forth by management. If people are hesitant to decide, resist stepping in to make decisions for them. Instead, reiterate that the decision is theirs and support them in their choice.

Facilitate communication

If multiple stakeholders or businesspeople are providing conflicting priorities, work to establish a single source of truth, such as a clear roduct owner. Encourage stakeholders to resolve conflicts among themselves before bringing priorities forward.

Clear role definitions will increase alignment and reduce friction. When everyone understands who’s accountable for what, people feel empowered to act decisively and deliver value, improving morale and productivity. For an introduction to the Scrum roles and responsibilities, visit: https://www.mountaingoatsoftware.com/agile/scrum/roles

Role Clarification Resources

Would you make a good Scrum Master?

Would you make a good Scrum Master?  How to become a great product owner

How to become a great product owner  Clarifying Cross-Functionality

Clarifying Cross-FunctionalityPillar Four: Teamwork - Collaborate to Deliver

Success with an agile transformation depends on how effectively everyone (including developers, testers, UX designers, analysts, and so on) works together to deliver value. In other words, success requires teamwork and agile collaboration.

Effective agile teamwork enables fast delivery, and continuous improvement. When people collaborate effectively, they complete stories within short iterations and adapt quickly to change.

But it’s not always easy to just ‘work well together.’ We heard from practitioners who weren’t seeing successful collaboration within a Scrum or agile framework:

“We still hand off work between developers and testers like we did before agile.”

“Our team is remote and barely talks outside of standups.”

“One or two people carry the sprint every time.”

Problems with an agile transformation when teamwork is ignored

Without improvements in teamwork, organizations will see limited gains. People fall into silos and work becomes sequential, making knowledge-hoarding more likely. Over time, this can lead to burnout and disengagement.

You may find that people are hitting a wall with their delivery pace, and no amount of process change or overtime is helping to improve the situation.

Warning signs that your agile transformation is in trouble

Common breakdowns include work done in isolation instead of shared ownership, with a feeling of “I’ve done my part, now it’s their turn.”

People might delay testing until the end of the sprint. Certain individuals may consistently do most of the work. Or people may have a general sense that they work well together but struggle to pinpoint what that looks like in practice.

Improvements to try now

To improve collaboration, start by making work visible and ensuring goals are shared. Try swarming: get two or three people working on one story at the same time to build shared ownership. Look for ways to reduce handoffs and encourage knowledge-sharing.

If you're not sure what to change, consider using the traits of high-performing agile teams as a discussion tool: What Is a High-Performing Agile Team?

Pillar Five: Support - Gain Buy-In Beyond the Team

The fifth pillar of transformation is often the most overlooked: how others—leaders, stakeholders, adjacent departments—interact with and support agile teams.

Leadership buy-in and engagement at all levels is essential for a successful agile transformation. Strong agile leaders foster a supportive culture in the following ways:

- Allocate resources

- Set the vision

- Communicate the goals for agile transformation

- Celebrate achievements, big and small

- Alleviate resistance to change at all levels of the organization.

Even the most agile of teams will struggle if the surrounding organization operates with old assumptions. If stakeholders demand delivery dates without negotiation or leaders expect certainty instead of adaptability, teams face an uphill battle. For example:

“Stakeholders expect exact dates but don’t come to reviews or refinement.”

“We’re agile, but leadership still thinks in terms of big up-front plans.”

“Changing priorities are dropped in, mid-sprint by senior leaders with no discussion.”

Problems with an agile transformation when support is ignored

Without adequate support and understanding, team members become frustrated from being pulled in too many directions. Stakeholders see only missed expectations. Product owners become order-takers instead of collaborators. Over time, people may start to hide issues or disengage entirely. As a result, the agile transformation becomes a source of tension not improvement.

Warning signs that your agile transformation is in trouble

One of the most common breakdowns is expecting predictability without participation. Leaders may want reliable delivery, but if they skip reviews and avoid refinement sessions, they rob the team of alignment. Similarly, if estimates are misunderstood as commitments, teams can feel pressured to inflate numbers or pad buffers.

Improvements to try now

To reset expectations, involve stakeholders early and often. Encourage stakeholders to attend reviews, not just as a ‘demo,’ but to ask questions and give feedback.

Try to foster a team mentality: Frame challenges, such as tight deadlines or scope issues, as shared problems. Encourage collaboration between the team and stakeholders to find solutions that balance business needs with the team’s capacity.

If estimation is a contentious issue between the team and stakeholders, consider reviewing how your teams talk about and use estimates. Are estimates helping or hurting team focus? They can sometimes help developers make trade-offs but sometimes they cause more confusion than clarity. For more, read: Are Estimates Ever Helpful to Developers?

Start Where You Are. Improve Iteratively.

No agile transformation begins with everything figured out. That’s why we encourage iterative and incremental improvement to continuously identify and pursue changes that will make work less cumbersome and more efficient.

Use the five pillars to assess where your organization is today in its agile transformation, and decide where to focus next. Each improvement you make supports the others. That’s how real, lasting agility takes hold.

Ready to Put These Five Pillars into Practice? If your team is struggling with misalignment, inconsistent results, or stalled progress, our Working on a Scrum Team course can help.

In just two live, online days, your team will learn side-by-side through interactive exercises and real-world scenarios, leaving with a shared understanding and practical tools to succeed.

Bring your whole team, or a few key change-makers, and return ready to deliver every sprint. Read more about the course and register here.

Self-Organizing Teams, their Benefits, and a Leader’s Role 15 Jul 7:03 AM (5 months ago)

Self-organizing / self-managing teams are a cornerstone of agile project management but they’re often misunderstood. Many mistakenly believe these agile teams operate without structure or guidance. Nothing could be further from the truth.

This article explores what self-organizing teams are, how leaders can support them effectively, and the powerful outcomes that emerge from self-organizing teams.

What Are Self-Organizing Teams?

A self-organizing (aka self-managing) team is one that has the ability and autonomy to determine how best to accomplish its work within the boundaries and constraints put in place by its leaders.

Self-organization doesn’t mean the team is unmanaged or anarchic; it means the team organizes itself around tasks, responsibilities, and collaboration.

In the chapter “Seven Leaders for Guiding the Evolving Enterprise” from Clippenger’s The Biology of Business, contributor Philip Anderson addresses some of the misunderstandings about self-organization:

“Self-organization does not mean that workers instead of managers engineer an organization design. It does not mean letting people do whatever they want to do.

“It means that management commits to guiding the evolution of behaviors that emerge from the interaction of independent agents instead of specifying in advance what effective behavior is.”

Self-managing agile teams have two types of authority: They have authority over 1) their work and 2) the process they use. They do not have authority over who is on the team or the team’s purpose.

For more on how self-organizing teams fit into Richard Hackman's authority hierarchy, read "Two Types of Authority Leaders Must Give Self-Organizing Teams."

Self-Organizing Teams Take Ownership

The idea behind fostering self-managing teams is that teams are encouraged to fully own the problem of performing their work.

Self-organizing teams prioritize collaboration over individual efforts. That’s one reason the daily scrum is such an important part of a Scrum team’s success: it allows all the team members to coordinate daily on how they will meet their goal, and self-organize to solve problems when something could impede their plan.

Self-organization implies that not every agile team will choose to organize themselves the same way, and that’s OK. For example, consider an agile team trying to problem-solve who should make key technical decisions.

Some teams might decide that one person will make all key technical decisions.

Other teams might decide to split decisions along technical boundaries: The database expert makes database decisions, but the most experienced Python programmer makes Python decisions.

Still other teams might decide that whoever is working on the feature makes the decision but shares the results with the team.

Self-management means the teams, not their Scrum Masters or managers, make these determinations.

Factors to Consider when Forming Agile Teams

A common concern about self-managing teams is “We cannot just put eight random individuals together, tell them to self-organize, and expect anything good to result.”

Well, I don’t know if we can put eight random people together and expect anything either, but I do know that an agile team should not be a random collection of people.

Self-organizing doesn’t mean randomly put together. Those in the organization responsible for initiating an agile project should expend a lot of effort in selecting the individuals who will comprise the team(s) for that project.

Here are five factors for management to keep in mind when structuring teams:

1. Include all necessary disciplines

Agile requires cross-functional teams, meaning they possess all the skills and expertise necessary to go from idea to implemented feature. Initially, this can lead to teams being slightly larger than desired.

That’s OK. Over time, individuals will learn some of their teammates’ skills as a natural result of being on a Scrum team. As some team members develop broader skills, others can be moved onto other teams.

2. Mix technical skill levels

Subject to considerations of team size, strive to balance skill levels on the team. If a team has three senior programmers and zero less-experienced programmers, the senior programmers will need to code some low-priority features that they could find boring.

Not only might a junior programmer have found such features enjoyable to work on, but that programmer would also benefit from learning through association with the senior programmers.

3. Balance domain knowledge

Strive, too, for a balance between those with deep knowledge of the domain in which you are working or the problem you are attempting to solve.

This is not to say that if you have the opportunity to assemble a team entirely of domain experts, you shouldn’t take it. Rather, consider the long-term goals of the organization.

One of those goals is likely building domain knowledge throughout the organization. You’ll have a hard time achieving that if you put all of the domain experts on one team.

4. Seek diversity

Diversity can mean many different things—gender, race, and culture being just three of them. Perhaps equally important is how individuals think about problems, how they make decisions, how much information they need before they decide, and so on.

Research shows that homogeneous teams reach consensus more quickly than heterogeneous teams, but unfortunately they do so by failing to consider all options.

5. Consider persistence

It takes time for agile team members to learn to work well together. Strive, therefore, to keep team members together who have worked well together in the past.

When forming a new team, consider how long members will be able to work together before some or all are dispersed to other commitments.

The Role of a Leader in Self-Organizing Teams

Another common misconception about self-organizing teams is that they don’t need leaders or managers. Leadership is crucial for agile teams—it just looks different from traditional command-and-control models.

A leader’s role in self-managing teams is to set appropriate challenges and remove impediments. Here’s a typical process for leading self-organizing teams:

- Define the vision and goals

- Ensure alignment with organizational strategy

- Remove obstacles that block progress

- Encourage team growth and learning

A manager’s role is to foster the environment in which self-organization can thrive. They act more as guides than bosses.

How to Lead Self-Organizing Teams without Undermining Autonomy

Self-organization is a critical capability that enables high-performing agile teams to deliver value frequently and quickly. Leading self-organizing teams effectively requires restraint and intention:

- Set a few clear boundaries and expectations. Teams need constraints to innovate effectively. But if you overly constrain them, you will impede self-organization and creativity. Prioritize.

- Encourage team ownership. Let teams take responsibility for decisions and results. The best Scrum teams are self-sufficient.

- Support rather than steer. Be available as a coach, not a taskmaster.

- Promote continuous improvement. Help teams reflect and adapt through sprint retrospectives and feedback loops.

Servant leadership is a helpful model here. Serve the team’s success by amplifying their autonomy, not replacing it.

Agile Leadership & the Art of Subtle Control

In the original paper describing Scrum, Takeuchi and Nonaka identified “subtle control” as one of its six principles. They list staffing decisions as a key management task.

“Selecting the right people for the project team while monitoring shifts in group dynamics and adding or dropping members when necessary [is key].

“‘We would add an older and more conservative member to the team should the balance shift too much toward radicalism,’ said a Honda executive. ‘We carefully pick the project members after long deliberation. We analyze the different personalities to see if they would get along.’” So how does someone achieve this kind of subtle control? Consider the following example.

An example of subtle control

Suppose you are a Scrum Master, coach, manager, or leader for a team. You noticed that one team member is consistently domineering and no one is willing to stand up to him.

This team has self-organized—consciously or not it has chosen to let one member make all key decisions. You recognize, though, that if one person continues to make all the decisions, it will impede the team’s efforts to improve.

You have a few options.

You could have a private conversation with the domineering team member. You might help them see that even in situations where they’re sure they know the “right” thing to do, they’ll learn by sometimes giving others a chance to express their thoughts before voicing their own opinion. You might also suggest they take care to present their thoughts as an opinion rather than as an unchallengeable decision.

You could enlist the team member’s assistance as a mentor to the others. Their job would be to sideline-coach the other team members, allowing them to practice such that they will make the right decisions on their next projects, where that domineering team member may not be there to make them.

If neither of those conversations work, you might go further, and change the team’s dynamics. Here are a few examples among the many ways to accomplish this:

- Ask management to add someone new to the team who is likely to stand up to the outspoken team member.

- Suggest that someone from the enterprise architecture group attend key meetings—someone with the experience, background, and propensity to challenge the team member.

The point is that no matter the specific problem, if the team has self-organized in a way that impedes team progress, you’ll need to find a way to agitate, stir up, or otherwise disturb the status quo so that the team adjusts and hopefully reorganizes in a more productive way.

What Emerges from Effective Self-Organizing Teams

One of the principles from the Agile Manifesto is “The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams.”

Well-formed and well-led self-organizing teams foster powerful outcomes:

- Innovation: Teams that own their process are more likely to experiment and find better solutions.

- Resilience: Self-management builds problem-solving skills and confidence.

- Engagement: Autonomy and purpose drive motivation.

- Speed: Decision-making is faster when teams don’t need top-down approvals.

These benefits aren’t automatic. They emerge when management invests in the conditions that allow self-organization to flourish.

There is more to leading a self-managing team than buying pizza and getting out of the way.

Teams don’t need their Scrum Masters, managers, and coaches to have all the answers. What teams need is for their leadership to create a space where agility can emerge organically.

More Help for Agile Teams

Working on a Scrum or agile team requires new skills and mindset shifts, for both the team and its leaders. Invest in development opportunities for team members to boost communication and collaboration.

If you want some help getting your team on the same page about agile and Scrum, our Working on a Scrum Team course is always available as a private course and is occasionally offered as a public course as well. Learn how to snag a seat for yourself, for your whole team, or for some subset of your team.

FAQs about Self-Organizing / Self-Managing Teams

What is the role of a leader in a self-organizing team?

Leaders and managers in self-organizing teams act as facilitators, not dictators. They provide clear goals, remove obstacles, support team development, and foster an environment where the team can take ownership of how work gets done. They don't direct work; they enable it.

Can self-managing teams succeed without leadership?

Maybe—but why would you try? Teams that self-organize to manage their internal processes still rely on leadership for direction, alignment with broader goals, and support. A lack of leadership often leads to confusion, misalignment, or stalled progress. Effective leadership may be subtle but it is essential for success.

How do self-managing teams make decisions?

They use collaborative decision-making, ranging from consensus to consultation to delegated authority within the team. Roles and responsibilities may shift dynamically based on expertise, availability, or team agreements.

Are self-organizing teams really more effective?

Yes, when thoughtfully formed and well-led. Self-organizing teams often deliver better innovation, faster results, and higher engagement. These outcomes emerge because agile team members feel accountable, empowered, and connected to their work.

How are self-organizing teams formed?

They are carefully assembled based on skills, experience, personality fit, and shared goals—a random group won’t work. Leaders play a key role in ensuring that the team composition supports self-organization from the outset.

Getting Better Estimates Is Easier Than You Think 10 Jun 7:04 AM (6 months ago)

The topic of estimation can be contentious. One big reason is that, when it comes to creating estimates for agile planning, people are simultaneously your greatest asset and greatest obstacle.

Better Estimates Are Built on Better Understanding

Estimating is a human task, and humans can be complicated. No matter how clearly you define and explain the process, estimates are influenced by bias, background, and individual perspectives. Even if you and your team understand the theory behind estimating with story points, if you don’t account for human nature and personality dynamics, you can still encounter problems.

I’m not saying your team members are problem people; I’m sure they’re awesome. It’s just that people bring baggage and preconceived notions to the estimation process.

How People Problems Cause Estimation Problems

A team's past experiences with estimation can contribute to future problems with estimation. For example:

-

That one person who won't budge on an estimate.

-

Those one or two people who appear to go along with the process, but aren't truly putting in the effort.

-

Those new team members who are uncertain about estimates, story points, or are intimidated by more dominant voices in the room.

-

That one hold-out who refuses to estimate anything that isn't in their skillset. (The article "3 Roles That Need to Be Involved with Agile Estimating" goes into why it's so essential for the whole team to participate in giving estimates.)

If you can’t wrangle your individual team members' hidden biases and opinions—not to mention varying areas of skill and experience—you’ll struggle to work as a cohesive team and produce accurate estimates.

Other Reasons Teams Avoid the Estimation Process

Many teams are also reluctant to estimate for fear of creating a plan that stakeholders will use against them.

Clients and stakeholders will always want to know what will be delivered and when, but it's difficult to predict this if the work is new or unfamiliar, especially if these same stakeholders are expecting perfection rather than accuracy. (One sure way to help is to ensure everyone is on the same page about what kind of estimate is being provided.)

Teams with a history of going through the motions of creating plans and estimates that they know lack accuracy just to check a box are likely to complain about providing any estimates at all. Those teams likely complain that they just want to get on with building something. (Here's why, despite their protests, estimates can be helpful to developers.)

Sound familiar? Many of the issues surrounding estimates stem from the belief that, as humans, we're just bad at estimating.

But that's not true.

People Are Good at Estimating Certain Things

People definitely struggle to estimate some things but others they're surprisingly adept at estimating accurately.

For example, later today I plan to write another blog post. I estimate it will take two hours to complete the first draft of that. It's unlikely to take exactly two hours but it will probably take between one-and-a-half and three hours. For the purpose of planning my afternoon, that's a good estimate.

(Read "5 Ways to Achieve Accurate Estimates Everyone Trusts" for more on why perfect is the enemy of good, including why it's best to express estimates as a range.)

Back when I was teaching in-person Certified ScrumMaster® courses, I would set up the room the day before. I would put a lot of supplies out for each person in the class. I had to hang some posters on the wall. And so on. From experience, I'd estimate that a typical room set-up would take 30-45 minutes. I've set up for so many Certified ScrumMaster courses that I feel fairly confident in that estimate.

There are probably a myriad of similar tasks that you find yourself estimating (successfully) most days—whether it's fixing dinner, driving to a friend's house, or going grocery shopping.

"We're good at estimating familiar things. Estimating unfamiliar things is harder."

We're pretty good at estimating these things because we have a certain level of familiarity with them. We're not as good at estimating things we aren't familiar with.

Proof That Software Estimates Are More Accurate Than They Seem

Data supports my claim that humans tend to estimate well.

In a 2004 review of the existing research on software estimates, University of Oslo professor and Chief Scientist at the Simula Research Laboratory Magne Jørgensen found most estimates to be within 20 to 30% of actuals. And on software projects, he did not find an overall tendency for estimates to be too low:

The large number of time prediction failures throughout history may give the impression that our time prediction ability is very poor and that failures are much more common than the few successes that come to mind. This is, we think, an unfair evaluation. The human ability to predict time usage is generally highly impressive. It has enabled us to succeed with a variety of important goals, from controlling complex construction work to coordinating family parties. There is no doubt that the human capacity for time prediction is amazingly good and extremely useful. Unfortunately, it sometimes fails us. –Magne Jørgensen

Busting the Myth That Software Projects Are Always Late

But if we're actually fairly good at providing accurate estimates, why is there a common perception that we are bad at it, especially when it comes to estimates on software projects?

One reason is that organizations tend to green light to underestimated projects far more often than overestimated projects. (This blog post reveals why teams underestimate and the #1 reason even agile projects are late.)

Scenario 1: The Underestimated Project

Imagine a boss who describes a new product to a team. The boss wants an estimate before approving or rejecting work on the project. Let's suppose the project, if played out, would actually take 1,000 hours. Of course, we don't know that yet, since the team is just now being asked to provide an estimate.

For this example, let's imagine the team estimates the project will take 500 hours.

The boss is happy with this and approves the project.

But…in the end it takes 1,000 hours of work to complete. It comes in late and everyone involved is left with a vivid memory of how late it was.

Scenario 2: The Overestimated Project

Let us now imagine another scenario playing out in a parallel universe. The boss approaches the team for an estimate of the same project. The team estimates it will take 1,500 hours.

(Remember, you and I know this project is actually going to take 1,000 hours but the team doesn't know that yet.)

So what happens?

Does the team deliver early and celebrate?

No. Because when the boss hears that the project is going to take 1,500 hours, they decide not to do it. This project never sees the light of day so no one ever knows that the team overestimated.

"Overestimated projects are less likely to get approved."

A project that is underestimated is much more likely to be approved than a project that is overestimated. This leads to a perception that development teams are always late, but it just looks that way because teams didn't get to run the projects they had likely overestimated.

Overconfidence Can Lead to Inaccurate Estimates

Although we're not necessarily bad at estimation, teams are definitely not as accurate as they could be. In my experience, this usually stems from an overconfidence in our ability to estimate accurately.

To help people see how this happens, I ask a series of ten questions in class. The instructions are simple: Provide the answer a range that you are 90% confident will contain the answer. I explain that no one needs to know the exact answer to provide a correct answer; the answer will be correct if it is accurate, if it falls in the range.

For example, I might ask estimators to estimate when the singer Elvis Presley was born: "Give me a range of years that you are 90% certain will contain the correct answer."

If the estimator is a huge Elvis fan, they'll know the year he was born. They might even know the exact date, and as a result, they wouldn't likely need to give a range of years to provide an accurate answer.

But most time, people don't know quite that much about Elvis. Their range needs to be wider because they are less familiar with what they are estimating. Remember, I want a range of years that people are 90% confident contains the correct year.

They might start by thinking, “Didn't he have some hit records in the fifties? Or was it the sixties?”

They might then think that if Elvis was recording at the age of 20, and had hits in the fifties, an early year of his birth could be 1930.

And at the upper range, if he was recording in the sixties, perhaps he wasn't born until 1940.

So they might come back with this estimate: Elvis was born from 1930–1940.

And in this case, they'd be correct, since Elvis was born in 1935.

The next nine questions deliberately ask for answers that might be more difficult to narrow down. For example I might ask how many iPads were sold in 2019, or how many athletes competed in the 2016 Olympics, or for the length of the Seine River.

Now, for each question, the parameters remain the same:

-

Provide a range of numbers (units/athletes/miles, etc.) that you think contains the correct answer.

-

Be 90% confident that the correct answer is within that range.

What happens is surprising! Even though I tell them to give me ranges that are 90% certain of, most people get most questions wrong.

"Even though I tell them to give me ranges that are 90% certain of, most people get most questions wrong."

The ranges they provide are usually much smaller than they should be when considering their unfamiliarity with the subject.

For example, let's imagine that I have no idea how many iPads were sold in 2019. If I want to be 90% certain the range I give contains the correct answer, I should provide a huge range, say zero to one billion. That would be widely exaggerated, but I'd be confident in my answer.

In my experience, the ranges people pick are narrower, suggesting that we overestimate our own ability to estimate accurately.

This is a simplified illustration, but there are a number of studies that suggest people are overconfident when it comes to forecasting.

The Secret to Getting Better, More Accurate Estimates

Data shows that individual estimators do improve when presented with evidence that their estimates are wrong.

In one study of software development work ("How Much Does Feedback and Performance Review Improve Software Development Effort Estimation? An Empirical Study"), researchers found that on the first ten items teams estimated, programmers were correct only 64% of the time.

When provided with feedback that their estimates were wrong, these same programmers improved to 70% correct on the second set of ten items. And then to 81% on the third set, after additional feedback on their accuracy.

It's clear that knowing how close estimates match reality can help you and your team improve at estimating projects.

Another way you and your team can get better at creating accurate estimates and plans is through training. Mountain Goat offers public and private estimating and planning training, as well as on-demand video courses, to help you and your team improve at creating agile estimates and plans.

I encourage you to explore all of our estimating and planning course offerings to find the one that works best for your situation.

Four Common Scrum Master Mistakes–and How to Fix Them 15 May 1:43 PM (7 months ago)

Being a Scrum Master isn’t easy.

Give a team too much advice, and they’ll start relying on the Scrum Master to make every decision. But don’t give enough, and the team’s growth will stall.

Solve too many problems yourself, and the team may start expecting you to fix every issue. Ignore some problems, and they might not even inform you about impediments.

Scrum Masters must walk a fine line, and it’s easy to slip up. In this post, I’ll cover four common mistakes Scrum Masters make and offer practical tips to overcome each one.

Mistake #1: Letting Work Spill Over into the Next Sprint

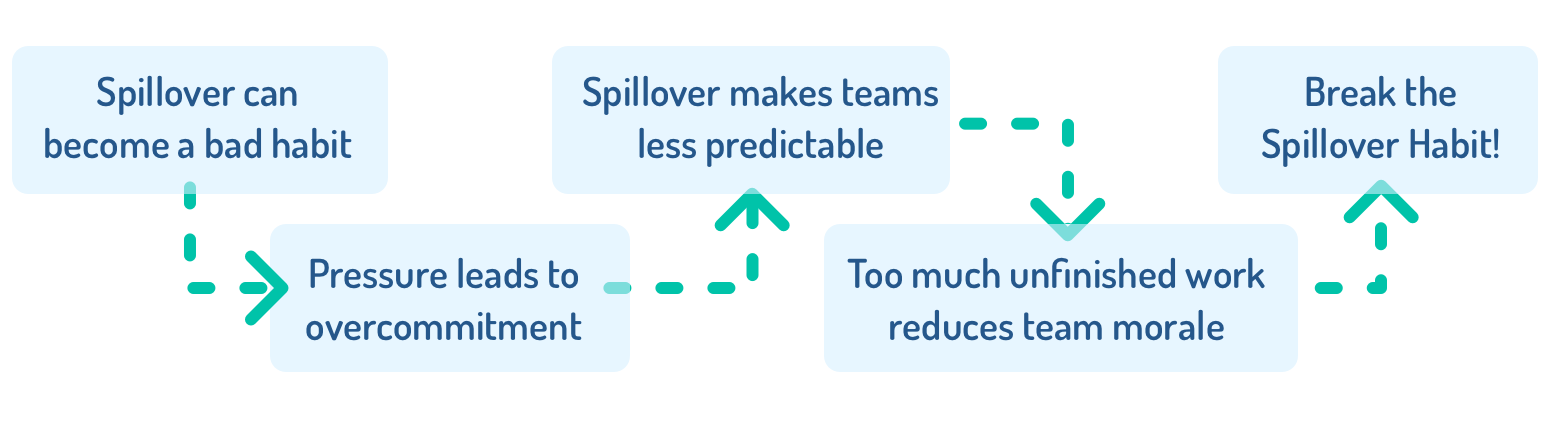

One of the worst habits a Scrum team can develop is allowing work to spillover from one sprint to the next. This happens when a team fails to complete all the planned backlog items and simply rolls them into the next sprint.

“A Scrum team shouldn’t take a cavalier attitude toward failing to finish.”

While it’s okay, and even desirable, to not finish everything, every time—it means the team is planning ambitiously—it shouldn’t become routine.

A Scrum team should not take a cavalier attitude toward failing to finish. If it does, sprints lose meaning, becoming arbitrary boundaries rather than clear cycles of work.

Teams should feel a slight sense of urgency as the sprint nears its end.

How to Fix Spillover

If spillover is a recurring problem for your team, try these two things.

First, break the habit by planning hyper-conservatively for the next sprint or two. Encourage the team to plan its next sprint such that they can definitely finish everything. Then, if they finish everything, they can add more to the sprint.

Next, highlight the occurrence and remind teams that habitually not finishing is a problem. One way to do this is to bring it up in retrospectives and ask them to discuss why it happened.

I’m not suggesting that you make them feel bad or demoralized. I only want them to feel as concerned as I do right now. I’m trying to cut down on soda. I’m making progress and haven’t had any for a week. But today I just felt like having a soda while writing this. So I did.

I don’t feel guilty, but I’ll just make sure I definitely don’t have another tomorrow as I don’t want to get back in that habit.

Learn more in Spillover in Agile: 3 Ways to Break the Unfinished Work Habit.

Mistake #2: Running the Daily Scrum

A second mistake I see Scrum Masters make frequently is running the daily scrum meeting. While it's important for the Scrum Master to participate and give an update, they should not take on the role of conducting the meeting (for example, calling on people to speak).

Daily scrums do not need a traffic cop calling on people. When a Scrum Master runs the meeting that way, the discussion becomes too directed at the Scrum Master. A daily scrum is not a status meeting solely for the benefit of the Scrum Master!

“Ideally, an outsider observing should not be able to immediately tell who the Scrum Master is.”

It’s normal when a team is first getting started for the Scrum Master to take a more active role in the daily scrum. However, the goal is for the team to fully own the meeting. Ideally, an outsider observing should not be able to immediately tell who the Scrum Master is. While there may be occasional guidance, the Scrum Master shouldn’t dominate the meeting.

The Fix for Running the Daily Scrum

I like to start a new team by leading the first two or three meetings. Then, I transition to simply saying, 'OK, everyone, it’s time to start,' maybe prompting with 'Who wants to go first?' Soon after, I stop saying even that.

Eventually, I move to just checking my watch when it’s time to start and, if necessary, giving a gentle prompt—like clearing my throat. The idea is to gradually reduce my involvement until the team naturally initiates the meeting.

Of course, I don’t remain silent throughout the daily scrum. I may prompt someone to share more details or politely interrupt when discussions veer off track, saying something like, “Maybe we should dive deeper after the daily scrum.”

To dive deeper, read “Tips for Effective and Efficient Daily Scrums.”

Mistake #3: Allowing the Team to Burn Out

The third mistake I see Scrum Masters make is that they allow teams to go beyond a sustainable pace and burn out.

I’m not a fan of much of the Scrum vocabulary but the term sprint seems especially troublesome. When I sprint while running, I tire quickly and often walk to recover.

That’s a horrible metaphor for how we’d like the team to work. Ideally, one sprint ends and the next begins. Teams shouldn’t begin their next sprint still trying to recover from their last.

“Teams shouldn’t begin their next sprint still trying to recover from their last.”

Burnout happens when teams consistently overcommit during sprint planning, usually out of an abundance of optimism about how much work they can finish during a sprint.

How to Prevent Burn Out

The first thing Scrum Masters can do to prevent team burnout is to be on the lookout for teams (and team members) who seem to be committing to more work during sprint planning than they have historically completed inside a sprint.

Another great way for a Scrum Master to guard against burnout is by talking to the product owner about giving a team time to work on things of their own choosing.

I like to do this by introducing a cycle I call 6 x 2 + 1 (“six times two plus one”).

The 6 x 2 + 1 Sprint Cycle

6 x 2 + 1 refers to six two-week sprints followed by a one-week sprint. What the team works on in the one-week sprint is entirely up to them.

“What the team works on in the one-week sprint is entirely up to them.”

Some people will use the bonus sprint for personal development (reading, video training, etc.). Others might use it to refactor some ugly code that the product owner hasn’t prioritized. (Here’s some advice on how to convince a product owner to prioritize refactoring.and how to fit refactoring into your sprints.)

Still others might try an experiment that they believe could lead to a great new feature. But it’s entirely up to the team.

Introducing a cycle like this actually benefits more than just the team. The 6 x 2 + 1 sprint cycle gives the product owner a week without any “distractions” from the team, too. (This is often the selling point that gets a product owner on board.)

This cycle can also benefit the organization if it is one that needs to make commitments like, “We’ll deliver this set of features in 3 months.” The 13th week of the 6 x 2 + 1 cycle can be used for a normal sprint if the team gets behind on a deadline. The team can then be given a week for their own work a sprint or two later after the deadline has been met.

Mistake #4: Avoiding Difficult Conversations

Scrum Masters often find themselves navigating tough conversations, from addressing recurring issues to challenging misconceptions about agile practices. Avoiding these discussions can lead to unresolved problems and low morale.

How to Gear Up for a Tough Conversation

- Embrace Discomfort: Accept that uncomfortable conversations are part of fostering a transparent, high-performing team.