A Quest For Closure: The Kansas City Firefighters Case Part 1 14 Dec 2021 8:17 AM (3 years ago)

View the movie here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZVDUVOu9dlM

The tragic case that shook Kansas City, Missouri awake over 33 years ago may now have a chance to be solved. Thanks to the Kansas City Police Department for releasing their file, new evidence has emerged. In “A Quest For Closure: The Kansas City Firefighters Case Part 1," the KCPD and federal agents had local and national media outlets implicate people in the crime without supporting evidence. The prosecution then won a conviction many are now calling into question after it was found that a key police report and crime scene photos were not handed over to the defense. In Part 2, coming out in 2022, the focus will be on how the crime was carried out according to the documented evidence and what went wrong. Visit http://kcfirefighterscase.com for more information.

The Birth of Forensic Ballistics 2 Dec 2021 3:05 PM (3 years ago)

The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in 1929 would usher in the use of forensic ballistics to solve gun crimes.

Most of us have sat mesmerized in front of a TV watching how highly motivated detectives solve a perplexing crime. The popular non-fictional series “Forensic Files” has as its mantra “no witness, no leads, no problem” which alludes to how crime scene evidence will ultimately lead to the identification of the unknown perpetrator.

Forensics, simply put, is the application of science to the law. Since the 1960s, the U.S. criminal justice system has heavily emphasized its use. A key discipline used in solving violent crimes involving firearms is forensic ballistics. Few know that the small Michigan city of St. Joseph provided critical ballistics evidence that solved one of the worst crimes of the 20th century, the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. This dark event also firmly established the field of forensic ballistics as an integral component of the legal system that is still commonly used today.

America in the Roaring Twenties was a relatively lawless land despite Prohibition. Due to the actions of social moralists and the powerful national Temperance movement, starting in 1920 there was a Constitutional ban on the production, importation, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages. While Prohibition was intended to purify society, it instead spawned widespread corruption, violence, and organized crime. It did not stop the country’s insatiable demand for alcohol. Since alcohol remained legal in neighboring Canada, enormous amounts of contraband were smuggled in via the narrow and heavily trafficked Detroit River from Windsor. Crime outfits in Chicago and Detroit massively profiteered from selling bootleg alcohol. This flourishing underground black market often led to violence between competing gangs.

The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre stemmed from who would control the highly lucrative Chicago bootleg trade. In 1928, a bitter rivalry developed pitting George “Bugs” Moran’s Irish Northsiders against Al Capone’s Italian Southside gang. Moran had started hijacking Capone’s bootleg whisky liquor shipments that were coming from Detroit. To address this, Capone allegedly sought to get Moran and his henchmen together in one location so the competition could be collectively eliminated. The crime was triggered when Moran’s gang met on a cold Saturday morning in February 1929, which coincidentally was St. Valentine’s Day.

A black Packard pulled up to the front of Moran’s garage; this was the vehicle used by the Chicago Detective Bureau. Two uniformed men entered and disarmed Moran’s men who were drinking coffee in the unheated building. After Moran’s gang was lined up along a wall other men appeared from the shadows and opened fire. Once the shooting stopped, witnesses observed that men in overcoats walked out with their hands held above their head escorted by policemen brandishing revolvers. Everyone loaded into the Packard which rapidly sped away; this seemed to implicate the Chicago Police Department.

Soon thereafter multiple police cars arrived to discover a horrific crime scene. Inside the garage, seven members and associates of Moran’s Gang were found dead along a blood spattered and heavily bullet pocked yellow brick wall. Prior to any evidence being disturbed, the Chicago coroner’s office took charge of the investigation. An array of photographs was taken that documented the crime scene followed by the systematic collection of all spent bullets, shell casings, and bullet fragments. This evidence was placed into marked envelopes that were then sealed, representing a detailed forensic chain of custody. The bullets that were subsequently removed from the victims by the coroner’s office were similarly treated and labeled with the decedent’s name.

This crime horrified the entire country and set off a public outcry demanding an end to Chicago’s rampant violence. In response, the police closed speakeasies and arrested bootleggers. Despite being under enormous pressure to solve the crime, the police quickly exhausted all their leads. The Chicago coroner’s office recommended using a new type of science called forensic ballistics to help solve this violent crime. Based on this educated gamble, they contacted Dr. Calvin Goddard, the recognized field expert to assist the investigation. To convince him to leave New York City and support the case, business leaders offered to finance a new forensic laboratory at nearby Northwestern University. This new lab was intentionally designed as a private business to exclude the notoriously corrupt Chicago police who were potentially complicit in the Massacre. The offer worked; Goddard agreed to support the case which ultimately involved his assessment of the most firearm evidence he had ever received in his career.

The new field of forensics ballistics was based on the striations (i.e., scratches) that are imprinted onto bullets fired through rifled gun barrels. It was hypothesized that these patterns were unique like a fingerprint and were traceable to a single source. Striations are due to the soft lead bullet firmly gripping the rifled gun barrel’s grooves when fired which are engineered to impart a rapid spin. This process is like the spiral pass of a football, dramatically improving the gun’s accuracy and increasing the effective firing range. The specific rifling characteristics differ between firearm manufacturers but are consistent to a particular brand, model, and caliber. If a gun was thought to have been involved in a shooting, it could be test-fired in a controlled lab setting. The resulting intact bullets are then directly compared to bullets recovered from a crime scene. This was usually done by using a magnifying glass and an investigator’s memory. If the striations patterns matched, the weapon was placed at the crime which could lead to identification of the perpetrator.

Goddard was well positioned to support the forensic assessment of the Massacre’s evidence. He had recently reviewed ballistics evidence in the Sacco and Vanzetti trial appeal that involved two immigrant anarchist bank robbers being convicted of murder. While his scientific conclusions condemned Sacco, it seemed to largely confuse the jurors and lawyers. Goddard was a World War I veteran and retired U.S. Army Colonel academically trained as a medical doctor. His intense interest in firearms caused him to leave the medical profession to focus on his avocation. Critical to his success was the invention and implementation of a new lab instrument.

In 1925, Goddard co-invented the comparison microscope which proved essential to the field of forensic ballistics becoming a recognized science by the criminal justice system. Now, instead of investigators using a magnifying glass and their recall to compare striation patterns, they could use a comparison microscope. This device is two separate microscopes side by side linked by an optical bridge. It allows an analyst to look at two different samples simultaneously and compare key characteristics. Under magnification, fired bullets mounted on a post were turned to determine if the nearly invisible striations matched. If they failed to align, then the bullets were fired from different guns. With this new technology, Goddard proved the hypothesis that no two rifled firearms are made exactly alike. Each rifled weapon made characteristic striations on a bullet that were consistent every time it was fired. Hence, a bullet taken from a murdered victim could identify the specific gun it was fired from. He also showed that striations on ejected shell casings could be traceable to a single firearm.

At the Massacre crime scene, extensive firearms evidence had been collected. This included 70 spent shell casings from the garage floor, 14 bullets that had either missed or passed through their targets and 47 bullet fragments. In addition, 39 bullets and bullet fragments had been removed from the seven murdered gangsters.

Goddard began his forensic examination by scrutinizing the spent shell casings. He quickly determined that they all were of the same make and had been fired from a .45 caliber automatic weapon. This eliminated all but two guns made in the U.S., the 45 Colt automatic pistol and the Thompson submachine gun. Close examination of the spent bullets revealed that they had been fired through a barrel manufactured with six grooves that twisted to the right. Since Colt firearms were manufactured with a left twist, this indicated to Goddard that the weapon used was the Thompson submachine gun whose barrel had a six groove, right twist. Often called the Tommy gun, in the 1920s these firearms were frequently employed by gangsters and law enforcement. Goddard’s analysis also revealed that two different Tommy guns had been used in the crime.

As Goddard labored over this firearms evidence, the citizens of Chicago demanded to know if the killers were corrupt policemen who had been feuding with the Moran gang. Under mounting public pressure, the city and suburb police submitted all their Thompson submachine guns to Goddard for forensic analysis. He systematically test-fired each weapon and directly compared the resulting bullets and shell casings to the crime scene evidence. Using his newly invented comparison microscope, Goddard firmly concluded that none of these weapons had been used in the crime which absolved the Chicago police of involvement.

Goddard’s conclusion was corroborated by witnesses who were near the Massacre site when the crime occurred. They described a tall, stocky man missing a front tooth who rapidly drove away in the alleged police car. This description did not closely match any of the city’s policemen, however, it did fit Fred R. Burke. Nicknamed “Killer,” Burke was a notorious criminal and prolific mob hitman who would do anything if the price was right. Law enforcement was well acquainted with him, especially those in Michigan. Burke had previously served time in the Jackson prison and was allegedly involved in several robberies of Detroit jewelry stores and a bank in Cadillac. He had also been associated with Capone and the Purple Gang of Detroit. He was a prime suspect in the notorious March 1927 Miraflores Massacre where three Detroit mobsters were murdered and in the killing of Thomas Bonner of Hess Lake. No one knew Burke’s whereabouts; he had disappeared from the public right after the Chicago Massacre.

This criminal investigation then went cold for nearly a year until a bizarre indent occurred 90 miles northeast of Chicago in Michigan. St. Joseph is the seat of Berrien County and was frequently visited by Capone and other gangsters. On a cold Saturday night in mid-December, 25-year-old police officer Charles Skelly was on a routine foot patrol and directing Christmas shopping traffic. He became involved in an argument involving a minor traffic accident in which local farmer George Kool claimed an unknown intoxicated man had rear-ended his vehicle. When escorting them to the police station to resolve the issue, the stranger shot Officer Skelly three times at point-blank range. While speeding away the shooter soon crashed his car on a sharp curve. Undeterred, the fugitive then stopped a passing motorist and at gun point commandeered his car to escape. When the police arrived at the accident, the driver was gone but the registration papers found in the abandoned wreck identified the owner as Frederick Dane from nearby Stevensville, Michigan. Later that night, Officer Skelly died of his wounds while on the operating table.

When Berrien County sheriffs arrived at the Dane home, Frederick was absent, and his wife did not know his whereabouts. While searching the residence, Dane’s true identity began to emerge. On the second floor of the lavishly furnished bungalow, they found a small arsenal of weapons in a locked closet. This cache included two Thompson submachine guns, around 1,000 rounds of ammunition as well as revolvers, sawed-off shotguns, hand grenades, and tear gas bombs. In addition, they found several bulletproof vests, and over $300,000 worth of bonds stolen the prior month from a Jefferson, Wisconsin bank. Laundry markings on the man’s clothing had the initials of FRB which led the police to quickly conclude that Frederick Dane was an alias for Fred R. “Killer” Burke. A latent fingerprint recovered from a household object was identified as belonging to Burke.

After contacting the Chicago police to discuss their findings, the Berrien County Sheriff’s Department sent the weapons and ammunition to the forensic lab at Northwestern University. Goddard quickly determined that most of the ammunition was of the same type used in the Massacre. He then test-fired 35 bullets from the two confiscated Thompson submachine guns. When they were directly compared to bullets recovered from the crime scene and decedents, Goddard concluded that the striation patterns matched! Both of these guns had been used to kill Moran’s men. With this data, the Chicago District Attorney’s office requested that Burke be captured and held for the grand jury on charges of murder.

The media attention surrounding this lab discovery catapulted Goddard to national fame and brought legitimacy to the fledgling science of forensic ballistics. Additional lab testing by Goddard revealed that one of the Tommy guns had also been used in the murder of New York City mob boss Frankie Yale that occurred a few months prior to the Massacre. Bullets recovered from Yale’s body were now directly linked to Burke who was the prime suspect.

Based on this cumulative evidence, Fred Burke was designated a public enemy and added to the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives. Four months later he was apprehended in Missouri based on a tip from an amateur detective who recognized him from a picture in True Detective Mysteries magazine. Instead of being extradited to Chicago, the local authorities delivered Burke back to Michigan due to the airtight case against him in the murder of Officer Skelly. This decision was also influenced by the fact that Michigan had no death penalty. Based on the preponderance of evidence, on April 27, 1931, Burke pled guilty to the second-degree murder of Officer Skelly and was sentenced to life in prison. He would fulfill his sentence at the Michigan State Penitentiary in Marquette registered under the alias of Frederick Dane. During his imprisonment he refused to implicate anyone else involved in the Massacre. Approximately nine years into his sentence, he died of a massive heart attack at the age of 47. He is buried in Marquette’s Park Cemetery under his real name, Thomas Camp.

Today, the Stevensville bungalow safe house used by Fred “Killer” Burke is still standing and the prison he resided in remains active. In addition, the Tommy guns used in the Massacre have been retained as crime evidence by the Berrien County Sheriff’s Office. They are occasionally shown at public educational exhibits. The forensic ballistics analysis of the bullet striations so important to solving this incredibly atrocious crime remains a standard investigative enquiry used in today’s crime labs. Currently, over four million digital images of striations have been incorporated into the National Integrated Ballistics Information Network, a database that catalogs firearms allegedly used in crimes. These high-resolution images are downloaded and compared to new gun evidence which has resulted in more than 200,000 hits and countless violent crimes being solved.

No More Laughs for the Fat Man: The Case of Fatty Arbuckle 24 Mar 2014 1:22 PM (11 years ago)

When Fatty Arbuckle was charged with manslaughter in the death of Virginia Rappe in 1921 he was the highest paid actor in Hollywood. The tabloid press went after him with a vengeance. Eleven years later, despite being exonerated by a jury, he died of a heart attack at age 46 as an outcast.

In today’s era of a scandal-a-day, the public furor over the case of Fatty Arbuckle and the death of Virginia Rappe seems somehow overblown and unbelievably melodramatic. The fact that Los Angeles crowds once shouted for the portly actor’s blood seems like a moralistic viciousness from a far more Puritan America. Nowadays, we’re far more cynical, and yet there’s something about the rise and fall of Fatty Arbuckle that still holds an inglorious luster.

Part of it is the age-old thrill of seeing great men brought low. The other can be located in Hollywood – a place that was synonymous with scandalous debauchery in the early 1920s. Before New York’s Daily News called him a “Beast from [sic] Gutter” in one of the paper’s typically tawdry headlines, Arbuckle (born Roscoe Conkling Arbuckle) was a rotund but agile funnyman who made silent comedy classics. A veteran of the vaudeville circuit, Arbuckle got his first break working for director Mack Sennett – the Canadian-born godfather of American slapstick comedy. Initially, Arbuckle was just another Keystone Kop working for Sennett’s Keystone Studios. Then, in the 1913 short film A Noise from the Deep, Arbuckle took the first ever pie-to-the-face. The person who threw the pie was actress Mabel Normand, a comedienne who would go on to make 17 films with Arbuckle as the beauty to his bumbling beast.

Besides Normand, Arbuckle’s other co-workers and peers included such luminaries as Charlie Chaplin (whose Little Tramp persona owed some of its success to Chaplin’s decision to wear Arbuckle’s large trousers for comedic affect) and Buster Keaton. Keaton and Arbuckle in particular became good friends and business partners, and in 1918, Arbuckle put Keaton in charge of Comique, a film company that Arbuckle had started with Joseph Schenck. Fatty transferred his share of the company because his gold lay elsewhere. In particular, in 1921, Arbuckle signed a three-year contract with Paramount. The contract paid him a million dollars per year, thus making him, for a brief time, the highest-paid player in Hollywood.

Despite his healthy bank account, Arbuckle needed a break. In his 1976 book The Day the Laughter Stopped, author David Yallop describes how Arbuckle’s schedule, which usually consisted of six films a year, some of which were shot concurrently with each other, was taking its toll on the often sickly actor. (Arbuckle’s greatest health problem stemmed from a carbuncle, which, after its lancing and painful draining, forced Arbuckle to take morphine in order to deal with the pain. In his 2013 book Room 1219: The Life of Fatty Arbuckle, The Mysterious Death of Virginia Rappe, and the Scandal That Changed Hollywood, author Greg Merritt alleges that this morphine use made Arbuckle one of Hollywood’s first drug addicts).

|

| St Francis Hotel |

The nadir of Arbuckle’s work schedule came when, right before Arbuckle’s planned vacation trip to San Francisco, the actor received agonizing burns on his buttocks. How this happened is not quite known (while Yallop claims that Arbuckle backed into a hot stove, the notoriously suspect writer and historian Andy Edmonds claims in Frame Up!: The Untold Story of Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle that the actor accidentally sat on a mechanic’s acid-soaked rag), but regardless the injury almost ended Arbuckle’s three-day vacation in San Francisco early. Eventually, Arbuckle was talked into checking in at the St. Francis Hotel by his friend and director Fred Fischbach. To sweeten the deal, Fischbach promised Arbuckle to get some illegal booze in ‘Frisco, which of course would take the actor’s mind off of his aching backside. Arbuckle agreed, and on Labor Day weekend in 1921, Arbuckle, Fischbach and the actor Lowell Sherman were the primary occupants of rooms 1219, 1220, and 1221.

Originally planned to be, in the words of Daily News writer Mara Bovsun, “an end-of-summer ‘gin-jollification,’” the party soon became a bacchanalia full of less than savory folks. Even though it occurred in the midst of that great failed experiment known as Prohibition, alcohol flowed like water at the party. Most Americans disliked the Eighteenth Amendment and its offspring the Volstead Act, so the open flaunting of illicit spirits made Fatty and company rather pedestrian. Virginia Rappe, whom history cannot confirm as either an invited guest or a party crasher, was the opposite of pedestrian, and along with her manager Al Semnancher and the shady Bambina Maude Delmont, Rappe decided to be the life of the party.

The Life of the Party

|

| Virginia Rappe |

Rappe was originally born a “Rapp,” but added an “e” on her surname because she claimed it sounded “more elegant.” It was all for naught, for Virginia’s unfortunate last name eerily presaged the grand accusation at the center of Fatty Arbuckle’s railroading. Like Arbuckle, whose own childhood was a maze of torment and abuse, Rappe’s early life can be summed up in one word: “tragic.” The illegitimate daughter of Mabel Rapp, Rappe was primarily raised by her grandmother after her mother’s death. As Rappe grew into her raven-haired good looks, she also grew up too fast and began engaging in a lifestyle that would ultimately lead to her death.

Before and during the trial, journalists of the yellow variety did their best to depict Arbuckle as an overweight beast – a latter day Bluebeard with a Kansas-sized paunch. In many ways, the newspapers took over where Arbuckle’s father had left off, and like the comedian’s old man (the party responsible for naming Fatty after his least favorite politician, the Republican party boss Roscoe Conkling) the newspapers of the 1920s did their best to demean and demoralize the once beloved screen idol. As part of this organized character assassination, the newspapers did their best to uphold Rappe as a virtuous and wholly innocent victim of Arbuckle’s deranged lust. She was the white virgin to Arbuckle’s black beast, and her dramatic death seemed perfect for self-righteous pearl-clutching.

In truth, Rappe was anything but virginal. Rappe was raised without a father figure in the bustling metropolis of New York, and as a result she pursued numerous sexual relationships at a tender age and without an awareness regarding sexual contraception. As a result, Rappe suffered from bouts of venereal disease, plus it was rumored that she had had several abortions before the age of 16. At the age of 17, Rappe became the mother of an out-of-wedlock child in the tradition of her own mother.

None of this seemed to drastically affect Rappe’s career; however, and by the time of the party at the St. Francis Hotel, Rappe was a bit-part actress and a relatively well-known artist’s model who had graced the cover to the sheet music for “Let Me Call You Sweetheart.” Rappe was also engaged to one Henry "Pathé" Lehrman, one of Sennett’s men and an occasional director of Fatty Arbuckle shorts. Lehrman’s working relationship with Arbuckle didn’t mean that the two were close. In fact, Lehrman and Arbuckle were known to have a long-running feud, and Rappe wasn’t above joining in. In “Fatty Arbuckle and the Death of Virginia Rappe,” Crime Library contributor Denise Noe claims that at one point Rappe called Arbuckle “disgusting and crude...vulgar and disrespectful to women.” While these words would come to haunt Arbuckle during three different trials, Noe sees them as the platitudes of Lehrman’s loyal lover.

Arbuckle’s opinions of Rappe are a little less known to history. Some sources claim that Arbuckle was smitten with the attractive actress, while others insist that Arbuckle didn’t care for either Rappe or her set. Furthermore, on September 5, 1921, Arbuckle didn’t want either Rappe or her friends drinking all of his liquor. By all accounts that’s exactly what they did, and after several hours of imbibing, Arbuckle found a naked Rappe screaming in his room.

Arbuckle claimed during his testimony that he, Delmont, and other guests initially placed Rappe in a tub full of ice. Next, the group called for the hotel doctor, who injected Rappe with a shot of morphine. In the morning, Rappe’s condition only continued to deteriorate, and finally, after three days of agony, Rappe was taken to a nearby hospital. On the fourth day, Rappe was taken to the Wakefield Sanitarium, an institution widely known for performing abortions. Finally, on Friday, five days after the party, Rappe died of peritonitis caused by a ruptured bladder.

Almost immediately, Delmont cried “murder.” According to her, during the early stages of the party, Arbuckle had grabbed Rappe and dragged her against her will into his bedroom. Delmont told the police that Arbuckle said: “I’ve wanted you for five years” just before closing the door. After a quarter of an hour, Delmont said that Arbuckle had reappeared as a sweaty, exhausted-looking man. Rappe had remained behind on the bed and told Delmont that: “I’m dying. He did it, Maude.”

From her vantage point, Arbuckle had raped the girl, and furthermore, the actor’s great weight had crushed her, thus causing her bladder to rupture. Years later, smut junkies like Kenneth Anger would claim that Arbuckle had penetrated Rappe with either a Coca-Cola or Champaign bottle, but at the time of the actor’s ordeal, Delmont’s nebulous accusation of rape was enough to effectively end Arbuckle’s career.

Even before he went to trial, Arbuckle was found guilty in the press. Unfortunately for him, Arbuckle’s case occurred during the height of the tabloid era and the birth of so-called Jazz Age journalism. Ever since June 26, 1919, when the Daily News debuted the tabloid format, American newspapers had given in to printing lurid and sensational headlines that came packaged with plenty of pictures. Arbuckle’s fame, his girth, and his profession all made him a perfect fall-guy for the media’s obsession with Hollywood’s moral rot.

On top of this, the death of Virginia Rappe was just another shocking case from the film world. Earlier, in 1920, the actress Olive Thomas had died after drinking a lethal quantity of mercury bichloride. The chemical compound belonged to her husband Jack Pickford, a handsome screen idol whose short life was ruled by scandal, drink, and drug abuse. Rumors had it that Pickford used the mercury bichloride to treat his syphilis, plus even more wagging tongues proclaimed Thomas’s death an act of suicide. Even though it was eventually ruled an accidental death, much of the American public believed Hollywood to be viper pit controlled by immorality.

Arbuckle’s trial, plus the concurrent scandal of the still unsolved murder of William Desmond Taylor, put Hollywood squarely in the sights of moral crusaders. William H. Hays, a former chairman of the Republican National Committee and the one-time Postmaster General, was eventually called in to be Hollywood’s in-house policeman and censorship board, and on April 18, 1922, Hays banned Arbuckle from making any more films. Although the ban was lifted in December 1922, the damage to Arbuckle’s career was irreversible.

The sad thing here was that Hays’s ban had been enacted on an innocent man. After three trials, which lasted from November 1921 until March 1922, Arbuckle was finally acquitted on all charges. In the first trial, Arbuckle was charged with manslaughter, but after giving convincing testimony on the stand, Arbuckle and his defense lawyer netted a hung jury, with 10 to two in favor of not guilty.

During the second trial, Arbuckle did not take the stand. Coupled with a generally poor defense, Arbuckle’s silence caused yet another hung jury, this time 10 to two in favor of conviction. During the third and final trial, Arbuckle once again took the stand, and after the prosecution’s star witness (Zey Prevon, a showgirl and model) was charged with perjury, the jury only took minutes to reach a decision of not guilty. Most of the jury’s time spent deliberating was actually put towards drafting an apology letter to Arbuckle, which the jury foreman read aloud:

Acquittal is not enough for Roscoe Arbuckle. We feel that a great injustice has been done him. We feel also that it was only our plain duty to give him this exoneration, under the evidence, for there was not the slightest proof adduced to connect him in any way with the commission of a. He was manly throughout the case and told a straightforward story on the witness stand, which we all believed. The happening at the hotel was an unfortunate affair for which Arbuckle, so the evidence shows, was in no way responsible. We wish him success and hope that the American people will take the judgment of 14 men and woman who have sat listening for 31 days to evidence, that Arbuckle is entirely innocent and free from all blame.

Despite his exoneration, Arbuckle was forever tainted as some kind of monster. During the trials, his films were banned across the country, while constant newspaper coverage did untold damage to his character and his reputation. But while Arbuckle’s life was being ruined, the newspapers were having a field day. William Randolph Hearst, the man in charge of the San Francisco Examiner and one of America’s first media moguls, once boasted that the Arbuckle case sold more newspapers than the sinking of the Lusitania.

Because of this undue media attention, the Arbuckle case attracted more than just readers. Various con artists and hucksters, along with the professionally outraged, all gained some notoriety because of the Arbuckle case. Delmont for a short time became a public speaker and a crusader against the social excesses of Hollywood, but her second career was cut short after it was revealed that her previous job included blackmail and extortion. In particular, Delmont was known to set-up famous people for the purposes of blackmail, and she may very well have intended for Rappe, a heavy drinker with a penchant for taking off her clothes while drunk, to seduce Arbuckle during the party.

Other colorful characters in the case included Lehrman, who used the case as a way to further his career, Semnacher, a small-time hood who changed his testimony halfway through the case, Gavin McNab, Arbuckle’s San Francisco defense attorney who later represented heavyweight boxer Jack Dempsey, Milton U’ren, the Assistant D.A. who was so dedicated to convicting Arbuckle that he charged Prevon with perjury after she refused to say that Rappe had incriminated Arbuckle in her presence, and a little known Pinkerton detective named Sam Hammett.

Other colorful characters in the case included Lehrman, who used the case as a way to further his career, Semnacher, a small-time hood who changed his testimony halfway through the case, Gavin McNab, Arbuckle’s San Francisco defense attorney who later represented heavyweight boxer Jack Dempsey, Milton U’ren, the Assistant D.A. who was so dedicated to convicting Arbuckle that he charged Prevon with perjury after she refused to say that Rappe had incriminated Arbuckle in her presence, and a little known Pinkerton detective named Sam Hammett.

Before he took to calling himself “Dashiell,” Sam Hammett was a private detective in San Francisco with a serious case of tuberculosis. Despite his rapidly declining health, Hammett was hired as one of Arbuckle’s guards throughout the trials. Although the experience was only a small part of Hammett’s career as a detective, it nevertheless made an impression on the budding writer. On the one hand, Hammett claimed that: “The whole thing [the Arbuckle case] was a frame-up...arranged by some of the corrupt newspaper boys,” while on the other he openly loathed the portly star. In fact, writers such as the novelist Ace Atkins and the scholar Dr. William Marling have often claimed that Hammett used Arbuckle as the model for his obese villains such as Casper Gutman in The Maltese Falcon.

By the time that The Maltese Falcon was published in 1930, Fatty Arbuckle was no longer “Fatty Arbuckle.” Working under the pseudonym William Goodrich, Arbuckle spent the early ‘30s as a director of short comedies. Then, in 1932, Arbuckle signed a contract with Warner Bros. to star in a handful of two-reel comedies as “Fatty Arbuckle.” Although these six films were successful in America, the long shadow of Virginia Rappe’s death continued to haunt the actor, and when trying to show the film Hey, Pop! in the United Kingdom, the British Board of Film Censors cited the 1921 scandal as a reason for refusal.

On June 29, 1933, Arbuckle died of a heart attack at age 46. The once adored comedy star ended his life as an outcast: An innocent man suffering because of an unscrupulous media and an occupation’s bad reputation. Even though his nimble exploits and comedic timing make him the forefather of John Belushi and Chris Farley, Arbuckle will forever be associated with a three-day party in San Francisco. This is probably the greatest crime of all.

A Blonde in Babylon: The Death of Thelma Todd 10 Feb 2014 1:00 PM (11 years ago)

Screen star Thelma Todd’s untimely death in 1935 set off wild speculation about the cause of her demise. Was she murdered or was she the unfortunate victim of carbon monoxide poisoning?

Hollywood has always been about making grand illusions. The movies are where people go for escape, high adventure, or just a chance to glimpse a world we wish existed. There’s a lot of gold in mythmaking, and Tinseltown has always been known for its bright, shiny, and extravagant character.

It sounds cliché to say it, but nonetheless true—the Land of Make Believe can and is often full of nightmares. With every star that climbed his or her way up the ladder to international fame and fortune, there are thousands of waiters and waitresses who never quite made it. Some went back home to Iowa or Oklahoma, while others started searching for rock bottom in a bottle or in a needle.

And of course “making it” is no guarantee for the good life either. Tabloids exist to pick through the wreckage of famous and fabulous lives, and the fact one can still find plenty of them in the checkout aisle speaks volumes about the decadence that still exists in Southern California. This is essentially distilled noir, and like the movies themselves, noir has a uniquely American flavor—a rich and sweet form of corruption that attracts the eye as much as it repels the soul.

|

| Thelma Todd |

In the early 1930s, some Americans caught wind of this and tried to change which the way the wind was blowing. Although a lot of the Hollywood gliterrati viewed them as yokel bums, the followers of William Harrison Hays Sr. had a proud lineage that stretched across the centuries. Their progenitors were the Puritans, then they spent time crusading underneath the banner of Progressivism. What they wanted was “good government”—a squeaky clean idea that sought the end of corruption, filth, and exploitation. They also wanted control, especially control over the media. The movies in particular were sought because they had so much power. Hays and his mostly Midwestern do-gooders knew that life could easily imitate art, and what they saw on the screen shocked them.

Before the coming of the so-called Hays Code, which tried to censor films based on a set moral order, Hollywood was rife with perversion. On the screen, characters dabbled in drugs and women showed too much skin. There was even more space allotted for violence, and movies such as The Public Enemy and Little Caesar spun stylish tales about the era’s favorite character—the Tommy Gun gangster. When the Presbyterian elder and former U.S. Postmaster General Hays was finally allowed to put into practice the Motion Picture Production Code, he helped to authorize a binding list of “Dont’s” and even more “Be Carefuls.” Under “Dont’s,” things such as “White slavery” or “Sex hygiene and venereal diseases” were completely off limits for any motion picture, along with “The illegal traffic in drugs,” “Ridicule of the clergy,” or “Any licentious or suggestive nudity...” In the “Be Careful” category, the Hays Code suggested avoiding “Brutality and possible gruesomeness,” “Sympathy for criminals,” and so-called “First-night scenes.” The Motion Picture Production Code effectively tried to clean up the pictures, and the impact was immediate. In 1931, three years before the enforcement of the Hays Code, James Cagney was allowed to smash a grapefruit into Mae Clarke’s mug in The Public Enemy. By 1934, the biggest scandal of the year was Clark Gable’s lack of an undershirt in It Happened One Night.

Away from screen, the stories that would get out about the Hollywood lifestyle made the movies themselves seem tame by comparison. Like the shindigs at Gatsby’s Long Island mansion, the Hollywood of the 1920s and early 1930s looked like one big riot, and like all Bacchants, sometimes these party animals became real wolves. Fatty Arbuckle got caught with a girl and Coke bottle, while the It girl, Clara Bow, supposedly slept her way through the USC football team. Most of these accusations are probably false, but Hollywood is a place that thrives on made-up truths, half-truths, and no truths.

Thelma Todd, a beautiful blonde originally from the harsh Massachusetts textile town of Lawrence, became another victim of the Hollywood plague in 1935. And like the other tragic stars before her, Todd’s death (and now afterlife) is a cause célèbre of the morbidly inclined.

In life, Todd was far from the world’s most popular glamor girl. Getting her start during the silent era, Todd capitalized on her good looks (which earned this former schoolteacher a job in Hollywood in the first place) in tons of comedies and a few dramas. Like her likeness Jean Harlow, Todd captured the screen as a light-hearted heartbreaker, and re-watching films like Horse Feathers, which starred all four of the Marx Brothers (Groucho, Harpo, Chico, and Zippo), validates that concept.

Although a Chicago Tribune writer called Todd “a cross between Goldie Hawn and Farah Fawcett” back in 1991, the real Thelma Todd was far more troubled than her latter day imitations. This vivacious comedienne ran with a pretty mean set, from a washed-up director to a wife beater who may or may not have been muscle for Charles “Lucky” Luciano. The washed-up director in question was Roland West—a man who was best known for his silent horror and mystery films that starred such luminaries as Lon Chaney Sr. and Boston Blackie himself, Chester Morris. By 1930, West was fresh from yet another triumph. This time around his victory was called The Bat Whispers, and this update on the 1920 Avery Hopwood play would eventually go on to influence a young Bob Kane, who would use the film’s arch-criminal, known as The Bat, as one of the templates for his own vigilante known as Batman. In that same year, a married West began a personal and financial relationship with Todd after a fortuitous trip to Catalina Island.

Before long, Todd and West were partners operating a restaurant called Thelma Todd’s Sidewalk Café. The café quickly became the place to seen, and tragically, Todd was last seen alive not far from the eatery that bore her name.

Her final resting place was her car—a 1932 Lincoln Phaeton. Slumped over and disheveled despite wearing what Los Angeles Times writer Robert W. Welkos describes as “a mauve and silver evening gown, expensive mink wrap and adorned with a small fortune in jewelry.” Todd was dressed for a party and on the night of her death, Todd and her friends were toasting her until the wee hours at the Trocadero on Sunset Boulevard.

Police Photo

At 3:15 a.m. on Sunday, December 15, 1935, Todd was dropped off at the café. She did a little walking, and crime scene photos show that her heels bore the trademark scuffs of an uphill trudge. The next morning, the police found Todd’s body and were soon going through every nook and cranny in order to determine a cause of death.

Unlike a lot of fabled Hollywood mysteries, Todd’s death seems pretty cut and dry. The coroner found a significant amount of carbon monoxide in her blood, thus making carbon monoxide poisoning the likely culprit responsible for Todd’s long goodbye. When she was discovered, the ignition in her car had been left on but the engine had died with a little gas left in the tank. According to British journalist Christopher Snowden, Thelma, “cold and unable to get into her apartment at the locked Café, trudged up to her car in the garage, started it up and turned on the heater.” Before long, the odorless carbon monoxide overwhelmed her and swallowed her up.

This end is decidedly unglamorous and does not mesh well with Todd’s larger-than-life persona. Because of this, wagging tongues immediately began offering alternative conclusions, and these unfounded theories have done plenty of damage to the image of “Hot Toddy.”

First of all, it was widely disseminated that Todd’s body was bruised and battered, thus hinting at murder. The people who believe this pointed to West (a man rumored to have a hot temper and a jealous streak), Jewel Carmen, a former prostitute, silent film actress, and West’s protective wife, and Pasquale “Pat” DiCicco, Todd’s shady ex-husband.

While those in favor of West’s guilt blame Todd’s death on the director’s covetousness, those in favor of Carmen’s articulate an idea that Carmen’s illegal gambling operations and other illicit activities were somehow threatened by Todd. For these people, the whole circus around Thelma Todd’s Sidewalk Café is comparable to the Bada Bing! In “The Sopranos.” Gambling upstairs and a protection racket run by Lucky himself, this version of café seems like a murder plot waiting to happen. Some have even speculated that Luciano himself ordered the hit, but as with most things surrounding Thelma Todd’s death, there’s a paucity of evidence to support this claim. But hey, it’s a good story!

The underworld connection is further highlighted in the figure of DiCicco, an ex-pimp and bootlegger who was a fixture among the nightlife set in Los Angeles. Because of his last name and reputation, many amateur and armchair detectives have labeled DiCicco a lieutenant in the employ of Luciano. Again, there's little support for this claim.

Still, despite this lack of credible evidence, DiCicco remains a highly alluring figure—almost as if Central Casting found him and made him out to be the perfect murderer. On the night of Todd’s death, eyewitnesses claimed that DiCicco and Todd got into a heated argument. Not long after, DiCicco hotfooted it to New York, and when the grand jury summoned him to testify back in California, DiCicco claimed that he hadn’t heard about his ex-wife’s death (Todd and DiCicco were married from 1932 until 1934).

Later, in 1941, DiCicco married the 17-year-old heiress Gloria Vanderbilt. According to Vanderbilt’s autobiographical writings, DiCicco was a brute who liked booze too much, which gave him a loose hand and an even looser temper. Whether or not DiCicco treated Todd in a similar fashion, is a question up for debate.

All things considered, what seems not up for question is the reason for Todd’s death. Despite West’s deathbed confession and despite the various letters from cranks, it seems fairly certain that Todd died an accidental death. The problem of course is that Todd’s prosaic ending is full of colorful elements and people. From the death and extortion threats that Todd received earlier in 1935 (which have never been argued away and even formed the source material for a newspaper article in March of 1935) to Andy Edmonds’ sensational book Hot Toddy (which is full of so many factual errors that it only muddies the waters further), the produced and sold mystery around Todd’s death just will not die. And even today, there are people who will tell you that Todd is still around, haunting the former hot spots of Hollywood and Los Angeles like the sad and unavenged ghost of some low-budget horror flick.

The Murder of the Black Dahlia: The Ultimate Cold Case 3 Feb 2014 11:33 AM (11 years ago)

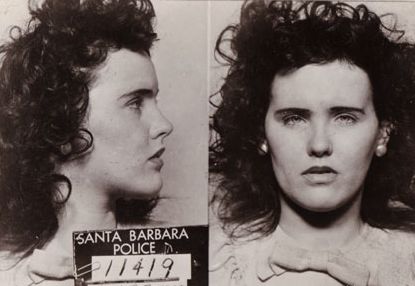

When the severed, mutilated corpse of Elizabeth Short was discovered in a vacant lot in Los Angeles on January 15, 1947, the search for the murderer of the “Black Dahlia” began its futile run. Over the intervening decades many theories have been advanced about who this killer was, but none have given serious consideration that he was a jilted boyfriend who stalked her as she emerged into the night from the Biltmore Hotel.

In crime lore, the murder of Elizabeth Short, a/k/a the “Black Dahlia,” has achieved iconic status. Speculating on the murder of the Black Dahlia has turned into a cottage industry, with books and movies advancing a wide array of perpetrators. The truth is it remains the ultimate cold case, but there is the possibility she was murdered by an enraged, jealous boyfriend who stalked her from San Diego to the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles.

The enigma of Elizabeth Short and her brutal mutilation-murder brings two very

different pictures to mind. The first is a photograph of a vibrant and vivacious young

woman, very beautiful and self-possessed. The second is a horrible image of a defiled and besieged corpse, lying naked, drained of blood, and severed in two on a weed-infested vacant lot on Norton Avenue in Leimert Park, Los Angeles on the morning of January 15, 1947.

The gruesome discovery sent shock waves across the country. About a day and a half later the dead woman was identified by fingerprints. When news broke of the name of the 22-year-old victim a few people came forward to Los Angeles police to say they knew her. Police quickly established the last sighting of Elizabeth Short as being the night of January 9, at the time she left the Biltmore Hotel.

The medical examiner surmised from the extent of bruising spread over a wide area of her corpse that she had been severely beaten. There was no evidence of sexual assault because the killer had washed and scrubbed the body clean.

John Gilmore in Severed: The True Story of the Black Dahlia and the anonymous author of Infamous Murders – published by Chartwell Books in 1989 – report that the homicide bureau speculated Short had been tied up spread-eagled, either in a standing or supine position or suspended head first by a makeshift system of ropes and pulleys. That she was kept bound in this position for the period of her internment, as in a coarse and crude bondage session. The tell-tale signs being ligature marks at the wrists and ankles and impressions made by rope knots indented on the front, back and left side of her neck. The cause of death was listed as blunt-force trauma to the head. Numerous cuts had been inflicted by a sharp-bladed instrument in a criss-cross pattern over her pubic area, and pubic hair was torn out by hand. A knife was used to cut open her cheeks from each corner of her mouth, leaving a gaping injury from ear to ear. She was then cut in half at the waist and her body drained of blood.

No one knows the complete picture of her suffering.

The ‘Black Dahlia” Myth is Born

Overnight Short was dubbed “The Black Dahlia” by a sensation-seeking press. Kenneth Anger in Hollywood Babylon II and Steve Hodel in Black Dahlia Avenger suggest that reporters en masse, in their efforts to learn more of Short’s movements and lifestyle, talked to acquaintances already referring to her with this term.

When Elizabeth Short first arrived in Los Angeles she lived in Long Beach and frequented a drug store. She wore her hair dyed black and outfitted herself in black garments. She was possessed of a fair complexion and striking, classic looks and the contrast of dark and light accentuated her beauty.

The drug store owner, Arnold Landers, told reporters that customers had already begun calling her the “Black Dahlia.” A “B” movie, The Blue Dahlia, had opened about 10 days earlier at a nearby theater with Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake playing the lead roles. Lake was a voluptuous golden-blonde and patrons of Lander’s shop who became friendly with Elizabeth Short began referring to her as “The Black Dahlia.” When newspapers across the United States began splashing this moniker on their front pages, Elizabeth Short was on her way to an ironic form of immortality.

Elizabeth Short in Hollywood and San Diego

In the late 1940s, Hollywood resonated images of sunshine and prosperity. With the dark days of war over and the passage of time, a new era dawned. The motion picture industry pulsated. Thousands of people across the vast expanse were beckoned. Elizabeth Short would be one of these, arriving by train at Union Station in Los Angeles in July, 1946. Like in Nathanael West’s The Day of the Locust, as a newcomer to town, she quickly gravitated to strangers and odd individuals of like-mind for support and company.

According to www.theblackdahliainhollywood.com, Short’s stay in Los Angeles had been a hit-and-miss affair. In four and a-half months she had lived in nine locations, moving eight times. Her first residence was at the Washington Apartments in Long Beach in late July. From there she rendezvoused with Gordon Fickling, an ex-U.S. Air Force pilot she had known from back east. They moved in to the Brevoort Apartments on Lexington near Vine Street in Hollywood, but separated soon afterwards. Short then contacted Marjorie Graham, a girlfriend from Boston living in Hollywood and the two women roomed together, sometimes with a third person, at five different locations from late August until October 22, when Marjorie returned to Massachusetts. Their temporary residences included the Hawthorne Apartments in Hollywood, later the Figueroa Hotel in downtown, the private home of Florentine Gardens Nightclub owner Mark Hansen, and the Guardian Arms Apartments, also in Hollywood.

Short’s last residence in Los Angeles was a small and cramped apartment at the Chancellor in Hollywood, where she bedded down with seven other women in one main room, consisting of double-bunk beds alongside each of the four walls. A corridor separated this room from a narrow kitchen at the other end of the apartment, with a bathroom in between, off the small corridor.

On December 8 she took the Greyhound bus south to San Diego. Later that day she fell asleep in the Aztec Picture Theater and was awakened by Dorothy French, a 21-year-old cashier and usherette. Short spent a month living with Dorothy, her mother Elvira, and younger brother Cory in their home in Pacific Beach, just north of the city limits. During this time she dated a number of men, one of whom was Robert “Red” Manley, a 26-year-old travelling salesman from Huntington Park, in Los Angeles. On January 9, 1947 it would be Robert Manley who would drive Elizabeth Short back to Los Angeles and let her off at the Biltmore Hotel.

Short was discovered dead the following Wednesday, January 15. Betty Bersinger, a local resident, was out walking hand-in-hand with her 3-year-old daughter along Norton Avenue, when she came upon the shockingly mutilated remains of a young woman. She gasped in horror as she halted, frozen in fear. Then upon regaining her composure collected the child in her arms and ran to the nearest house, and immediately raised the alarm.

The press and police rapidly descended and soon a crowd of onlookers swarmed, agog to the stark sight that met their gaze. The chilly winter added an eerie and uneasy feeling. The gruesome spectacle that winter’s morning was one that was to go down as America’s most infamous cold-case murder mystery of the 20th century. What people set their eyes upon that day was the body of a young woman severed completely in half at the waist. The two sections lying slightly at diagonals of each other were drained entirely of blood and grotesquely mutilated.

The Killer Calls the Editor

On the afternoon of Thursday, January 23, 1947, J.H. Richardson, the editor of the Los Angeles Herald Examiner, received a brief telephone call from a man who alluded to himself as the killer. The caller promised to mail Richardson some of Short’s belongings as proof of his claim. (Richardson later in For the Life of Me: Memoirs of a City Editor recounted his conversation with the supposed killer. He perceived the man to be an egomaniac, a “superman” as Richardson worded it, who wanted to show the world what he could do and get away with it. This claim by Richardson was never made public at the time.)

Two days later, the only genuine item of mailed correspondence known to have come from the killer was intercepted by a sharp-eyed employee at the U.S. Postal Service on January 25, 1947.

Letters cut from the pages of a daily newspaper were pasted to the front of an envelope which read, “Los Angeles Examiner and other Los Angeles Papers. Here! Is Dahlia’s Belongings, Letter to Follow.” The small packet-sized envelope measured 8 inches by 5 inches. It was carefully and delicately pried open by the police.

Pacios in Childhood Shadows- The Hidden Story of the Black Dahlia Murder’ itemizes the contents of the packet as a Greyhound claim-check; Short’s birth certificate; a Western-Union telegram signed “Red”; some snapshots; an assortment of business cards; a hand-sized, leather-bound address-book with the name “Mark Hansen” embossed in gold lettering on the front cover; and newspaper clippings of Mat Gordon’s obituary. Hodel in Black Dahlia Avenger: A Genius for Murder writes that the envelope was dropped into a public mailbox at a downtown Los Angeles location and franked January 24, 1947 6:30 p.m.

The same day the envelope was posted the black handbag Elizabeth Short was carrying and the black suede high-heeled shoes she had been wearing at the Biltmore were recovered from the Los Angeles dump. Robert Hymans, who operated a cafe at 1136 South Crenshaw Boulevard, a few blocks from the death site, had noticed the shoes jutting out from the handbag where they had been tossed atop a garbage can, then driven away by the garbage truck. The killer had obviously mailed the contents of the handbag as he had told editor Richardson he would then dumped the handbag and shoes.

The small packet-sized envelope seized by police reeked of gasoline, causing detectives to surmise that the killer had momentarily toyed with the idea of burning the envelope, then decided to mail it after all. Other law enforcement reasoned the shrewd culprit soaked the packet to remove fingerprints.

Fingerprints however were enhanced by the LAPD crime-laboratory and despatched forthwith to the FBI for cross-matching, but no match was retrieved from existing files. The public has never been privy to whether the prints were complete and intact or partial, hazy smudges. But with no match on file in 1947, the Los Angeles Homicide Bureau concluded the perpetrator had never, up until murdering Elizabeth Short, been arrested for a crime and had never been fingerprinted and that the crime was a one-off aberration.

As decades passed with still no match forthcoming, detectives further deduced that the person responsible never again fell foul of the law.

A Special Grand Jury Convenes

Despite all the years having elapsed since the discovery of the murder of Elizabeth Short, the LAPD “Black Dahlia” files are still closed to the public. The files are contained in four filing-cabinet drawers. Only one LAPD homicide detective, aptly referred to as the “gatekeeper,” has the exclusive access to these drawers until the privilege is passed on to the next gatekeeper. This secrecy over the files is now obsolete. Almost every person associated with Elizabeth Short has died. Short herself would have turned 90 years old on July 29, 2014.

In early 1949, the office of the L.A. District Attorney empanelled 12 civilians to form a special grand jury to investigate police corruption throughout the ranks of the LAPD. The other prime-purpose was to look-into the failure of the LAPD to solve the “Black Dahlia” murder and a string of other brutal slayings and abductions of women across the same time period. This monumental undertaking lasted the entire year.

The grand jury findings brought to light an avalanche of corruption at the highest levels. Inter-departmental jealousies and secrecy prevailed and were wide-ranging and it was found that very often information was not passed on. These revelations led to a complete shake-up of the LAPD, throughout the ranks.

Although many positive actions came in terms of bleeding out any festering corruption within the LAPD, there was little forward movement in solving the murder of the “Black Dahlia.” One result of the grand jury’s deliberations was to cull the list of 22 suspects the D.A. investigators identified as possible suspects to a handful for follow-up investigation.

Profiling the Killer

Two theories prevail about the “Black Dahlia” homicide. One was that Short had never met her killer and the other that she knew him. What supports the second view are the mutilations inflicted on her corpse. To some investigators they are signs of a personal vendetta. Renowned FBI criminal profiler and author John Douglas adheres to this theory.

Douglas formed the view that the killer knew the victim well and held an emotional attachment toward her. He sees the killer as someone who lived alone, had a high school education, engaged in manual labor, and was under great personal and financial strain at the time of committing the murder. Douglas also suggests the murderer was not averse to wallowing in blood and could have worked as a butcher or in a similar profession or perhaps was a person who was accustomed to hunting animals and was likely as a child or youth to have mistreated or abused animals. The killer Douglas believes may also have been burdened by a personal physical defect or disability.

To Douglas, the ferocity and violence perpetrated on Elizabeth Short, the horrific mutilations to her corpse and the disposing of her severed body on public land for passerbys to discover are all telltale signs the killer knew the victim. The message being conveyed is that this was personal and based on a perceived wrongdoing the killer believed Short had done to him.

This personal association or perceived emotional closeness the killer felt he had to Short, coupled with individual criteria known about each suspect can be used as a premise to eliminate suspects from the DA’s 22 suspect list. From this list there were only seven suspects who were proved to have known Short on a social or personal level.

The D.A.’s Short List of Suspects

Of the seven suspects, only one deserves special mention. George Bacos, head usher at NBC Studios at Sunset and Vine in Hollywood, was an ambitious 23-year-old who was employed on a commission basis at a record promotion company, Jay Faber Associates. As another sideline to an already busy schedule, Bacos contracted entertainment talent to nightspots around town, including the Crown Grill located two blocks south of the Biltmore Hotel. Short frequented this establishment and was last seen walking in this direction.

Bacos had met Short while dating Short’s roommate, Lynn Martin. During the four plus months Short lived in Los Angeles, Bacos took Short out 12 times. When Short was identified as the murdered woman, police sought Bacos for questioning. His statements to police contained comments that were both disingenuous and derogatory towards his slain acquaintance. Website www.theblackdahliainhollywood.com provides the following quotes, attributed to him:

"I used to see her with a lot of people. As a matter of fact, for my part I tried to avoid her as much as possible. I was new in radio and made contacts, and she dressed kinda cheaply, you know too obvious and everything... I didn’t want to kiss her because of all that goop she used on her face. I’m used to nice cultured girls."

Photographs of Short taken in Los Angeles during the second-half of 1946 convey a strikingly attractive young woman who was discerning and elegant in the manner she dressed. Her blouses were buttoned to the neckline. There was nothing cheap or revealing. In fact she dressed with a taste for quality, contemporary fashion and outfitted herself in classic black. Her favourite colors were pink and blue.

Bacos says he was used to “nice cultured girls” yet he confessed to dating and having had sexual relations with Lynn Martin who was found to be 15 years old. She had lived with Short and Marjorie Graham at several hotel apartments in Hollywood and downtown. She essentially lived off the generosity of boyfriends and associates and from casual employment. Young women living on the fringes were easy targets for men of means like Bacos.

Jack Egger was head-usher at CBS Studios at Columbia Square on Sunset Boulevard near Gower Street. He liaised with Bacos on a professional level. Egger said of Bacos, to DA investigators, “I don’t like him very well. He is very conceited; I just don’t care for him myself. Never very close to him, just speaking acquaintance.” Egger related that Bacos frequented Brittingham’s Restaurant and Cocktail Bar adjacent to the CBS building. Bacos told investigators in response, “That used to be my hangout. I’d see her in there. I’d say hello, be as nice as possible, try to get away.” Remember this is what Bacos said after Elizabeth Short was found, the victim of a brutal mutilation-murder – a person he had dated a dozen times.

Bacos went on to become a television-writer in the 1960s and 70s. He received critical acclaim for writing a three-episode segment of the “Kojak” television series named “Night of the Piraeus.’ At age 80 in 2003 he wrote the novel Warriors Down. The setting is the backdrop of the Vietnam War with guerrilla fighting and news-reporting rampant. The lead character is a Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist Michael Traynor. Traynor’s forte at journalism is brilliant and raw but far too honest and clean for some in the U.S. government – too close to the brutal truth. Those in positions of high office wanted his reporting contained. Feeling ostracised, alone and betrayed Traynor, now diminished, holds three criteria close to his heart which are worth living for: They are to reclaim his good name and self-respect and last in capital-letters REVENGE.

It is strange and uncanny that Bacos writes a novel late in life that has revenge as its principal theme. Revenge is destructive and insidious and at odds with reclaiming self-respect and one’s good name. Short’s murder is believed by many to be a crime based on incredible anger stemming from revenge.

Both the LAPD and the DA investigation held him to be a good suspect. There was no direct evidence but it is interesting that nearly three years following Short’s murder the DA had him on their condensed list of 22 suspects, aligning themselves with the LAPD. Bacos is a definite possibility.

Debunking the Black Dahlia Literature

There have been several film adaptations and a number of books written recounting the murder of Elizabeth Short.

James Ellroy’s “The Black Dahlia,” a superbly drafted work of fiction, was published in 1987. Its main thrust was not so much about the murder and Elizabeth Short herself, but about the people around her and those investigating her murder, who become obsessed with Short and what happened to her. This is a theme that continues to the present day. There has been a number of non-fiction books authored afterwards and released onto the market.

Severed - The True Story of the Black Dahlia by John Gilmore is original, daring and masterfully written, depicting late 1940’s shadow-land noir Los Angeles. He builds his case outlaying the known facts with an interconnecting series of cameos or fabled stories coloring the pages. Jack Anderson Wilson is identified as the killer, a petty criminal harboring a long rap sheet, which lists burglary, theft and violence as his mainstay code of offenses. Despite continuing decades of similar activity intermingled with prison time, Wilson restricted his bad deeds never graduating to harder crime.

Severed was the first non-fiction work to be written and when released went down as a resounding success and was triumphantly acclaimed. For example Kenneth Anger is quoted as saying “My God, this is a frightening tale....The most famous murder in L.A., and we suddenly see that we knew nothing before, only the glitter and red of blood. This, now, is Pandora’s Box.” Charles Higham was quoted as saying “This project stands as the only authentic true-crime book written on America’s most bizarre and haunting murder case.” But in the years since its release in 1994 there have been many detractors.

Gilmore did not provide any footnotes or endnotes, nor an index or bibliography. There is no way to clarify a lot of the things he has written. People have tried. One is Los Angeles Times journalist Larry Harnisch, who in 1997 wrote a story for the Times on the eve of the 50th anniversary of the “Black Dahlia” murder. Harnisch who did his own research then and in the years since is quoted as saying that Gilmore’s book is 25 percent mistakes and 50 percent fiction. Gilmore expounds a number of cameos within the pages of Severed. Harnisch has said he has never been able to establish the existence of any of these characters Gilmore wrote about.

There is no evidence whatsoever Elizabeth Short ever met or knew Jack Anderson Wilson. None of her associates in Los Angeles ever mentioned him. Neither the Los Angeles Police at the time or the DA investigators mention him or held him to be a suspect.

One of the main selling points of his book was his theory that Short had infantile genitalia and was incapable of having intercourse and was a pseudo-hermaphrodite. This has, since the release of Gilmore’s book been disproven. Detective Harry Hansen and the LAPD found three people who had sexual relations with Short. The coroner’s autopsy report states that Short’s reproductive organs and system were “anatomically normal.”

Until Gilmore wrote his book there was little research or interest on the “Black Dahlia” murder but its releasesparked a renewed popularity and devotees and researchers have since taken him to account. John Gilmore is without doubt a highly talented writer and Severed is spellbinding and chilling, but the pages are cluttered with fairy tales.

Janice Knowlton in Daddy was the Black Dahlia Killer asserts that her father George Knowlton impregnated Short in November 1946 and because of this pregnancy murdered her. Don Wolf in The Black Dahlia Files reports that newspaper mogul Norman Chandler, owner of the Los Angeles Times impregnated Short after she had serviced Chandler as a call girl through notorious madam Brenda Allen, and that gangster Bugsy Siegel murdered her on Chandler’s orders and that Gilmore’s suspect Wilson was an accomplice. These claims make great fiction but are preposterous. The autopsy report confirms Short was not pregnant.

Both Knowlton in Daddy was the Black Dahlia Killer and Wolfe in The Black Dahlia Files assert that Short was a prostitute. Knowlton even claims that Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Short worked together as a double act. These claims are totally refuted by the DA investigation and by the Los Angeles police. Detective Harry Hansen in charge of the murder investigation stated “there was no record of any solicitation, offering or resorting or prostitution in any way, shape or form. She was no pushover. She’d bait and take all she could get and give out nothing. She did not put out.”

Steve Hodel in Black Dahlia Avenger: A Genius for Murder nominates his own father George Hill Hodel as the killer. Dr. Hodel was a very distinguished medical practitioner and highly regarded. But his reputation was totally destroyed when in 1949 his teenage daughter Tamar Hodel accused her father of incest and threw in for good measure a statement naming him as the “Black Dahlia” killer. Following the fallout from these allegations and his trial, even though he was acquitted of the incest charge, his reputation in tatters, he left Los Angeles early the following year, 1950. He was thoroughly investigated by the Los Angeles police and by the District Attorney’s office. Both agencies came to the conclusion that he had nothing to do with Short’s murder. One blundering Hodel makes within his 500-plus pages is to tell readers that two photographs displayed in clear black and white are of Elizabeth Short. Neither bust-shot looks anything like her. Hodel was forced to retract a few years back now when one of the women still alive came forward to say she was one of the young women and that she was a friend of the late Dr. George Hodel.

William T. Rasmussen’s Corroborating Evidence: The Black Dahlia Murder is a thoroughly documented and very informative work. The author makes the case linking the “Black Dahlia” murder to the “Cleveland Torso” murders of 1934-38. But along with Don Wolfe’s Black Dahlia Files he jumps on the bandwagon and backs Gilmore’s suspect Jack Anderson Wilson as the serial killer. There is no evidence of Wilson’s involvement in either case. No evidence he was even a killer at all.

Childhood Shadows: The Hidden Story of the Black Dahlia Murder was written by Mary Pacios, a childhood friend of Elizabeth Short from Boston. A very definitive and well written look at Short’s life prior to her arrival in California, her book provides an invaluable insight into the real person and the private world of Short. Pacios, incredibly, names wonder-boy Orson Wells, the actor and director and star of Citizen Kane, as the killer.

The Curse of the Black Dahlia by Jacque Daniel details the involvement of her father J. Paul de River, the police psychiatrist overseeing the case. Leslie Dillon was 27 and working at a hotel in Miami when in October 1948 he wrote a letter to De River after reading an edition of True Detective magazine which detailed the crime along with a psychological profile of the killer.

An exchange of correspondence ensued with the psychiatrist concluding Dillon was the murderer. A trap was set with the purpose of extracting a confession, culminating with Dillon being held against his will at a hotel near Los Angeles, without counsel, his constitutional rights being denied.

Because of this unlawful detention, a writ of habeas corpus was issued and Dillon had to be released. The fiasco led to the convening of the 1949 grand jury and the dismissal of Police Chief Clemence Horrall, following the investigation of police corruption within the LAPD.

Nonetheless, after a comprehensive investigation with evidence presented, the grand jury named Leslie Dillon as the prime suspect. Although Dillon was never indicted, there are strong reasons suggesting he should have been.

Fred Witman, a colleague of Dr. de River, was sworn in to give testimony in September 1949 before Deputy District Attorney Arthur L. Veitch and Chief H.L. Stanley of the Bureau of Investigation.

Witman divulged that subsequent to the murder he had called Dr. de River having reached two conclusions. Firstly he believed the killer had worked as an embalmer at an undertaking firm, and secondly, based on his personal expertise of such crimes and of the individuals who commit them, predicted the murderer would, by his own doing reveal himself to authorities at some point.

If Dillon were the killer then Witman was correct on both counts. Dillon had worked in Oklahoma City and in Oakland, California as an embalmer's assistant and ended up writing to Dr. de River in October 1948, thus exposing himself.

Witman further produced in testimony a photograph taken by the medical examiner of the slashed pubic region of Short's corpse and pointed out that the letter "D"' had been carved into her flesh. Deputy District Attorney Veitch then asked Witman "There is also apparentlly an 'E' or an 'F' there" to which Mr. Stanley of the Bureau stated "Definite 'E' ."

The carving of these two letters into the flesh of Elizabeth Short is a revelation in itself. There is no mention of this in the official coroner's report and the LAPD has always denied the existence of any initials carved on the deceased.

Author Jacque Daniel herself states that she and a colleague had viewed the photograph in the DA files and states in her book "and there was no initial 'D' that we could see."

But if one examines the photograph of the pubic region closely the letter "D"' can be seen in the outer-upper right-side of the pubic region and what appears to be the letter 'F' alongside to the right, although if the authorities were correct in 1947, and they most probably were then it is an"'E".

Witman alluded that Dillon was always in the habit of signing pictures he drew, simply with the letter "D". The carving of the two intitials must be part of the information pertaining to the'Black Dahlia case that has always been held back by police even to the present day.

There is no mention of it in any books or articles and it was omitted from the autopsy report and its existence emphatically denied by the LAPD. But anyone can see the initals if they look closely. This photograph is in Severed by John Gilmore, for all to see, though Gilmore never mentions it.

The police and DA failed to established Dillon's whereabouts after January 8 until January 16, 1947. He was working in San Francisco until January 8 and from January 16. There was a mountain of circumstantial evidence pinning him to the murder, but he was not brought to trial for two reasons. Firstly because he had been illegally detained and secondly for a lack of concrete evidence. Apparently he had a witness or witnesses who were willing to come forward, in the event he was put on trial, to say he was in San Francisco at the time. The police believed these characters were unsavory and lacked credibility.

The downside to the book is the author's misguided attempt to implicate people in high places and unnecessarily delve into tangents of conspiracy theories. Regardless, it is the opinion of the author of this article that Daniel's book is the most credible and compelling. The question begs to be asked: Did Leslie Dillon murder Elizabeth Short?

One fact not mentioned in Daniel's book is worth noting. The handbag and shoes belonging to Elizabeth Short were left atop a trash can at 1136 S. Crenshaw Boulevard on January 24th, 1947, nine days following the murder. This was most probably the killer's only mistake. But it was a colossal blunder on his part. The killer did not foresee the possibility that someone might link the items to the murder. It was a mistake because it reveals that the murderer most probably lived within walking distance. This was an astounding oversight by police at the time.

Dillon lived at 906 S. Crenshaw Boulevard in 1946, two blocks away. He was living in San Francisco in January 1947 but returned to live in Los Angeles in April 1947. It is possible Dillon kept the rent going for the South Crenshaw address, knowing he might return. If he rendezvoused with Elizabeth Short or met her for the first time after she had alighted from the Biltmore Hotel via the Olive Street exit then she was killed at 906 S. Crenshaw Boulevard. This address has never been proposed as the place of her execution.

Over the years several films detailing the “Black Dahlia” homicide have come to the screen. The Blue Gardenia, a 1953 Warner Brothers picture, was the first loosely based adaptation. “Who is the Black Dahlia,” a 1975 made-for-television movie was next starring Lucy Arnaz and Efrem Zimbalist Jr. In 1981 True Confessions followed, starring Robert DeNiro and Robert Duvall. Finally 2007 saw the release of The Black Dahlia, based on the 1987 book by James Ellroy.

An Alternative Scenario

There is an alternate scenario never put forward in any books or movies that may explain what happened to Elizabeth Short: She was being stalked by a jealous boyfriend she went out with in San Diego. Of major support to the stalking theory is that no one in Los Angeles knew when Short would return. In fact, after a month in the San Diego area, she even came back a day later than she had planned to.

When Manley gave his statement to homicide detectives following the murder, he revealed a peculiar anomaly that interrupted the drive. He noticed Short craning and twisting her head round to the left as cars were passing in the same direction, and back toward those vehicles travelling south in the opposite direction. The logical explanation for this odd manifestation was that she was concerned someone she knew might be following her. Call it intuition or premonition, but it is not an uncommon occurrence for intensely appealing women to be stalked and this might have happened to her in the past.

Manley also told detectives he had noticed scratch marks on the outside of Short’s upper arms and a trickling of fresh blood. He said Short had told him she had a very jealous boyfriend who was of Italian descent. But the jealous Italian boyfriend she referred to could only have been one person, Sam Navarra.

From the police investigation of her time in San Diego, a day-to-day time-table of Short’s movements established who she had been out with and how she filled in her time during that month. Website www.blackdahlia.info outlays this timetable. The only man of Italian descent was Sam Navarra. Short had stepped out with Navarra on the last night she spent at the home of Elvira and Dorothy French at Pacific Beach, January 7, 1947. When LAPD detectives interviewed Navarra he told them that Short had said she was leaving the next morning to return to Massachusetts.

Manley arrived outside the French’s Pacific Beach home the next morning, January 8, and following an exchange of farewells the two were under way. But instead of heading off to a bus station for Short’s announced trip back to Massachusetts, they drove only a few miles before pulling in at the Mecca Motel where they booked a cabin for that night. Manley, working as a travelling salesman, had calls to make the following morning and Short made a decision to bide her time and wait until the next day January 9.