How Mario Napoli Beat Chen Village Taiji 15 Dec 2016 9:58 AM (8 years ago)

Excerpted from Mario Napoli’s interview at Taiji Forum.

I was in a no man’s land concerning this art. I just could not get it! I was lost, demoralized and had [already] quit Tai Chi Chuan [once]. I only went back to it because I heard how good [Stanley Israel] was… so I figured I’d give Tai Chi Chuan one last try.

We hit it off instantly. After just touching him, I knew he was the one who was going to teach me. He made it sound, look and feel so easy. It was very refreshing and I felt as if I understood everything he said explained and showed! He made it fun for me to go to class. The work was hard, but I took to it like fish to water.

“Just push!”

We had many debates and Stan would always say to me, “Why are you so confused?”

It began after a pushing [hands] lesson when he said to me “Mario, just push.” and I would say, “What do you mean, just push? I mean I can push this way or that way…” Then he would repeat “Just push,” and I would again say, “But I may just end up shoving! Shoving is wrong, right?”

“Right! Shoving is not good but…Just push.”

I would reply. “As you can see I can’t push correctly…it’s not my fault… I’m doing my best… people are telling me this and that, or I’m doing it all wrong. Understand?”

I would say, “Are you telling me, it’s OK to be wrong?” Then he said, “All I’m telling you to do is just push!”

After many months of this back and forth, we ended up striking a bargain. I would do whatever I thought he meant, to the best of my ability; and if I was wrong he shouldn’t take it as a lack of trust on my part, or that I didn’t listen or didn’t care. And it was his responsibility to correct me and not assume the worst.

I was to abandon all thoughts of what was right or wrong and “just push,” whatever it meant to me that day! I no longer held any baggage of what “pushing the Tai Chi Chuan way” meant.

Hard work

After I began to do OK with this push hands thing, [Stanley Israel] used to make me do free-style push hands with a row of people. My job was to stay in the ring and play with as many people as possible. One day I did the whole row, without losing once! There were about 15 people.

So what did I do when that happened? I sat down, naturally! I was satisfied that I’d beat them all without losing. He walked over to me and said, “What are you doing?” Self-satisfied, I answered him. “I did them all Stan, so now I’m just chilling.”

He said, “Did you lose?” I said “Hell no! I wouldn’t be sitting if that happened! I beat them all,” and then jokingly, “I’m the king of the hill!”

[Stanley] said, “Okay kid, do it again, and see how long you last this time around.” So I went back and did some more.

After I’d beat maybe 7 or 8 people, I sat down again and was now really tired. Stan once again came over…

“Should you not try and finish the line?”

Chen village competition

I initially saw a video of the competition in Chenjiagou and I said to myself, I can take these guys…

Someone [named] Mike Sigman, a self-proclaimed Tai Chi expert, actually dared me to go and find out for myself how great these Chen folks were! (Actually, Mike was telling everybody that he was going to go and give it a try himself, but backed out at the last minute.)

Truth be told I never trained specifically for the Chen Village competition. We always trained hard on our own; it was our way. We had a small but dedicated group, and many people would come around to practice with us: wrestlers, judo players, Taijiquan teachers and such.

Our game was simple: we did freestyle push hands in a circle. Throw the guy down or out of the circle and you’ve won…that’s it! Pulls, trips, throws, body shots and such were allowed. Punches and kicks were not allowed.

If you won, you’d stay on the mat. Lose and you’re off the mat. We would train 3 times a week for about 3 hours a session.

As for the tournament itself, while I did enjoy it, and it was head and shoulders above any other tournament that I’d previously seen…it was still nothing special. When a guy with only one good knee, suffering from dysentery and not eating any food for 4 days, wins the whole thing, [that] should tell you something.

I beat Wang Zhan-jun and Wang Zhanhai, who were All-China National Push Hands champions. I beat the first one in the finals; the other one forfeited the match, saying that he was in no shape to play me.

In the main I was treated well afterwards, with most of the people there seeming to like the fact that I won. However, it was all made clear when the Chen officials went out of their way to put me down. Instead of being smart and saying yes, everybody has a chance of winning, they choose the lower road. I guess they felt really bad that a foreigner, sick and all, showed them how it should be done.

The post How Mario Napoli Beat Chen Village Taiji appeared first on Martial Development.

Charles Manson and the Many Faces of Tai Chi 3 Dec 2016 1:41 AM (8 years ago)

Writer and Tai Chi expert Scott Meredith recently made this keen observation about Tai Chi marketing:

This graphic shows the unconscious cultural bias that affects internal training. What do all these have in common? Yeah – they show only upper body, arm gestures, or at least massively emphasize the upper body, arms, hands and heads, to the partial or complete exclusion of feet, legs, and hips…

Our profound entrancement with the upper body has made us all tense as hell up there. That’s one issue. The other issue is that, paradoxical as it may seem, the only way to get the real internal in the upper body (arms, hands, whatever) is by relentless internal conditioning of the lower body (feet, legs, hips).

All of that is true. Modern humans really are obsessed with their upper bodies. Our middle and upper class jobs are performed with hands and eyes, while the lower body is resting in a seated position. And even after forty to fifty hours of office work, leading to pathologically tight hip flexors and hamstrings, most of us would still prefer to skip leg day at the gym.

Lower body workouts are a tough sell. I myself have accidentally frightened away new students in the past, by demonstrating a low posture in an introductory Tai Chi class. As Scott implied, Westerners have been conditioned to expect a vibrant new level of health, as a result of adopting exotic Asian hand positions. To be confronted with the coarse reality of a low squat is a deeply dissonant experience.

Marketing professionals and cover designers know this, and respond to the desires of the marketplace.

It’s fun to make cynical observations about advertising. Nevertheless, let’s acknowledge that martial artists and marketers have a common goal: influencing others’ behavior with minimal cost and effort. Tai Chi fans ought to learn from the wisdom displayed by these ad packages. It’s not about excluding the waist and everything below. It’s about focusing on a human face.

Human beings are genetically predisposed to pay attention to faces. It is an essential practice for survival, friendship and cooperation. We use faces to communicate our inner emotional state, and to read the moods of others.

Faces convey emotion, and emotions sell products. This is why so many of them with no particular relevance to the human body, are nevertheless advertised alongside smiling faces. Or, in the case of the Tai Chi instructional products shown above, a contented and relaxed facial expression.

Violence, like shopping, is a deeply emotional performance. We use our faces to incite, threaten, accept, escalate, decline, and end acts of violence. In fact, this form of body language communication is so effective that it often precludes any need for overt physical force. We establish dominant and submissive roles quickly through posture and expression alone.

Manipulative facial expressions are core tools for sociopaths and for certain high-level politicians. Charles Manson is a prime example. After using his talents to establish a personality cult, he subsequently convinced them to murder on his behalf. Later convicted for conspiracy, Manson lost his freedom and his flock, but he never lost his contempt for common social norms and those who follow them. See this remarkable 1989 interview with news anchor Penny Daniels:

What does any of this have to do with the art of Tai Chi Chuan? That depends on your personal definition of the art. Many people today regard it as an ancient Chinese health dance, great for decreasing stress and removing toxins and such. When analyzed at that level, any discussion of violent sociopaths is distasteful and irrelevant.

If on the other hand we define Taijiquan as a style of martial arts, or unarmed self-defense…subtle facial expressions are still not important. In this case, we assume the inevitability of the fight, along with the need to quickly end it. From this point of view, we are less interested in analyzing faces, and more in rearranging them: with a fist, or on the ground.

However, if we look at Tai Chi in a broader sense, as an art of keeping and taking balance, faces become extremely important. Far more so than any arm postures or horse stances. In my experience, one well-timed glance is enough to end a fight, and one poorly chosen smirk is enough to guarantee one.

According to rumor, Charles Manson enjoyed playing a version of tuishou with his cult family. He would quickly and unpredictably change his facial expression, and challenge others nearby to match him. Like other influential sociopaths, he understood that, long before we might push anyone with our arms, we have already touched them with our face.

The post Charles Manson and the Many Faces of Tai Chi appeared first on Martial Development.

Karate Kata Secrets of the NBA 1 Nov 2016 10:34 PM (8 years ago)

First and foremost, a master of Karate must become a master of the obvious. While mid-level belts are distracted by the novelty of obscure or secret kata applications, the expert must constantly return to his or her fundamentals.

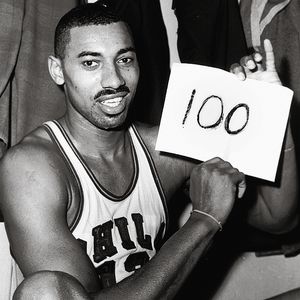

Wilt Chamberlain is an intriguing example of this approach. Decades after his retirement from the NBA, he still dominates the record books. Wilt took the most shots, and scored the most points of any player in the league. (He was also very successful on the basketball court.)

Yes, Wilt Chamberlain was clearly a gifted athlete; but there is another important contributing factor to his success. Did you know he used a free throw kata?

It’s true. Not only that, but he remained loyal to this practice, despite clear evidence that his kata did not work.

There is a lesson here for every teacher and student of Karate. It’s a lesson about deep fundamentals.

First, though, let’s review the story of Wilt Chamberlain’s free throw kata, as told by Malcolm Gladwell on This American Life:

For sheer physical presence, there has probably never been anyone like Wilt. There are lots of seven footers who play basketball, who are basically on the court purely because they’re seven feet tall. They’re clumsy and ungainly.

Chamberlain was not like that. He was as big as an oak tree and as graceful as a ballet dancer. That season, 1961 to 1962, he ended up averaging more than 50 points a game. That record will never be broken…

March 2nd, Wilt was hungover. He’d been out all night with a woman he picked up at a bar. That’s classic Wilt, too.

He would later claim to have slept with 20,000 women in his life. And when he said that, lots of people did the math and said, there was no way that was possible, given the fact that there are only 24 hours in a day, and Wilt only lived to the age of 63. But even the skeptics were like, well, maybe it’s 10,000 or 8,000. It was an argument over whether it was an unbelievably high number, or merely an incredibly high number.

So back to the game in question. Chamberlain makes his first five shots and has 23 points at the end of the first quarter. At halftime, he has 41 points. No one’s thinking history just yet. But then, by the end of the third quarter, he has 69 points. And he keeps going and going and going….

100 points, the most anyone has ever scored in a professional basketball game. And here is the most incredible thing about it– he shot brilliantly from the foul line, made 87.5% of his shots. The reason that’s incredible is that Chamberlain was a horrendous free throw shooter, the worst.

He was a man who could score at will with two and sometimes three defenders draped all over his body. But put him all alone, 15 feet from the basket, and he was hopeless. There were seasons in his career where he shot 40% from the free throw line. That’s terrible.

But this season, Chamberlain changes tactics. He starts to shoot his foul shots underhanded. He doesn’t release the ball up by his forehead. He holds the ball between his knees and flicks it towards the basket from a slight crouch. Some people call that a granny shot. And all of a sudden, he’s a pretty good free throw shooter.

He makes 28 free throws, the most anyone has ever made in a regular season game in NBA history. He made 28 out of 30.

Take a moment here to imagine yourself in Wilt Chamberlain’s giant shoes.

Imagine you are the highest scorer in NBA history. Imagine you’ve just learned how to increase your free throw percentage from a miserable 40 percent, to nearly 90% success–just by replacing one basic sequence of movement (kata) with another. What are you going to do next?

Well, here is what Chamberlain actually did:

Wilt Chamberlain stops shooting underhanded. And what happens? He goes back to being a terrible foul shooter.

Let’s think about what he did for a moment. Chamberlain had a problem. He tested out a possible solution.

The solution worked. And all of a sudden, he’s fixed his biggest weakness as a player. This is not a trivial matter.

If you’re a basketball player and you can’t hit your free throws, you’re an incredible liability to your team, particularly at the end of close games. The other side simply fouls you every time you touch the ball because they know you’ll miss your free throw and they’ll get the ball back. If you can’t hit your foul shots, it means you can’t be used in a tight game.

You know what Chamberlain’s coach said to him about his free throws? “If you were a 90% shooter, we might never lose.”

Chamberlain had every incentive in the world to keep shooting free throws underhanded, and he didn’t.

In his autobiography…Chamberlain wrote– “I felt silly, like a sissy, shooting underhanded. I know I was wrong. I know some of the best foul shooters in history shot that way. Even now, the best one in the NBA, Rick Barry, shoots underhanded. I just couldn’t do it.”

Malcolm Gladwell believes this is a story about irrationality, peer pressure versus perfectionism, and the Threshold Model of Collective Behavior. Go ahead and listen to the entire podcast. He is a convincing storyteller.

Malcolm Gladwell thinks this is a story about how to shoot free throws, but he is wrong. He is overlooking fundamentals. This is a story about why to shoot free throws.

Chamberlain returned to his overhand free throw kata, even as he knew that by doing so, he would lose points for himself and for his team. Why? Because he wanted to look manly. Which is a completely rational decision, for someone who enjoys sleeping with 2 or 3 different women every day of the week, and prioritizes that above certain aspects of his basketball game.

All of this applies to your own Karate practice. Consider the sequence of movements in Heian Shodan, for example…

- Do you know how to turn and block? Yes, of course you do…but do you really?

- Why should a downward block be followed by a step and a punch? If that combination doesn’t work in sparring practice, should you keep doing it anyway?

- What is your motivation for punching and kicking in uniform? Which fundamental human needs does it satisfy?

- In your Karate practice, do you prefer to be “rational,” or “manly”? And what precisely is the difference?

Add your own kata questions, answers and secrets below.

The post Karate Kata Secrets of the NBA appeared first on Martial Development.

Empty Your Cup, Part Deux 30 Oct 2016 1:48 AM (8 years ago)

“Empty your cup,” the master said. “Your cup is overflowing.”

“Maybe stop pouring then?” I replied.

“It’s a metaphor,” he snapped. But it was too late anyway. My loafers were ruined.

“Now clean up that mess,” he ordered with a stern look. ”And brew another pot!” I quietly walked back to the kitchen. This was not how I pictured my blissful weeklong vacation at an authentic Zen monastery.

Through the kitchen window, I watched the staff. They were on break again. Sitting outside, smoking cigarettes, and watching soap operas on a portable television. I could not imagine why a small mountain temple needed three employees in the kitchen, but I knew better than to ask. Just another ancient mystery to contemplate, as I prepared a fresh pot of Oolong.

Ten minutes later, the tea was ready. For the seventh time that afternoon, I filled the Zen master’s teapot. I rinsed the ceremonial cup, and placed it on the ceremonial tray, following his instructions precisely.

As I carried the tea set back to the old monk, I gazed at the faded murals in the hallway. A travel brochure had claimed they were historical record. To me, the number of dragons seemed rather suspicious.

Even as I contemplated those figures on the wall, I realized they were only a distraction from my assigned task. Or perhaps the task itself was a distraction? I continued walking. Does anyone really need eight pots of tea in a day?

I entered the great meditation hall once again, approaching the old monk on his pillow. Suddenly my wet loafers slipped on the stone floor. The ceremonial tea set flew from my hands, and shattered into a hundred pieces.

I was not particularly bothered. Calmly, I picked myself up off the ground, while the monk sat expressionless ten feet away. We watched the liquid flow into a puddle, between the stones and shards.

I stomped on the puddle until it disappeared. Tea service was over.

“It’s a metaphor,” I explained.

As I turned to leave the monastery, the old monk raised his arm. He gazed for a moment at the fresh mess in the hall. Then he smiled and stated simply: “No refunds.”

Image credit: Wikimol

The post Empty Your Cup, Part Deux appeared first on Martial Development.

The Automotive Applications of Tai Chi Chuan 21 Oct 2016 10:54 PM (8 years ago)

Over the past few months, I have made a careful survey of Seattle’s Tai Chi skills. I have toured the community centers, local parks, and martial arts studios. Watched many classes, spoken to dedicated and passionate instructors. After reviewing these groups, I can tell you exactly where to find the best Tai Chi in Seattle.

Go to the northeast end of downtown at rush hour. Or try just south of Montlake cut. You can also head west from Green Lake. Yes, if you really want to see the best Tai Chi applications in town, just find any steep hill with a stoplight.

For any readers living on the flat Midwestern plains, I’ll give a quick lesson on two-footed driving in Seattle. To start safely on a hill, keep your left foot on the brake pedal, while gently increasing pressure on the gas. Once the car has started pulling forward, release the brake.

Very simple, with an automatic transmission. Any teenager can learn this with a few hours of repetition, feedback, and refinement.

Indeed, all over the city, you’ll find experienced drivers using this technique to navigate stop-and-go traffic, in darkness and rain, without accident. It’s unremarkable, really…unless, as a martial arts enthusiast, you consider one terrifying alternative…

Imagine that same teenage driver next to you. Imagine that, rather than applying this standard pedal technique, they are instead relying upon those common “principles of Tai Chi.”

Are you afraid? If not, you should be. Picture yourself idling on a steep hill, trapped behind a driver who believes that, in order to move forwards, one must first move backwards!

Can you imagine that driver slowly releasing their brake, then pausing for a deep relaxing breath, before reaching for their gas pedal? Get your insurance card ready, because that crazy person is going to hit you.

These are not really Taiji principles, of course. They are a pervasive “Tai Chi” fantasy, supported by the misinterpretation of opaque and ancient text.

Fortunately, in the real world today, almost nobody operates a car in such a foolish manner. We know that our gas and brake pedals are distinct mechanical linkages (or electronic sensors), rather than abstract cosmic opposites. We know that we need to adjust our timing and pressure on the pedals, in order to match the incline of the hill and the proximity of other cars.

Other details are less obvious, but still relevant. The depth of our brake pads and tire tread, the octane rating of our gasoline, the effects of recent weather, and so on. All of these details color our interaction with the pedals; consequently, with other cars and their drivers. Truly, everything matters, even the floor mats.

We cannot learn to drive by reading classical poetry. The task is complex, and our language is limited. Most of our useful learning is done on the road. Similarly, the real principles of Tai Chi Chuan reveal themselves in conscious directed practice. The old masters’ text must reconcile with our lived experience, and vice versa; otherwise, the art is truly dead and gone.

Our human bodies are far more complex, and more important to us than any automobile. I believe that Taijiquan is a great vehicle for understanding ourselves, our posture and movement, and the relationships we create thusly. But we cannot stop our self-examination at the level of pan-Asian bromides and vague invocations of “relax and turn the waist.”

We should not, in the pursuit of distant and esoteric ideals, overlook the near and plain lessons in our lives; such as, how to drive safely on a wet Seattle road. Because if we do that, it will forever remain easier to find Tai Chi applications outside of class than inside it.

Chris Marshall is an eminent martial arts writer, and the instructor at Shoreline Tai Chi. He currently teaches in the Seattle area.

The post The Automotive Applications of Tai Chi Chuan appeared first on Martial Development.

Unlocking the Warrior Spirit: Duckling Edition 28 Apr 2011 5:30 AM (13 years ago)

It’s not the size of the duck in the fight, but the size of the fight in the duck that counts.

The post Unlocking the Warrior Spirit: Duckling Edition appeared first on Martial Development.

From Homeless to World Champion: The Story of Kickboxer Marco Sies 19 Apr 2011 3:35 AM (13 years ago)

Excerpted from The Master Method: Four Steps to Success, Prosperity and Inner Peace by Master Marco Sies

Growing up, I experienced difficulties and personal conflict that I’ve worked very hard to overcome. Some of these struggles stemmed from negative influences and people who told me I wasn’t good enough…I was inferior…I wasn’t smart…I was too poor, too small, too unattractive to make anything of myself. I was told so many negative things so often, I actually spent many years believing these things were true.

Very small for my age, I was a dark-skinned boy living n a not-yet diversified [Chilean] population where light skin was admired and favored. At school, little girls told me I was ugly, and the boys bullied me relentlessly. I remember being thrown headfirst into a trashcan, and the humiliation of a group of boys whipping me with their neckties and making me run like a horse while they laughed. Even some of my relatives made hurtful comments…

Some of those negative childhood experiences stayed with me well into adulthood. I now understand that these experiences were necessary to help me identify what I didn’t want for myself…

By the age of five or six, I already had a fascination with kickboxing, persistently pleading with my dad to show me moves and “train” me. Although I wanted to be a great fighter, no one took this undersized boy seriously, and especially one who had his head buried in philosophy books most of the time.

A New Determination

When I was 15, an exhibition by world champion kickboxer Bill “Superfoot” Wallace in my hometown changed the course of my life. I was awed by his power, mastery and discipline, and I decided that very night I wanted to become a world champion. I would train and learn and work harder than anyone ever had and let nothing stop me from reaching my goal. When I shared my thoughts with others, they scoffed and laughed at me, but once my decision was made, I began to make my plan.

I began working every job I could find to earn even the smallest amount of money [for training]. I washed dishes, helped people carry groceries to their cards, I swept floors, and I even walked several miles to and from school so I could save my bus money. I was determined to accomplish my goal, and I knew this was going to help me get closer to it. Small opportunities began to fall into my path, and eventually, I was able to find work at a martial arts school cleaning floors, bathrooms and mirrors. I never looked at these duties as beneath me, but rather as an opportunity.

This first martial arts job allowed me to train and improve my martial arts and kickboxing skills, and after a couple of years of relentless, grueling work, I proudly became the Chilean National Champion. I was only eighteen years old, and it was an enormous achievement. I maintained my title fro the next three years, but my eyes were still on the world title…I knew I had to go to Europe or the United States.

Coming to America

I arrived in America with $40, a couple pairs of pants and shirts, some music tapes and my martial arts uniforms. I settled into an ambitious routine, working as a cleaner late at night, delivering newspapers in the early morning hours and still training at every opportunity.

We would often drive all night to get to an event and then go straight to the weigh-in. I would fight and we would drive straight back home because hotel accommodations weren’t in the budget.

The world of kickboxing is a tough business, with purses going mostly to the promoters and the actual fighter taking the physical punishment for only $200 or $300. In those early years, I met people who promised me training, fights and other “deals,” but I didn’t understand anything about contracts, and was so green I assumed no one would be unethical or have bad intentions.

At one point, I was convinced to travel to California with the promise of big money for just a couple of fights. I spent two months there and never got paid a dime. I returned to the East with nothing–no job, no money and no place to live.

At this low point, I found myself homeless, and I didn’t know where my next meal would come from.

Despite these major setbacks I never lost faith. I was so focused on becoming a world champion…without knowing why, I was accepting everything I experienced as part of my journey. In hindsight, I realize each trial gave me the knowledge and tools I need to become a kickboxing world champion.

Within a few months I was back on my feet, and even though I had to work even hard to sustain myself, I didn’t worry. I couldn’t afford a boxing gym, but I found an old couch near a dumpster, took the cushions off, tied them to a tree, and that became my punching bag. I trained in the parking garage at a local mall, running up and down the stairs, and I ran sprints in a local park. I used all the creative means I could think of to continue my training every single day in hot sun, rain or snow…

Continued in The Master Method: Four Steps to Success, Prosperity and Inner Peace by Marco Sies.

The post From Homeless to World Champion: The Story of Kickboxer Marco Sies appeared first on Martial Development.

Are Action Movies Ruining Martial Arts? 12 Apr 2011 5:00 AM (13 years ago)

In New York Magazine, Kyle Buchanan laments the decline of the modern action movie:

…Actors often brag about how much Krav Maga or karate or capoeira they had to learn for their roles, but to judge from the onscreen world of modern action movies, that kind of skill set is hardly rare: A built-in understanding of martial arts is instilled in everyone, be they hero, villain, or mere henchman. (Fortunately, heroes always get to fight off bad guys who somehow know the exact same form of martial arts they do.) Too often, it seems like movies grind to a halt for obligatory hand-to-hand combat with low stakes and little invention, as though the screenwriter typed, “A fight breaks out,” and the director left it up to the second unit and fight coordinator to fill three minutes.

With little in the way of stakes, a sameness in presentation, and no blood or bruises, martial arts have turned action scenes into dance scenes…Gone are the days when a fight might involve a gun, a makeshift weapon, or a hit that actually hurts.

Mr. Buchanan misremembers the history of violence in cinema.

Before The Matrix ignited our current wuxia craze, with its improbable spinning kicks and high-precision fisticuffs, how did our heroes show their combat prowess? Primarily, as I recall, with a bullet-deflecting aura, flawless aim, and a bottomless clip.

In other words, these earlier fights were conducted with magical talismans, and not any representative of actual firearms. Imagine Harry Potter with a five o’clock shadow, versus an army of cross-eyed dragons that can’t shoot straight. In whose eyes were these gun battles any more realistic, or exciting, than (even formulaic and poorly choreographed) hand-to-hand combat? Within which paradigm it easiest for us to suspend disbelief, or to empathize?

America has always been uncomfortable with self-cultivation myths. The power of the cowboy, our original American superhero, flowed through his sidearm–and we are apparently meant to imagine he cast it himself, along with all the ammunition; but in contrast to legendary Eastern kung fu masters, our storied independence was always a product of the general store.

Superstar Jackie Chan, for example, is a real-life product of long and bitter kung fu training, and in the films that built his career, many of his characters share a similar background. Whereas, when courting an American audience, his movie plots too often concern a cybernetic tuxedo, or a magical medallion. (If you’ve seen either of these, then you know that twice is already too often.)

Fortunately for martial arts fans, not all on-screen violence is mediated by technology. While today’s hand-to-hand combat can be frantic, yet implausibly sterile, some scenes from decades past are unintentionally hilarious. Star Trek is a prime example, illustrating that there never was a greatest generation, or a golden age for violent action.

So what are the crucial truths about fighting and martial arts that popular movies obscure? First, that there is any difference at all between fighting and martial arts. Second, that there is a difference between fighting for dominance, and fighting for survival; even when lives are at stake, action movie heroes are more concerned with displays of personal heroism (no surprise here), and less with pragmatism or efficiency. Third, that a “successful” overt action is, at best, a rectification of previous failures at covert influence…

How are martial arts and the entertainment industry influencing each other? Is either improving, or corrupting the other? What do you think?

The post Are Action Movies Ruining Martial Arts? appeared first on Martial Development.

The Best of Karate Kyle Contest 8 Apr 2011 10:13 PM (13 years ago)

The Contest

I need you to help Karate Kyle express his seething rage. First, decide what he needs to say. Second, jump over to quickmeme.com and type in your idea–you’ll receive a captioned image immediately. Finally, save it, and leave a link to your original creation in a comment below.

Submissions will be accepted until April 8; then voting begins. Three winners will receive fun custom bobbleheads from 1minime.com:

- Winner #1: Readers’ favorite submission (with 10 or more votes)

- Winner #2: My favorite submission

- Winner #3: A randomly selected personal subscriber

Winners will receive a free handcrafted bobblehead of any person they choose, including themselves, each with an approximate value of $70. Every legitimate entry will increase your chances of winning, so get busy: Karate Kyle is waiting, and you don’t want to make him angry.

Update

Place a vote for your favorite submission below. Voting ends on April 16.

The contest is over. New submissions are welcome, but they will not be eligible for the prize.

The post The Best of Karate Kyle Contest appeared first on Martial Development.

An Idiot Travels to Shaolin Temple 1 Apr 2011 10:59 PM (14 years ago)

Karl Pilkington in An Idiot Abroad

The post An Idiot Travels to Shaolin Temple appeared first on Martial Development.